|

The Seed of an Idea

On December 16, 1959, Frank Horton wrote a letter to then-president of Old Salem Museums & Gardens, Charles B. Wade. After years serving as director of restoration for Old Salem and overseeing the revitalization and restoration of the historic Moravian town, Horton proposed an idea. He wrote:

The subject of the South’s history in this field has been greatly neglected by historians…. The South had a culture distinctive in many ways, principally brought by the rural economy of the area and its dependence, to a great extent, on England for manufactured goods. The … things produced in the South were often provincial in character, but is not this story worthy of the telling?[1]

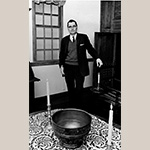

With this letter, Horton proposed the founding of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts. Horton and his mother, Theo Taliaferro, had been antiques dealers and collectors for many years in Clarkesville, Virginia, and Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and had assembled an impressive collection of southern antiques and material culture (Figure 1 and 2).

The Joseph Downs Challenge

One often-recounted turning point in the field of southern decorative arts occurred in 1949. You’ve no doubt heard the tale. At the inaugural Williamsburg Antiques Forum, then curator of the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Joseph Downs, made the remark that “little of artistic merit was made south of Baltimore.” Those were incendiary words to an audience that included southern collectors and scholars like Juliet Brewer who had provided Alice Winchester, editor of The Magazine Antiques, with the information for the 1947 issue that focused on Kentucky. That issue included an article by Kentucky collector, Eleanor Hume Offutt. Scholars debate whether it was Juliet Brewer or Eleanor Offutt who challenged Downs’s declaration. Whoever it was, she questioned whether Downs spoke out of prejudice or ignorance. To his credit, Downs pled ignorance, but the line in the sand had been drawn.

This now notorious exchange was the impetus for The Furniture of the Old South 1640-1820, the seminal 1952 exhibition jointly sponsored by Colonial Williamsburg, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and The Magazine Antiques. Although he had not attended that fateful Antiques Forum, Frank Horton heard about it and was happy to assist with the exhibition and to lend key pieces like the seventeenth-century Virginia court cupboard (Figure 3 and 4) he had acquired from the Brockwells, dealers who specialized in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century furniture and antiques. It may have been during this project that the idea for MESDA began percolating in earnest for Frank.

A Museum Takes Shape

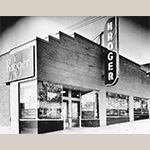

After 1952, he accelerated his efforts to collect interior woodwork from historic homes that were slated for demolition. Although Frank and Theo had always collected southern antiques, they began strategically refining their collection by culling objects from outside the South and actively seeking southern examples. Frank envisioned that he and his mother would follow in the footsteps of Henry Frances Dupont, the founder of Winterthur, and install the collected woodwork as architectural backdrops for the objects in a house he hoped to purchase for that purpose. When the logistics of that idea proved impractical, in 1960, Frank proposed constructing a new building to house the museum at the south end of Main Street in Old Salem. Fate had other plans, however. The Kroger grocery store (Figure 5) across the street from the proposed site on which Frank and his mother planned to build their museum became available.

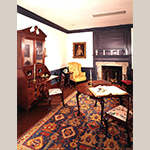

Within just a few short years, Frank and his mother paid to renovate the interior of the Kroger.[2] Period rooms took the place of freezer cases and bakery racks. Southern furniture replaced boxed and canned foodstuffs, and framed prints and paintings from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries hung where magazine racks and cash registers once stood. Two hundred and twenty-nine objects from Frank and Theo’s collection were carefully exhibited in ten meticulously installed period rooms. The museum opened on January 4, 1965, with a new facade and a completely transformed interior (Figure 6 and 7). Though she could not attend the opening due to a lingering illness, Mrs. Taliaferro noted in her diary that evening, “I am truly proud of my boy.”[3]

Collecting with Purpose

Today MESDA is widely recognized for its contributions to the study and understanding of southern history, decorative arts, and material culture. The museum is home to an ever-growing internationally renowned collection of southern decorative arts from Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama. The collection now numbers well over 3,600 southern objects exhibited in more than thirty gallery spaces, including three self-guided galleries (Figures 8-10).

Research at the Core

Always a stickler for the careful documentation of southern objects, people, and places, Horton was not content to just display southern treasures, however. In 1972 with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, he established a two-part research program designed to run parallel to the object collection program: the Field Research Program and the Craftsman Database.

The purpose of the Field Research Program was – and continues to be – to document southern decorative arts in private and public collections. These research files enhance our understanding of MESDA’s permanent collection and illuminate the breadth of southern material culture beyond what the museum can physically collect. The resulting field research files—both hard copies and digital—are “go to” resources used by collectors, scholars, and other researchers throughout the world who want to study southern material culture. Today, the resulting Object Database has approximately 20,000 files and continues to grow.

The Craftsman Database includes references to over 100,000 craftsmen and women in 127 trades working throughout the South. Their names were gathered through the careful reading of primary documents by MESDA researchers. This project continues to expand as more documents become digitally available. Together, these programs comprise the foundation of the MESDA Research Center.

In 1975, MESDA began publishing the Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts — also referred to as the MESDA Journal — as a vehicle to share the research gathered and assimilated through the Craftsman Database and the MESDA Field Research Program. Fifty years later, the MESDA Journal is a leading scholarly publication recognized for its dissemination of research related to southern history and material culture.

To further the study of southern people, places, and things, Frank established the Summer Institute in 1976. This month-long summer study program has, in its nearly fifty years, trained hundreds of scholars, students, and museum professionals in the study of southern decorative arts using MESDA’s resources to better understand what characterizes southern culture and objects. Additionally, MESDA is a favorite destination for collectors and scholars who attend conferences and programs held throughout each year.

A Sixty-Year Legacy

As MESDA celebrates its 60th year and the 50th anniversary of the MESDA Journal, it is safe to say that – yes, Frank – this is a story worthy of the telling. Thank you for being its founding author and providing generations of scholars the opportunity to contribute chapters to your legacy. By creating, collecting, and sharing objects, resources, publications, and programs that celebrate the distinct culture of the South, Frank Horton and his mother created not just a museum, they created a movement that continues to flourish.

Johanna M. Brown is Chief Curator and Director of Collections, Archaeology, and Research at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts. She can be reached at [email protected].

[1] Letter, Frank L. Horton, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, to Charles B. Wade, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, 16 December 1959. Letter filed in Administration Real Estate Files, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.

[2] The building was purchased for Old Salem Inc. by Mrs. Frank Forsyth.

[3] Theo Horton Taliaferro’s Diary, January 2, 1965, Frank Horton Collection, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.