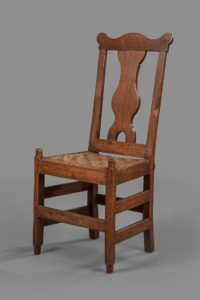

New Discoveries: Following Through: Zechariah Johnston’s Side Chair and its Commemorative Afterlives in Rockbridge County, Virginia

Ella Nowicki

In 1970, the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) acquired a walnut side chair (Figure 1) with a single-sentence provenance: “Original property of Zachariah Johnstone—brought by Zachariah Johnstone from Augusta Co., Virginia, to his new house, Providence Hill, in Stonebridge [sic] County near Lexington.”[1] This line is more than a lead for mapping the chair’s life onto Johnston’s biography. It suggests how, for decades, the chair has been understood as both a piece of eighteenth-century furniture and an object of memory, its meaning distilled into its association with a single prominent owner. Zechariah Johnston, as he more often spelled his name, was born to Scotch-Irish parents and was baptized in 1742 in Augusta County, Virginia.[2] Today he is best known as a Presbyterian advocate for religious freedom in the Virginia House of Delegates.[3] He is also remembered as a Revolutionary War militia captain and a decisive pro-Constitution voice at … Continued

2026 Editor’s Welcome

Kim May

This special issue of the MESDA Journal explores the American Founding through the objects people made, used, and remembered, and through the communities that gave those things meaning. The essays gathered here remind us that the Revolution unfolded in parlors and workshops, in taverns and studies, and within the intimate decisions of families and communities that navigated war, preserved traditions, and interpreted the world around them. Three full-length articles will anchor this year’s volume. Emelia Lehman’s study of James Read’s annotated copy of Reasons for Establishing the Colony of Georgia explores how a single book linked a Pennsylvania lawyer to transatlantic networks of print, intellectual exchange, and the hopeful—if fragile—dream of an American silk industry. Her close reading of Read’s marginalia, written on the eve of revolution, sheds light on northern interests in Georgia’s early silk experiments. Martha Hartley’s article turns to Wachovia, tracing how the Moravians in Salem, Bethabara, … Continued

New Discoveries: Paper Gardens: A Collection of Needlework Patterns Drawn by Lady Jean Skipwith

Emily Wells

For generations, a garden bloomed between the pages of a notebook. Opening its marbled paper covers reveals pages of mathematical exercises, as well as a collection of more than 600 floral needlework patterns drawn by Lady Jean Skipwith during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Born to Hugh and Jane Miller of Prince George County, Virginia, Jean spent much of her adolescence and young adulthood in Scotland. In 1788, she married her widowed brother-in-law, Sir Peyton Skipwith, and moved to Prestwould plantation in Mecklenburg County, Virginia.[1] The following year, she gave birth to her first daughter, Helen. As a girl, Helen used the notebook that would later house her mother’s needlework patterns to demonstrate her knowledge of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Once completed, its pages testified to her ability to manage household accounts, convert currencies, and calculate the weight of valuable goods. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation acquired the … Continued

Potters of the Yadkin Valley

Stephen C. Compton

Introduction Pottery collectors exploring North Carolina auctions, estate sales, and antique shops sometimes discover unsigned, lead-glazed earthenware pottery that has a perceived antiquity. Accompanying provenance is rare, and often the first assumption is that, if the vessel is not from Pennsylvania, then it is eighteenth- or early-nineteenth-century Moravian ware from North Carolina’s Bethabara or Salem potteries. However, recent research has shown that some of the earthenware formerly attributed to the Moravians was instead created by potters in Orange (now Alamance) County’s St. Asaph’s District, Quaker potters in Guilford and Randolph counties, Rowan County potters, and by Catawba Valley potters in Lincoln and Catawba counties who preceded that region’s alkaline-glazed stoneware makers.[1] This article argues that from the second half of the eighteenth century into the early years of the twentieth century, some largely unknown Yadkin Valley potters working in present-day Yadkin, Davie, and Wilkes counties, including Peter Myers, Seth Jones, … Continued

© 2026 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts