|

Introduction

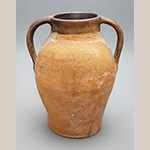

Pottery collectors exploring North Carolina auctions, estate sales, and antique shops sometimes discover unsigned, lead-glazed earthenware pottery that has a perceived antiquity. Accompanying provenance is rare, and often the first assumption is that, if the vessel is not from Pennsylvania, then it is eighteenth- or early-nineteenth-century Moravian ware from North Carolina’s Bethabara or Salem potteries. However, recent research has shown that some of the earthenware formerly attributed to the Moravians was instead created by potters in Orange (now Alamance) County’s St. Asaph’s District, Quaker potters in Guilford and Randolph counties, Rowan County potters, and by Catawba Valley potters in Lincoln and Catawba counties who preceded that region’s alkaline-glazed stoneware makers.[1]

This article argues that from the second half of the eighteenth century into the early years of the twentieth century, some largely unknown Yadkin Valley potters working in present-day Yadkin, Davie, and Wilkes counties, including Peter Myers, Seth Jones, Jacob Brewbaker, Alexander Hill, and others, may have made nothing but plain and slip-trailed decorated earthenware. More is known about the later work of some of these potters and the vessels they produced in southwestern Virginia, eastern and middle Tennessee, and elsewhere than about their lives and the work they produced during their time in North Carolina.

One key example is the Vestal family potters and others connected to them through marriage and training, who contributed significantly to pottery making in all three states. Some unattributed, or misattributed, earthenware pottery in private and museum collections, and likely more pieces yet to be found, undoubtedly originated in Yadkin Valley kilns run by the Vestal family and other potters working in the region.

This article introduces the names of important potters, identifies and describes two key kiln sites in the Yadkin Valley, demonstrates how to identify pottery produced in the Yadkin Valley, and examines the impact these potters and their work may have had on southwest Virginia and northeast Tennessee’s Great Wagon Road pottery-making tradition and beyond.

The Yadkin Valley

From the late eighteenth through the early twentieth century, North Carolina’s Yadkin-Pee Dee watershed – which encompasses much of the present-day counties of Cabarrus, Davidson, Davie, Forsyth, Randolph, Rowan, and Yadkin – was home to a network of potters, some of whom were connected through kinship and marriage. Most of these potters made earthenware pottery exclusively, and until now, their roles as early American artisans have gone largely unrecognized.

As was true of those who resided in the Cape Fear watershed – an area drained mainly by the Haw and Deep rivers and their tributaries – the Yadkin-Pee Dee watershed’s potters resided mainly in its northernmost counties. The explanation for this settlement pattern may be the same for both locations. The Pee Dee River originates as the Yadkin River in the Appalachian Mountains and the northwestern portion of North Carolina’s Piedmont region, and its water flows 435 miles to Winyah Bay, South Carolina. Waterborne trade along this river easily supplied the lower counties of the watershed but was less effective at outfitting those counties that were nearer the headwaters.[2] As a result, settlers in the northernmost regions relied more heavily on local craftsmen, including potters, to meet their needs.

Within this area, eighteenth-century settlers carved out homesteads, participated in commerce, and built communities in North Carolina’s rugged backcountry.[3] One important early community was Surry County (Figure 1). Created in 1771 from Rowan County, Surry County is situated at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains, bounded in the north by Virginia and by North Carolina’s Stokes, Yadkin, Wilkes, and Alleghany counties. Surry’s early history was shaped by the arrival of Quaker settlers, some of whose families had previously established homesteads in counties to the east in the Coastal Plain and Piedmont regions. Nearby Forsyth County, home to the Moravians’ large Wachovia tract and its Bethabara, Bethania, and Salem settlements, was formed from Stokes County through an earlier, larger version of Surry County. North Carolina’s Moravian potters have been well studied, and eight early Rowan County potters and their apprentices have been identified.[4] However, almost nothing is known about the Yadkin River Valley potters who lived and worked between the Moravians in Wachovia and potters active in Salisbury and Rowan County.

In Fisher’s River (North Carolina) Scenes and Characters (1859), Harden Taliaferro refers to Surry County in the 1820s as a poor man’s country, stating:

There is but little good land in it. All the valuable land lies on the small rivers and creeks, in very narrow bottoms. No rich man will ever be tempted to live there. But notwithstanding their long, cold winters and poor lands, the inhabitants, by hard labor and by the most rigid economy, live well. All extravagance, however, is necessarily excluded, and the people make the greater part of their own apparel, material and all. Money is very scarce, and corrupting fashions seldom reach them.[5]

“Yethen-ware,” he noted, was everywhere, an observation that clearly illustrates earthenware’s importance to Surry County’s pioneer families, who had few material possessions.[6] This sustained demand for locally produced pottery supported multiple generations of potters over the years.

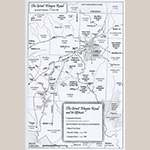

Among Surry County’s early potters were those who lived in and near Huntsville. Established in 1792 and situated near the west bank of the Yadkin River, close to its naturally shallow ford, Huntsville’s potters’ influence extended beyond the Yadkin Valley into North Carolina’s Catawba Valley, eastern and middle Tennessee, southwestern Virginia, and as far northwest as Illinois, Indiana, and Iowa. Of particular importance is the impact some of these potters may have had on the Great Wagon Road pottery tradition in southwestern Virginia and northeastern Tennessee.[7] This broad reach underscores Huntsville’s importance as a center for earthenware production and exchange.

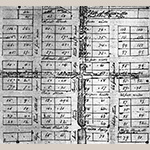

The Town of Huntsville

Few people today have heard of Huntsville, North Carolina, but as two mid-twentieth-century historians noted, a “hundred years ago Huntsville, just west of the Yadkin River on high rolling ground, was a thriving little village that had five general stores, a tobacco factory, two schools, a tavern, and several prosperous plantations” with large enslaved populations.[8] Huntsville was laid out in 1792 following its approval by the North Carolina General Assembly.[9] The town consisted of 111 half-acre lots bounded by streets that measured up to sixty-six feet wide (Figures 2 and 3). The town was strategically located along the path of the Great Wagon Road, a significant colonial and early American transportation route. From Philadelphia, the road ran to and through the Shenandoah Valley into present-day Stokes County, North Carolina, before traversing the Moravians’ Wachovia tract. From there, crossing the Yadkin’s shallow ford, it continued through Huntsville to Salisbury before extensions of the road led to states further south. One offshoot, the Georgia Road, branched off near Huntsville (Figure 4).[10]

Enslaved people’s labor contributed to the growth of the town and of several sizeable plantations near Huntsville. Tyre Glen (Tyree Glenn) built a large plantation at Enon along the Yadkin River and, with his partner Isaac Jarratt, actively participated in the slave trade. In 1860, Glenwood plantation encompassed 3,500 acres of Yadkin County land and included twenty-two slave dwellings, and Glen owned more land in Surry, Alleghany, and Stokes counties.[11] One hundred ninety-eight people were enslaved at Glenwood plantation, and Glen held additional enslaved women and men in other counties.[12] Although many of the area’s early residents were Quakers, slavery was a common practice in the area, and Glen’s participation in the slave trade was both supported and mirrored by other people in the region.[13]

Local memories of Huntsville reveal a vibrant community that supported various crafts. Before she died in 1963, Emma Long (ca. 1870-1963), whose father was physician and tavern owner Thomas Long, shared some of her memories and family lore about Huntsville:

Along about 1860, he [Thomas Long] was living in Huntsville again and was the operator of an immense tavern in the town. It had ever-so-many large rooms, and this was where the stagecoach stopped which traveled between Fayetteville and Wilkesboro every few days, and the passengers spent the night. My father also owned a whole drove of slaves which worked his land, and their cottages dotted the land around the plantation.

Then, and in the years that followed, his tavern and the ‘Red Store’ in Huntsville were popular meeting places for the entire surrounding country. Governor Zeb Vance stopped by the tavern, together with other distinguished persons. . . .[14]

As Long’s remembrances suggest, early Huntsville was a central hub of the region. The community had a post office, churches, merchants, wagon makers, blacksmiths, carpenters, masons, plasterers, and potters. With plenty of social activities and community events, Long recalled that “Huntsville was always a place for the people for miles around to congregate.”[15]

Huntsville’s growth and prosperity declined in the 1860s. The end of slavery and the United States’ defeat of the Confederacy in 1865 contributed to the town’s decline and, over time, to its near total disappearance. Seeking new land and even California gold, some residents moved on to western and midwestern locales. Today, little more than the so-called Potter’s Cabin (Figure 5), located on the town’s original Lot 15, offers a hint of the thriving town that once existed there.

The Potters

Peter Myers, Seth Jones, and members of the Vestal family made pottery in Surry County in the early decades of the nineteenth century. Part of a wave of early Quaker settlers, members of the Vestal family with Quaker roots had moved to Surry County from Chatham County, North Carolina, by 1790 and soon began making pottery there.[16] The Vestals may have been the first family to establish a pottery shop in Huntsville. The Vestals grew into one of the South’s most prolific and influential potting families, with the family producing at least seventeen potters bearing the Vestal name, as well as potters in the Wooton and Harris families who were related to the Vestals through marriage.

In 1850, Surry County was divided into northern and southern districts. The South Division consisted of the land south of the Yadkin River, which ran east to west across the county and south along its eastern border, bifurcating old Surry County into two distinct sections. Yadkin County was formed from Surry County’s South Division in 1850. In the 1850 US Census, the first to list a person’s occupation or trade, several potters of a similar age are listed as working in Surry County’s South Division, which included the town of Huntsville.[17] Potter Simon Bohannon was forty-one, Jacob Brewbaker was forty-six, Erasmus Hill was forty-five, and Thomas B. Naylor was forty; all resided in the vicinity of Huntsville. Potter William Alexander James worked a few miles south of Huntsville in Davie County, which was formed from a portion of Rowan County in 1836. A decade earlier, he lived in Surry County, perhaps in Huntsville, which is where he most likely learned his trade as a potter.[18] At least three generations of the James family extended the Huntsville pottery-making tradition into the first part of the twentieth century. Other nineteenth-century potters, like George A. Fraley, William C. Bird, Alexander Hill, Moses Ritchie, and William McQueen Welch, who later worked elsewhere in North Carolina and other states, also practiced their trade near Huntsville.

|

Approximate Working Dates |

|

|

1798 – 1810 |

|

|

1806 – 1810 |

|

|

1800 – 1880 |

|

|

1820 – 1881 |

|

|

1820 – 1920 |

|

|

1820 – 1939 |

|

|

1860 – 1880 |

|

|

1830 – 1869 |

|

|

1830 – 1859 |

|

|

1831 – 1850 |

|

|

1830 – 1860 |

|

|

1830 – 1851 |

|

|

1834 – 1860 |

|

|

1823 – 1860 |

Peter Myers

Peter Myers (b. ca. 1747) is identified as a potter and resident of Surry County in a deed written in 1800. This document shows that Myers sold Lot 10 in Huntsville to his wife Mary’s cousin Peter Eaton (b. ca. 1750), a minister, merchant, and land speculator.[19] Myers had purchased this property from Charles Hunt two years earlier on 14 December 1798.[20] Like most Huntsville lots, Lot 10 measured six by twelve poles (roughly 99′ x 198′), creating an area of seventy-two square poles (about half an acre).[21] If Myers set up and operated a pottery on Lot 10, it would have been for such a brief period (1798-1800) that the quantity of wares produced there would have been small.

While it is possible that Myers operated a pottery shop for a short period on Lot 10, it is more likely that his pottery operation was located outside of Huntsville, elsewhere in Surry County. One possible clue to the location of his pottery shop is a Surry County land entry by Abraham Creason from 1778 that describes his property’s location as being on the north side of the north fork of Deep Creek adjoining Jacob Feree and John Williams, including “the improvement whereon Peter Myers now lives for complement.”[22] In 1784 the State of North Carolina granted Peter Myers 160 acres on the north side of the north fork of Deep Creek. In addition to those lands, in 1779, he received a state grant for 350 acres on the east branch of Crooked Run Creek, which ran through a section of Surry County that became Stokes County after its formation in 1789. By 1800, Myers had sold all the property he is known to have owned except for one hundred acres of his 350-acre Stokes County Crooked Run tract.[23]

While the precise location of his pottery shop is still unknown, a Surry County bill of sale (Figure 6), dated 17 March 1800 and entered into court on 9 February 1802, from “Peter Myers (Potter) to Charles Hunt” further confirms Myers occupation as a potter.[24] Curiously, in this bill of sale, Myers sold Hunt some household furnishings along with “one potters glazing mill, [and] two potters turning wheels.”[25] It is unclear why Peter Myers sold some of his tools to Hunt; however, the fact that he was still identified as a potter when the sale was proved in court in 1802 suggests he had not abandoned the trade at the time of the sale. Myers appears in the 1810 census but not in the 1820 enumeration, suggesting that he died between those years.

Seth Jones

A court order dated 13 February 1806 confirms that Seth Jones was an active potter in Surry County, North Carolina. The document details the apprenticeship of sixteen-year-old Thomas Dillard, who was apprenticed to Jones “until he arrives to 21 years to learn the art & mystery of a Potter.”[26] The location of Jones’ residence in 1810 suggests that he lived near Huntsville, a conclusion supported by his presence in witnessing a deed in 1808, in which William and Sarah Howard conveyed two acres to the trustees of the Methodist Society to erect a “house or place of worship.” This small tract was the site for Huntsville’s Mt. Sinai Methodist Church.[27]

While Jones’ family lineage is not yet fully understood, some Jones family historians have identified a Welshman named Zachariah Jones (ca. 1735-1789) as likely being Seth’s father by his second wife, Sadie Vance, who had three sons named Seth, Jesse, and Robert.[28] Zachariah Jones left a bed and furniture for his granddaughter, Bersheba Jones in his will.[29] In 1817, a North Carolina resident named Zachariah Jones served as a bondsman for the marriage of Bethsheba (also spelled Bersheba and Bershaba in records) Jones to potter Silas Vestal.[30] Though inconclusive, this evidence suggests that Seth Jones may have had ties to Zachariah Jones’ family and may have known or worked for Vestal family potters.

The Vestal Family

Few American families rival the Vestals in terms of the sheer number of people from a single family who practiced the pottery trade. The family’s first potters most likely learned the trade from Quaker potters who established shops in North Carolina’s Piedmont region in the second half of the eighteenth century. Over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the family gave rise to nearly two dozen potters bearing the Vestal name, and through marriage, they are connected to many other potting families, including members of the Harris, Wooton, Naylor, and Brower families (Figure 7). The Vestal family can be traced through several key lineages, each of which significantly influenced pottery production well beyond the Yadkin Valley.

William and Elizabeth Messer Vestal’s Descendants

The first generation of North Carolina Vestals moved to Orange County in 1751 following the death of William Vestal Jr., a Frederick County, Virginia, iron bloomery operator.[31] Following William’s death in 1745, John Vestal took over his father’s share of the bloomery partnership and remained in Virginia. Moving south, William Vestal Jr.’s widow, Elizabeth, arrived in North Carolina in 1751 and settled on a Granville land grant tract located on the waters of the Rocky River with four of her sons, James, Thomas Curran, William III, and David Anthony, and her two daughters, Mary and Jemima.[32]

The Line of James Vestal Sr. (1730-1793)

James Vestal’s mother, Elizabeth, and his brothers William III and Thomas were received by the Quaker Cane Creek Monthly Meeting on 1 February 1751 by transfer from the Hopewell Monthly Meeting. While his mother and siblings were openly accepted into North Carolina’s Society of Friends, James had trouble complying with some of the rules. By December 1751, a complaint had been lodged with the Cane Creek Monthly Meeting against James Vestal for marrying outside the Society of Friends and drinking excessively.[33] That year, he married Mary Jay.[34] He later moved to Surry County and died there in 1793.

His son James Jr. (b.1767) may have been a potter since his sons Jay (b. 1808) and James Thomas (b. 1810) were potters. James Jr.’s daughter Sarah married potter Thomas B. Naylor, and his daughter Frances married potter John “Jehu” Wooton. John and Frances Wooton were the progenitors of seven known Wooton potters.

Jay Vestal reportedly worked as a potter in Washington County, Virginia, and Greene County, Tennessee.[35] Jay’s son Simon Sanford (b. 1830) was a potter, and Jay’s daughter Nancy married potter Alexander McEwen Harris. Their son Samuel J. Harris (b. 1853) was a potter.

Jay’s brother James Thomas was a potter working in Washington County, Virginia, where records from 1850 note that he had three men working in his pottery shop.[36] His son Jessee Vestal (b. 1828), the father of potter James Thomas (b. 1858), is well known for his flamboyantly autographed vessels, including a signed jug with a poem that reads:

long and lazy

little and loud

fair and foolish

dark and proud

a splendee branda jug

this is the 20th day of May 1849[37]

The Line of Thomas Curran Vestal (1727-1813)

Another significant line of Vestal potters began with William and Elizabeth Messer Vestal’s son Thomas Curran Vestal, who married Elizabeth Davis. Thomas and Elizabeth declared their intent to marry on 7 September 1754 before the Cane Creek Monthly Meeting and remained residents of Chatham County throughout their lives.[38] Thomas was a founding member of Guilford County’s New Garden Monthly Meeting, which was formed in 1754. His fellow New Garden members included Beesons, Mendenhalls, Hiatts, Hoggatts, and the brothers, Nathan, Zachariah, and Peter Dicks – all families associated with pottery manufacture.[39] If no Vestals were potters by this time, this was the opportune occasion for at least one, perhaps his son Jesse (b. 1772), to acquire the requisite skills for earthenware manufacture.

Jesse Vestal (1772-1855)

Thomas Curran and Elizabeth Davis Vestal’s son Jesse had at least three sons who became potters: Silas (b. 1799), Messer Amos (b. 1812), and Tilman A. (b. 1816). Another son, William (b. 1806), may have worked with his brother, Silas Vestal, in Greene County, Tennessee. Jesse may have established the Huntsville pottery shop that was supervised by his son Silas. Jesse’s wife, Sophia McDonald, died sometime after the birth of their son Tilman (b. ca. 1816). According to his son Asa, Jesse never remarried and spent the remainder of his life traveling from place to place.[40] Some evidence suggests that Jesse was associated with the Cain Pottery in Sullivan County, Tennessee, and may have traveled extensively as a journeyman potter for many years.[41] In 1840, Jesse Vestal lived alone in Davie County at a site south of Huntsville.[42] A decade later, in 1850, the seventy-seven-year-old Jesse resided in Surry County with his son Messer Amos Vestal, who at that time was listed as a merchant with real estate valued at $1,700.[43] Asa Vestal recorded that his father, Jesse, died in Chatham County in 1855 at age eighty-two.[44]

Silas Vestal (b. ca. 1799)

Silas Vestal, the eldest son of Jesse and Sophia McDonald Vestal and grandson of Thomas Curran and Elizabeth Davis Vestal, was working as a potter in Huntsville before relocating to Tennessee. Evidence of his occupation appears in the 1820 census, which records four people in his Huntsville household as mechanics.[45] This term was commonly used to identify artisans, handicraftsmen, and others engaged in skilled labor. Given his age, one of the men identified as a mechanic was Silas. Further confirmation comes from the diary of Huntsville potter William McQueen Welch, who recorded that he learned the pottery trade from Silas Vestal before moving to Wilkes County, North Carolina, in 1821 (see William McQueen Welch below).[46] Taken together, these records suggest that Vestal’s designation as a mechanic in 1820 referred specifically to his work as a potter.

Silas Vestal married Bethsheba Jones in Surry County, North Carolina, in 1817.[47] The following year, he purchased Lot 15 in Huntsville from Peter Clingman.[48] Lot 15 bordered High Street and appears to be the present-day site of the Chapman-Brewbaker log cabin (the Potter’s Cabin). Records indicate that by 1822, Silas owned two lots in Huntsville, acquiring the additional Lot 9 from William W. Chaffin.[49] Lot 9, situated on the corner of High and Pine streets, was just steps away from Vestal’s Lot 15 and was located adjacent to Lot 10, which was owned by potter Peter Myers between 1798 and 1800. In addition to his two lots in the town, in 1824, Silas Vestal owned 15 ½ acres adjoining Peter Clingman.[50] In 1825, the acreage was listed as having increased to 20 ½ acres.[51] It is possible that one of these properties was the site of his pottery operation. Lot 15 may hold particular significance because evidence of a pottery shop has been found nearby, including plain lead-glazed earthenware sherds, slip-trailed decorated wares, stub-stemmed smoking pipes, bricks, and kiln furniture. This evidence strongly suggests that Silas Vestal was an accomplished potter before departing Surry County for Tennessee.

Around 1825, Silas Vestal relocated to Greene County, Tennessee, and established a pottery there. In 1828, he purchased a ¾-acre site in Greene County, Tennessee, from potter William Stanley.[52] The high price paid for this small lot suggests that a pottery operation, or another significant improvement, may have already been located on the lot.[53] Further supporting the claim that the high price for this lot was because of its pottery operation, in 1830, Silas Vestal’s Greene County neighbors included John Harmon Sr., John Harmon Jr., Isaac Harmon, and Peter Harmon, who were all members of a prominent Tennessee pottery-making family.

In 1830, Silas Vestal’s household in Tennessee included an enslaved couple, whose ages were listed in census records as being between twenty-four and thirty-five, and their three children, all of whom were under the age of ten.[54] In his will, written in 1833, Silas Vestal declared that “slavery is inconsistent with justice” and made it his wish that Abraham and Sophia, and their now four children, Mahala, Margaret Ann, Henry, and Nervy, be freed following his death according to law.[55]

At the time of his death, Silas Vestal’s estate included “tools, a lead oven, and clay.”[56] His widow, Priscilla Ward Vestal, whom he married in 1826 after the death of his first wife, purchased much of his pottery-related equipment.[57] Silas’ sons, Isaac (b. 1822) and Caswell (b. 1826), are listed as potters in the 1850 census for Greene County, Tennessee, with William Stanley, who was likely a potter, living nearby.[58]

Messer Amos Vestal (1812-1886)

Jesse and Sophia McDonald Vestal’s son Messer Amos Vestal was an active Huntsville area resident, merchant, justice of the peace, and potter. On 9 February 1833, he married Rhoda Mendenhall, the daughter of Richard Mendenhall, a prominent Quaker and potter of Jamestown, Guilford County, North Carolina.[59] Messer Amos Vestal, and perhaps his father Jesse, may have worked as potters with Richard in Jamestown. This is supported by evidence of a kiln site near the Mendenhall plantation house in Jamestown, where at least one earthenware sherd (Figure 8) found at the site bears a partial inscription of the name Vestal, which could have been signed by either Jesse or Messer.[60]

Messer Amos and Rhoda moved to Surry County in 1835 and then to Maury County, Tennessee, around 1859.[61] Despite his considerable real estate possessions in 1850, Messer Amos Vestal’s apparent financial well-being did not last.[62] Possibly trying to get ahead of his financial troubles, on 10 April 1857 Messer sold Huntsville lots 5 and 22 to Thomas S. Martin.[63] However, by 19 December 1857, Samuel C. Welch and a long list of creditors filed a deed of trust securing Messer Amos Vestal’s indebtedness; he was given ten days to settle his accounts with lenders and creditors.[64] Having failed to satisfy his debts, all his real and personal property, previously offered as security, was put up for sale by trustee Samuel C. Welch on 15 January 1858. Slave trader Joseph A. Bitting was the winning bidder. George C. Mendenhall, Rhoda’s uncle, witnessed the deed conveying the Vestals’ property to Joseph Bitting.[65] Included in the sale were three tracts of land, including Messer Vestal’s residence. This eighty-eight-acre tract was in Yadkin County on the waters of Turners Creek, bordering land owned by Martin, Bitting, and Bohannon. Another fifty-seven-acre tract was situated near his residence on the road near the Methodist Mt. Sinai Meeting House. This land also bordered an “old field at the dividing corner with [potter] Moses Ritchie’s” land.[66] A third tract owned by Messer Amos Vestal, containing 24 ¾ acres, adjoined his second parcel and was bordered by the properties of Abraham Pruett and Sarah Dalton, the sister of potter William C. Bird. Vestal acquired the land in 1842 from the estate of Nathan Chaffin.[67]

While he mismanaged his finances, evidence unquestionably points to the fact that Messer Amos Vestal worked as a Yadkin County potter. In addition to his land and many personal property items, which were put into trust in 1857, Messer Amos Vestal’s possessions included “all the unburnt Potters wares on hand Supposed to be worth about $90.”[68] The presence of “unburnt” pottery among his possessions may have resulted from selling his pottery shop and kiln before the completion of the wares. It is unknown if his operation was located on one of his Huntsville lots or elsewhere on one of his nearby properties.

Excellent sleuthing by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh uncovered a letter from one of Messer Amos Vestal’s sons in which he identifies his father as a potter, further supporting the claim that he worked as a potter in Yadkin County.[69] Like his father, letter writer Tilghman Ross Vestal (b. 1844) worked as a potter, evidence of which emerged from documents relating to his conscription to serve in the Confederate Army. A Quaker, Tilghman Ross refused service and declined to pay the allowed $500 exemption fee due to his belief that to do so would aid in the war, which he opposed. As a result, he was imprisoned and tortured.[70] Impassioned pleading by some of his relatives led to his conditional release in 1864 to be “bound to work at the potter’s trade” for Quaker potter David Parr in Richmond, Virginia.[71] M. A. (Messer Amos) Vestal is listed as a potter in the 1870 census of Maury County, Tennessee. His household included the twenty-seven-year-old Tilghman Ross Vestal, who at that time identified himself as a teacher.[72]

Tilman A. Vestal (b. 1816)

Jesse and Sophia Vestal’s son Tilman A. Vestal was listed as a “stoneware manufacturer” in the 1870 census for Lauderdale County, Mississippi.[73] In 1880, he was referred to as a “wear maker.”[74] His son George Cyrus Vestal (b. 1851) is listed as a potter in the same census and likely worked alongside his father, Tilman.[75]

Furthering the Vestal pottery-making lineage, Tilman A.’s sister, Elizabeth, married Joshua Barker.[76] Their son, Samuel Vestal Barker (b. 1814), was a Guilford County potter. He married Elizabeth Caroline Jerrell, the sister of North Carolina potter Noah Cude Jerrell.[77] However, not all of Jesse Vestal’s children pursued pottery. Asa Vestal remained in Huntsville following his brother Silas’ move to Tennessee, working as a slave patroller during the 1820s.[78] By 1840, Asa had also left Surry County, moving first to Jackson, Missouri, and then around 1849 to San Jose in Santa Clara County, California, perhaps with hopes of finding gold. No evidence has been found to indicate he was a potter.

William Vestal’s (b. 1759) Descendants

Several descendants of William Vestal, son of Thomas Curran and Elizabeth Davis Vestal, were involved in the pottery trade. Wiley Vestal, William’s second great-grandson, lived with his cousin Messer Amos and his wife Rhoda Vestal in Maury County, Tennessee, in 1880 and may have worked in the Vestal pottery shop.[79] Wiley’s father, laborer George Washington Vestal, is listed immediately after Messer Amos Vestal in the 1880 census for Maury County, suggesting that he, too, may have been engaged in the pottery’s operation.[80]

Two additional descendants of William Vestal also worked as potters – his grandson John A. Vestal (b. 1818) and great-grandson Henry T. Vestal (b. 1838). John A. Vestal was the son of Thomas Vestal (b. 1791) and Mary Magdalene Brower.[81] He married Elizabeth Johnson in Chatham County in 1837.[82] His contemporary and first cousin, Alfred Moore Brower (b.1821), was also a potter and was most likely trained by the Fox family of potters. Brower’s sons, John Franklin (b. 1844) and James David Brower (b. 1851), both continued their father’s pottery-making tradition.[83]

William McQueen Welch

William McQueen Welch (1800-1881) (Figure 9), whose father was Huntsville’s John Welch and whose grandfather, David Welch, was one of Huntsville’s early residents, learned the pottery trade from Silas Vestal.[84] An account written by William Welch in 1876 describes his early life in North Carolina and his later travels. In this account he noted that “William Welch, the son of John Welch and Isabel McQueen, his wife who was a Scotch lady, was born January 1 1800 in a small village, Huntsville then Surry County, North Carolina. 3/4 of a mile West of the shallowford on the Yadkin River. In this village under Silas West [Vestal], as the Superintendent of pottery learned the trade.”[85]

Welch’s personal records note that he left Huntsville in 1821 for Wilkes County, North Carolina, where he established his first pottery near the Reddies River, a tributary of the Yadkin River.[86] While in Wilkes County, he married Elizabeth Judd on 29 May 1823.[87] Welch wrote a diary account describing his decision to leave North Carolina for Indiana in 1829:

I made a small farm and made a good living. But not learned in the ways of the world yet and trying to help or drag up everybody, I stood security and had to pay which took all my farm and some of my property to pay off the debt, which left me strapped, except a wagon, and three horses. This left me ready to emigrate to some new world or place for a new start. In the fall of 1829 I rolled out and landed in Richmond, Indiana.[88]

From Indiana, Welch moved to Mackinaw, Tazewell County, Illinois, where he recalled, “All of us liked to have starved to death.”[89] Driven away by the Black Hawk War, he and his family moved to Morgan County, Illinois, where they lived until 1836, when they once again set off for the Wisconsin Territory (later Iowa). In Van Buren County, a mile below Bonaparte, Welch set up the first pottery in the region. After that, his seemingly endless travels led him to Fairfield in Jefferson County, Iowa, where he set up another pottery shop. Welch’s next stop was Marion County, near Pella, Iowa, where he made stoneware (Figure 10). After selling his farm and the pottery he set up there, Welch made his final move to Coalport, where he established his last pottery.[90]

Excavations show that Welch’s Coalport kiln was “a circular to ovate dome-shaped building with several smoke stacks 1 ½ feet high and dimensions of 14 feet wide and 24 feet long,” and its fire boxes were “2 feet wide and 2 ½ feet deep.”[91] Welch’s Coalport kiln may have resembled those he encountered during his time in North Carolina or others he saw elsewhere in his travels.

The Wooton Family

The Vestal family was a dominant force in early southern pottery traditions, and their reach extended beyond the immediate family. In the 1830s, the Vestal legacy made its way to Washington County, Virginia, where John Wooton, formerly of Surry County, North Carolina, established a pottery.[92] In 1820, John Wooton (aka Jehu T. Wooten; b. ca. 1803 in Iredell Co., North Carolina) married Frances Vestal, James Vestal Jr.’s daughter.[93] It seems likely that John learned the trade from the Vestals. Following Frances’ death, John married Mary Jane Harris in 1865, and on their marriage record, he identified his parents as Thomas and Elizabeth Wooton and listed his occupation as a potter.[94] In 1810, John’s father, Thomas Wooton, resided a few houses away from Neal Bohannon and James Vestal Jr., placing the three pottery-related families geographically near one another in old Surry County at a very early period.[95]

Census records indicate that John and Frances Wooton moved to Virginia in the early 1830s. In the 1830 census, John and his household are still listed as residing in Surry County, North Carolina; however, in 1850, his seventeen-year-old daughter Nancy was recorded as being born in Virginia, indicating the family moved to Virginia between 1830 and 1833.[96] The 1840 census for Washington County records that one person in John Wooton’s household was “employed in manufactures and trades,” which suggests that he was working as a potter soon after he arrived in Virginia.[97] By the 1850 census, his occupation is listed as a potter.[98] His son, James Wooton (b. 1828), aged twenty-two, born in North Carolina, is likewise called a potter and lived in the household next to his father’s with his wife Charity Harris Vestal and their two children.[99] John Wooton’s second son, John T. Wooton (b. ca. 1840), was a potter, as was his son, Thomas C. Wooton (b. ca. 1870).[100]

At least three of James and Charity Wooton’s sons were potters or pottery workers: James Alexander (b. ca. 1851), Jehu Raymond (b. 1851), and William T. (b. ca. 1866).[101] In 1880, James Alexander was a thirty-year-old potter in Washington County, Virginia; his fourteen-year-old brother William T. Wooton resided in his household and was listed as a pottery worker.[102] Records suggest that James Alexander’s son, Josephus J. Wooton (b. ca. 1874), also joined the family pottery business.[103] In 1880, James’ brother, Jehu Raymond, a farm laborer at the time, lived nearby. Other potters in the region included John B. McGee, his son Fred H. McGee, Sam Harris, and J. M. Barlow.[104] In the last years of his life, Jehu Raymond Wooton resided in Hamburg, Iowa, where the 1920 census lists him as a potter.[105]

In addition to the ties by marriage between the Wootons and the Vestals, the families also intersected in commercial ways, forming a large network of potters. In 1850, Nancy M. ‘Ann’ Vestal (daughter of Surry County-born potter Jay Vestal [b. ca. 1808] and Hannah Johnson and granddaughter of James Vestal Jr.) married Alexander McEwen Harris (b. 25 February 1825).[106] Harris was a potter who, along with his son Samuel Jay Harris (b. 8 May 1853), probably worked in the Wooton Pottery. Nancy Vestal Harris’ brother, Simon Sanford Vestal, was also a potter.[107] Simon Sanford was born in Virginia about 1830 and, in 1860, was recorded as being a Washington County, Virginia, potter. Twenty-year-old potter J. T. Wooton lived next to him at the time.[108]

The James Family

In his 1901 Masonic picnic address, David Moffatt Furches, chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, recalled the wave of migration that reshaped Rowan County (later Davie County) around 1800. Families from Currituck County — including the Brickhouses, Ferebees, Brocks, Taylors, and others — settled near Farmington (Figure 11), a region still remembered in his youth as “Little Currituck.”[109] Among the arriving families were the Jameses, who were of purported Welsh descent and had migrated from Bucks County, Pennsylvania, through Currituck before establishing themselves in Rowan County. Their community, known as Jamestown, lay just north of Farmington and a few miles south of Huntsville.[110]

Samuel James (1760–1848) appears in the 1810 and 1830 Rowan County censuses with his wife, Elizabeth Cornell.[111] Their son Cornell James (1790s–c.1840) married Nancy Brickhouse in 1812 and initially settled near Farmington on Huntsville Road.[112] Census records show that by 1820 Cornell had moved to Surry County (later Yadkin County), likely in the Huntsville area, where he was “engaged in manufactures,” a designation that may indicate pottery production.[113] He later returned to Rowan County, but his life ended violently in Huntsville before 1840. According to his grandson William Franklin James, he was killed while carousing with friends when one of them hit him in the head with a rock.[114] A widowed Nancy James was head of household in Davie County in 1840.[115]

Cornell and Nancy’s son, William Alexander James (b. ca. 1819), was involved in the pottery trade.[116] His son, William Franklin James, recalled that his father, William Alexander, learned to make pottery sometime between 1830 and 1840, although who taught him the trade remains unknown.[117] If he was not trained by his father, Cornell James, he was most likely tutored by one of several potters active in and around Huntsville between 1830 and 1840. For example, in 1840, potters Erasmus Hill and Jacob Brewbaker were “employed in manufacture and trade” and either could have trained him.[118] In 1870, William Alexander identified himself as a potter living in Davie County’s Farmington Township, but by 1880, widowed and living with his son Julius, he described himself as a “huckster,” suggesting he had abandoned the craft.[119]

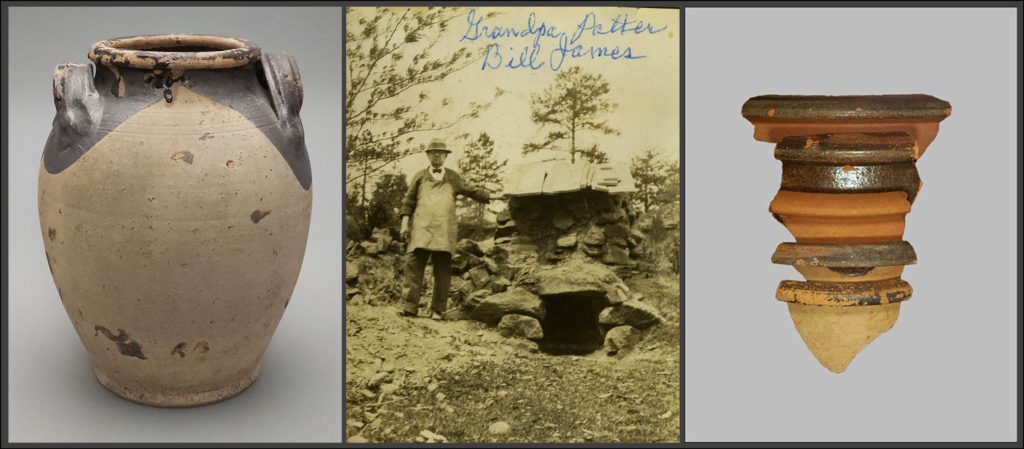

William Alexander’s son, John Henry James (b. 1847) worked, at least briefly, in the pottery trade before turning to mercantile pursuits.[120] While little is known about John Henry, much more is known about William Franklin James (1851–1939), the third-born son of William Alexander and Mary Sizemore James. William Franklin’s commitment to the craft ensured that the James family pottery legacy persisted into the twentieth century.

Known colloquially as “Potter Bill,” William Franklin James was remembered as much for his large personality as for his craft. Locals recalled the great pride he took in his horses, his lively presence at social functions, and his, at times, troublesome courtships.[121] When she was interviewed in 1995, ninety-year-old Davie County resident Bertice Smith said, “He [Bill] must have been a widower. He went to box suppers and picked out somebody he liked. One time he got in my box and said, ‘When it’s time to go home, I have my chauffeur out here and I’ll take you home.’ He got to be a bother.”[122] On another occasion, Bill was horse-whipped by some men for annoying a school teacher.[123] Potter Bill’s granddaughter wrote in explanation that “Being a foolish old widower, he was enticed to attend all functions where he would spend his money, and the said school marm accepted a string of pearls from him, a fact which I suppose he thought gave him the privilege to ‘annoy’ her.”[124]

Beyond his colorful character, Bill was celebrated and remembered in the community for his pottery production. He claimed to have learned the trade from his father; however, other accounts provide conflicting information about who actually trained him.[125] Bertice Smith claimed that a Moravian potter taught William Franklin James, while others referred to him as the “last Moravian potter,” further supporting that claim.[126] While William James’ claim that his father taught him the craft refutes this notion, accounts like Bertice Smith’s often possess a kernel of truth and should not be wholly discounted. It is plausible that William, already trained by his father, also gained experience in Salem as a journeyman potter with either Heinrich Schaffner (1798-1877) or Daniel T. Krause (1836-1903), whose shops remained active in the late nineteenth century (Figure 12). However, James’ updraft kiln, seen in Figure 13, differs from the Schaffner-Krause cross-draft kiln. If he did work as a journeyman in Salem, he evidently did not adopt its form upon returning to Davie County.

The James pottery site was located at Jamestown, an unincorporated area north of Farmington, along the road to Huntsville where the James families lived. Bill James and his grandson, James Ray Graham (1912-1985), made molded, stub-stemmed pipeheads on the site.[127] Many were sold to the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company to be included with pouches of smoking tobacco.[128] Farmington resident J. D. Furches (b. 1922) recalled that as a youth, he had set clay pots from the pottery on fence posts and shot them with a slingshot.[129] Another local resident, Ed Johnson, remembered picking up broken pipe fragments from around the old kiln.[130]

Oral tradition describes the kiln as tall, made of brick or stone, with a cave-like pit near the kiln that ran underneath the roadbed adjacent to the pottery.[131] A surviving photograph of William F. James (Figure 13) standing beside his kiln confirms its exterior was built of stone. From its appearance in the photograph and from recollections of those who saw it, the kiln was most likely a square or rectangular updraft-type kiln, perhaps similar to those used by some Quaker potters in Randolph and Guilford counties. Figure 14 illustrates a cross-section of how a Guilford County kiln operated by David Hockett might have looked, which may well represent the basic design of the James kiln.[132]

Some earthenware kilns used by potters in Greene County, Tennessee, may have resembled the James kiln. A kiln used by the Click family was described as “built round like an Eskimo hut with one door and a small hole in the top.”[133] The kiln utilized by William Thomas Bohannon, the son of Simon Bohannon, who produced wares in the vicinity of Huntsville, in Surry County, North Carolina, and Greene County, Tennessee, was described by his son John Bohannon as being “an air tight building shaped like an Eskimo snow house with one door.”[134] These kilns most likely functioned as updraft kilns.

James likely got his clay from two sources – one on the backside of a dairy farm located on the west side of the road that runs from Farmington to Huntsville, and the other along Turners Creek, a tributary of the Yadkin River, north of the pottery site. Farmington resident Wilburn Spillman described this clay pit as “a hole as large as a barn.”[135] This pit may have been a clay source for other potteries near Huntsville and Farmington.[136] Spillman also noted that Bill James had several wagons that he used to sell his wares “all over the state.”[137] A man named Alonzo Langley, who was the great-grandson of Huntsville-area potter Jacob Brewbaker Jr., rode with him on his trips.[138] Although it is unlikely that the wagoners traveled too far from Davie County, signed pottery from the James kiln, such as a lidded and painted sugar jar (Figures 15-16) found near Fancy Gap, Virginia, attests to the far-flung disbursement of the wares.

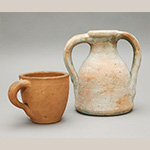

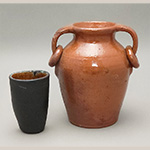

At a time when most potters in North Carolina had shifted from earthenware to stoneware production, Bill James continued to produce earthenware pottery. His lead-based glazes appear to be tinted with iron or manganese or no colorant, which produced a clear glaze. Examples attributed to him (Figures 17-20) demonstrate a sparing, primarily utilitarian purpose for his use of glaze.

It is likely that Bill James’ work and wares made by his brother John Henry James resemble the work of their father, William Alexander James, and possibly that of the master potter from whom he learned the trade. If not by Bill James, the large jar in Figure 21 is likely the product of his father or another turner in the Huntsville area. The vessels (Figure 22) with handles that are directly attached to the rims, examples of which are found in the Yadkin-Davie County region, may represent a distinctive characteristic of the James family’s work. Unlike most North Carolina strap handles, which tend to be shaped like a comma and are attached below the rims of jars and other wares, James’ handles (Figure 23) are directly attached to the rims of his vessels, extending from the rim before turning down to connect to the side of the piece. This technique serves as a signature of Bill James’ work and is an essential diagnostic trait in identifying his pottery.[139]

In the 1920s and 1930s, prior to his death in 1939, Bill James produced some wares meant to be painted on their exteriors. Vessels from this period, such as those in Figures 24-27, exhibit colorful splashes of paint, annular bands of color, and intricately lined flowers and vines. Perhaps influenced by the Arts and Crafts Movement, Bill may have found a ready market for these decorative, hand-crafted, hand-painted wares in and around Winston-Salem, Mocksville, and Salisbury, as much of this painted pottery has been found there. Bill likely did not paint the pottery himself. In the 1920s, he employed at least two women in his community to paint pottery – Mattie Bahnson and Bertha Johnson.[140] Between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Hiltons, Browns, Penlands, and Kennedys, among other potters from western North Carolina, chose to leave the exterior surfaces of their wares unglazed, allowing their owners to decorate them.

Earthenware pottery production in North Carolina declined after the first half of the nineteenth century. Much of the earthenware pottery made by North Carolina potters after 1850 consisted of shallow-walled pans known as “dirt dishes,” which were designed for baking in home ovens, and flowerpots.[141] However, Bill James’ palette of wares included lidded sugar jars, bowls, cups, chambersticks, large and small storage crocks, rundlets, wall pockets, jugs, and two-handled jars with donut-shaped toruses hanging from their handles (Figure 28). He also created presentation pieces (Figures 29-30) bearing a person’s name and his signature. At least one piece of ware that has been collected was signed by William F. James, with both Farmington and Winston-Salem locations inscribed into the clay.[142]

A glimpse of Bill James’ skill and production can be seen in a 1927 Twin City Sentinel newspaper article describing a demonstration at a Winston-Salem high school that Bill did late in his career. He astonished students with his speed and skill, producing a flower bowl, vase, jug, and small barrel. He claimed that “there is a ready market to pottery of all sorts; and that with his wheel, he can make on an average of 200 small articles a day.”[143]

Bill James’ work may uniquely link North Carolina’s eighteenth- and nineteenth-century earthenware tradition to the critical early twentieth-century transitional period when North Carolina’s utilitarian potters began making art wares for home decoration and display. His anachronistic forms and finishes may hint at the wares produced by his father, his father’s mentor, who may have been Potter Bill’s grandfather, Cornell, and even potters who worked before the Jameses in Surry (present-day Yadkin) County’s Huntsville community.

George A. Fraley

George A. Fraley (1813 – ca. 1892), a Davie County resident until around 1857, appears to have been involved in pottery production in White County, Tennessee, from the 1860s to the 1880s. He was born in Davidson County and lived in Rowan County (later Davie County after 1836) before moving to Tennessee sometime around 1857. It is unknown if William Alexander James or another area potter was responsible for his training; however, the fact that he was around forty-four years old when he left North Carolina for Tennessee suggests that he may have gained his skills while living in Davie County. This makes it possible that he learned from William Alexander James or another potter in the vicinity of Huntsville in Yadkin County.[144] Land records show that, soon after moving to Tennessee, Fraley purchased property containing a pottery shop from potter Henry Collier. Tennessee archaeologists Samuel D. Smith and Stephen T. Rogers note that Fraley “owned and remained involved with a pottery most of his life.”[145]

Simon Bohannon

The Bohannon family’s North Carolina roots trace to Duncan Bohannon (b. 1704), who settled along the Rocky River in Orange County (present Chatham County), North Carolina. His property was located near the lands occupied by potting families including the Landrums, Rhodes, and Drakes before these families moved to South Carolina’s Edgefield District.[146] Duncan’s son John (1729-1789) moved to Surry County, marrying Sarah Cassady (Casada) there on 19 November 1781.[147] Their son Neal Bohannon married Ann Hadley in Surry County in 1805, and they were the parents of Simon Bohannon (b. 1808), who worked as a potter in Surry County.[148]

Potter Simon Bohannon first appeared as a head of household in the 1830 census for Surry County when he was about twenty-one years old.[149] While Simon’s occupation in 1830 and the details of his training as a potter are unknown, a court case brought against him in 1835 provides evidence of his association with another Surry County potter. In this case a Jonesville merchant, Nathan Moffit & Co., brought a suit against Bohannon. Potter William C. Bird acted as surety on behalf of Simon Bohannon, but court minutes state that “The security William C. Bird surrendered the (defendant) Simon Bohannon in discharge of [himself] in open court & ordered into custody of [sheriff].”[150] Neither the cause nor the outcome of this case is apparent; however, the association between William Bird and Simon Bohannon could suggest a shared interest in the same trade. That Simon was engaged in potting by 1840 is supported by the census, in which one person in his family is recorded as being “employed in manufacture and trade.”[151] By 1850, Simon’s occupation is clearly identified in the census as a potter. He is listed with his wife, Eda Greer (also known as Edie), and their eight children, ranging in age from one to eighteen (Figure 31).[152]

Simon Bohannon moved from Yadkin (formerly Surry) County to Greene County, Tennessee, where he next appears in the 1860 census as a potter.[153] Bohannon family lore states that he traveled to Tennessee with a donkey laden with pottery, selling his wares along the way.[154] His relocation from North Carolina to Tennessee likely occurred between 1850, when he was listed as a potter in Surry County, and 1854, when his daughter, Mary C. Bohannon, married Rufus Lucky, a potter in Greene County.[155] In 1850, Lucky lived with potter Isaac Vestal, son of Silas Vestal, formerly of Huntsville. Isaac’s brother, potter Caswell Vestal, was bondsman for the marriage.[156]

After establishing himself in Greene County, Simon Bohannon may have joined J. A. Lowe and William Hinshaw in completing a load of pottery started by Christopher Alexander Haun, a potter from Greene County, Tennessee. In 1861, while awaiting sentencing for burning a Greene County bridge to prevent its use by Confederates, Haun wrote a letter to his wife asking that “Bohannon, Hinshaw, or Low[e]” finish a load of ware.[157] Whether any of the three potters completed Haun’s unfinished ware is not known, but the fact that Haun, an accomplished potter, asked that Bohannon finish his wares suggests that Bohannon was quite a skillful potter himself.

Simon Bohannon died in Greene County, Tennessee, in 1869 and is buried in the New Bethel Church Cemetery (Figure 32). His family remained in Greene County after his death. In 1870, widowed Eda Bohannon headed her household in Greene County.[158] In the 1880 census, Simon’s forty-two-year-old son William Thomas Bohannon (Figure 33) is listed as a farmer and potter. His other son Pleasant Lycurgus (“Larcurk”) Bohannon, lived with his brother William, but his occupation is not identified.[159] William Thomas Bohannon married Martha Jane Harmon, the daughter of Sparling B. and Catherine Carter Harmon.[160]

William C. Bird

Born around 1788 – possibly in Maryland, though later records alternately list North Carolina – William C. Bird was the son of Joseph and Ann Bird, who had settled in Surry County, North Carolina, by 1800.[161] Documentary evidence of Bird’s own work as a potter is scant, yet circumstantial records suggest his involvement in the craft from an early date. His young adulthood is documented in War of 1812 service records that note his enlistment in the Tennessee Volunteers under Colonel Benton, marching to Natchez and Talladega before his discharge in 1813.[162]

By the 1820s, Bird had returned to Surry County, where he served as guardian to his widowed sister Sarah Dalton’s children and frequently appeared in proceedings for the estate of her husband, Jonathan Dalton.[163] In 1828 he was among several Huntsville citizens promoting Andrew Jackson’s presidential candidacy, but the following year his name appeared in a far more sensational context: an estrangement from his wife Rebecca and a criminal case culminating in his conviction for manslaughter in the death of a man named Andrew McCollum, who, according to contemporary newspaper accounts, had “seduced and torn from his affections and his home” Bird’s wife.[164] Court minutes record that Bird claimed benefit of clergy and was fined $20, a lenient sentence suggesting the court accepted the mitigating circumstances.[165]

Bird remained in Surry County into the 1830s, serving as security for potter Simon Bohannon in 1835, a telling association that strengthens his identification with the trade.[166] His father’s 1832 will had left him seven enslaved people and the house, barn, tanyard, and orchard where he then lived.[167] By 1836, Bird had relocated westward to Hardeman County, Tennessee, where tax and deed records document his ownership of 192 acres, later identified archaeologically by Samuel D. Smith and Stephen T. Rogers as the site of a nineteenth-century pottery operated by William C. Bird himself.[168] His association with Simon Bohannon in North Carolina and the fact that he opened a pottery shop soon after moving to Tennessee suggest that he was already a skilled potter when he arrived in Hardeman County.

By 1850, Bird and his sons moved to Arkansas, where he identified himself as a farmer. His sons William and Nathaniel were potters and resided nearby.[169] He remained in Arkansas through at least 1859, but by 1870, he had returned to Yadkin County, North Carolina, where he was recorded in the household of his sister Sarah Dalton.[170] In his 1871 War of 1812 pension application, Bird gave his residence as “Huntsville in the family with his sister Mrs. Sarah Dalton.”[171] He died on 3 February 1876 and was remembered in The Weekly Sentinel as “William Bird, of Yadkin county, a veteran of the War of 1812.”[172] His long and peripatetic life, spanning North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas, traces the broader migration of southern pottery traditions across the early American frontier, even if the surviving evidence of his direct handiwork remains fragmentary.

Thomas Benjamin Naylor

Thomas B. Naylor (b. ca. 1809/10) is listed as a potter in the 1850 census for Surry County.[173] Born to Benjamin Naylor and Mary W. Rhodes in Albemarle County, Virginia, the family moved to Surry County, North Carolina, soon after Thomas was born.[174] Thomas married Sarah Vestal, daughter of James Vestal Jr, in Surry County on 17 October 1831.[175] Sometime between 1850 and 1860, Thomas and Sarah moved from Surry County to Washington Township, Poweshiek County, Iowa, where they are listed in the 1860 census.[176] It is unknown if Thomas Naylor worked as a potter after leaving North Carolina.[177]

Jacob Brewbaker

In 1850, forty-six-year-old Jacob Brewbaker (Brubaker) was working as a Surry County potter.[178] Born in South Carolina around 1803, his father Jacob Brewbaker Sr. (b. ca. 1765) relocated the family from Fairfield County, South Carolina, to the Huntsville area of Surry County, North Carolina, sometime between 1803 and 1810.[179] Jacob Jr.’s parents may have lived with him when the census was taken in 1830.[180] He married Cynthia Hall in Surry County on 27 February 1833, with potter Moses Ritchie serving as the marriage bondsman.[181]

In the 1840 census, one person was “employed in manufactures and trades” in Jacob Brewbaker Jr.’s household.[182] In 1850, potter Jacob Brewbaker Jr. lived six households away from merchant (and potter) Messer Amos Vestal.[183] Jacob Brewbaker continued his trade at least through 1860, where he remained listed as a potter in that year’s census.[184] He is identified as a farmer in the subsequent censuses of 1870 and 1880, and it is unknown if he also continued to make pottery.[185] According to his tombstone, Jacob Brewbaker died at the age of 92, and he and his wife, Cynthia, are buried in Yadkin County’s old Mt. Sinai Methodist Cemetery along with other Brewbaker family members.[186]

Erasmus Hill

Potter Erasmus Hill (ca. 1808-1851) first appears in the 1830 census in Surry County.[187] He is listed two households away from Asa Vestal, whose brothers Silas, Tilman, and Messer Amos Vestal were – or would become – potters. Eight names below that of Erasmus Hill, potter Moses Ritchie’s name is recorded next to the name of blacksmith Isaac Brewbaker, brother of potter Jacob Brewbaker Jr.[188]

In 1840, one person in Erasmus Hill’s household was “employed in manufacture and trade,” suggesting he may have been involved in pottery production by this date. Potter Jacob Brewbaker and Catherine, Jacob Brewbaker Sr.’s widow, lived nearby, as did potter William A. James.[189]

In 1850, forty-five-year-old potter Erasmus Hill and his wife Sarah still lived near potter Jacob Brewbaker.[190] By the next year, however, an entry dated 8 November 1851 in The People’s Press, a newspaper published in Salem, North Carolina, noted the death of “Mr. Erasmus Hill, aged 40 years,” of Yadkin County, “on the 1st instant.”[191] After his death, connections between these potting families continued, with his daughter Susan Hill (b. 1830) marrying into the Brewbaker family. She married blacksmith Washington Brewbaker (b. ca. 1828), the son of Isaac and Elizabeth Dixon Brewbaker. The wedding was conducted on 11 September 1853 by potter and Justice of the Peace Messer Amos Vestal.[192] Pottery-making Hill, Brewbaker, Vestal, Ritchie, and James families were neighbors and perhaps allies in the trade.

Alexander Hill

Following a run-in with the law in 1836, Surry County-born Alexander Hill (1812-1860) moved to Cabarrus County sometime between 1836 and 1838. He and fellow potter Moses Ritchie were indicted and convicted in Surry County on 1 March 1834 for unlawfully playing cards with two enslaved men – an act prohibited by state law. Court records outlined their offense:

The jurors for the state upon their oath present, that Moses Ritchie and Alexander Hill, both late of said county, and both white men, on March 1, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and thirty-four, with force and arms, in said county, unlawfully did play at a game of cards with two slaves, viz. John, the property of one Peter Clingman, and Juan; contrary to the statute in such case made and provided, and against the peace and dignity of the state. A motion in arrest of judgment was submitted by the counsel for the defendants; which being overruled, and judgment pronounced, the defendant, Ritchie, appealed.[193]

An 1830 North Carolina law made it illegal “for any white person, free negro, or mulatto, to play at any game of cards, dice, ninepins, or any game of chance or hazard, whether for money, liquor, or any kind of property, or not, with any slave or slaves; and any white person, so offending, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.”[194] This statute criminalized certain interracial social interactions with enslaved individuals, with a penalty of either a fine or imprisonment “not [to] exceed six months.”[195] While Moses Ritchie challenged the ruling of the court by appealing the case, perhaps Alexander Hill thought it better to move out of the county.

In Cabarrus County, Hill worked as both a farmer and potter.[196] One of his close neighbors was potter Michael Goodman (b. 1824), whose brothers John (b. 1822) and Tobias (b. 1828) were also potters.[197] John Goodman was the son-in-law of, and worked with, noted Catawba Valley potter Daniel Seagle in Vale, North Carolina.[198] In 1838, Alexander Hill married Eleanor Ritchie in Cabarrus County.[199]

Moses Ritchie

Moses Ritchie (Ritchey) was born to Henry Ritchie and Eva Magdalena Fesperman in Cabarrus County, North Carolina, on 22 June 1798 and was christened at St. John’s Lutheran Church (Dutch Buffalo Creek Church) on 23 September 1798.[200] When Moses learned the pottery trade and from whom is not known. His cousin Paul Ritchie (b. 1810; son of Michael Ritchie and Elizabeth Ann Walker) was also a potter, and the two were likely among the first members of the family to engage in the craft.[201] Their descendants include at least sixteen potters, including Moses’ sons Henry, Thomas, and Joseph, and Paul’s sons George Pinkney and William M. Ritchie. Ritchie family potters are best known for alkaline-glazed stoneware made in Lincoln and Catawba counties.[202]

Although Moses’ training as a potter is not yet fully understood, it is possible that he learned the trade in Cabarrus County. In 1764, his grandparents Hans Jacob and Maria Catharina Meyer Rüetschi purchased 254 acres in Mecklenburg County (later Cabarrus County) on both sides of Dutch Buffalo Creek from Governor Arthur and Justina Dobbs.[203] The area around Dutch Buffalo Creek, which runs near the boundary of Rowan and Cabarrus counties, near the Lutheran Organ Church, was home to several potters. Among them was Henry (Johann Heinrich) Wenzel (1734-1797), who trained his stepson, Benedict Mull (Moll; 1777-1857).[204] Another nearby potter, Thomas Pasinger (1765-?), a former apprentice of Moravian potter Henry (Johann Heinrich) Beroth’s, moved from Salisbury in Rowan County to a portion of Mecklenburg County that became Cabarrus County in 1792.[205] Pasinger settled not far from the site of the Ritchie family lands. He worked as a potter until at least 1824.[206] Given their geographical proximity, Ritchie may have acquired his pottery-making skills from Mull, Pasinger, or another nearby potter. If so, he probably learned earthenware production before adding stoneware manufacture to his skill set.

Ritchie may have been drawn away from Cabarrus County to Surry County’s town of Huntsville to work as a journeyman for Silas Vestal’s (or another potter’s) earthenware pottery shop. His presumed apprenticeship may have ended when he attained his twenty-first birthday in 1819, setting him free to pursue work elsewhere. On 15 November 1823, Moses Ritchie married Susannah Hill in Surry County, placing him in the county by 1823 and tying him to the Hill family potters.[207] Before she died in 1832, Susannah gave birth to four sons: William Monroe (1821-1828), Henry (b. 1822), Thomas (b. 1825), and Joseph (b. ca. 1829).[208]

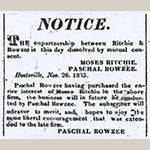

Several Surry County incidents suggest that Moses Ritchie remained in Huntsville following young Susannah’s untimely 1832 death. On 10 February 1834, a notice in Salisbury, North Carolina’s Journal newspaper (Figure 34) announced the 26 November 1833 dissolution of a Huntsville partnership between Ritchie and Paschal Rowzee.[209] The purpose of this business is not stated. Rowzee remained in Surry County through 1840 before moving to Bedford County, Tennessee, by 1850, where he identified himself as a carpenter.[210]

In addition to properties outside Huntsville, Moses Ritchie purchased at least five lots within the town’s boundary (Lots 6, 7, 4, 20, and 23). In 1834, Ritchie sold all his town lots to Thomas C. Davis; he may have been preparing to move away from Surry County and Huntsville.[211]

In 1928, John Johnson (a relative of potters Eli, Harvey M., and J. D. Johnson) of Vale, in Lincoln County, recalled, “I now being 87 years old, the first I remember about the pottery business in this section was when Moses Ritchie run a jug factory about 75 or 80 years ago, and he had three sons, Thomas, Henry and Joseph, who engaged in pottery after their father died, and one of these is running it extensively now.”[212]

Johnson’s account suggests that Moses Ritchie operated a shop near Lincoln and Catawba counties as early as 1848. His whereabouts between about 1834 and about 1848 remain unclear. Records stating that Ritchie was a potter are scarce, but in 1860 the census clearly records that sixty-one-year-old Moses Ritchie was a Catawba County, North Carolina, potter.[213] In 1850, Moses’ son Thomas was a Lincoln County potter, while in neighboring Catawba County, his son Henry made pottery, and his son Joseph worked as a brick mason. Thomas Ritchie, whose shop seems to have included potters from the Catawba Valley’s Johnson and Carpenter families, continued his father’s trade.[214] His shop’s wares (Figure 35) are among the finest made by North Carolina’s alkaline-glazed stoneware makers. In Catawba County, pottery was also being made by their relative, Paul Ritchie.[215] Ritchie potters intermarried with and worked alongside Johnson and Carpenter potters in Lincoln and Catawba counties.

The Pottery

Apart from examples of earthenware signed by William F. James and some items long associated with early Yadkin Valley area families, little is known about the objects produced by individual Yadkin Valley potters, whose work over many years undoubtedly resulted in a variety of wares. However, two pottery production sites have been identified, and surface-collected artifacts from these sites offer clues as to what the area’s potters produced. One site is in Huntsville, Yadkin County, and the other is in Davie County, a few miles away.[216]

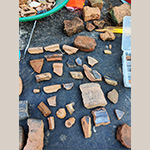

Sherds (Figure 36) from the Huntsville site have been collected over many years by a lifelong Huntsville resident and her mother from a low-lying area near a spring and a small stream within the borders of old Huntsville.[217] A rock wall constructed nearby from collected stones may have been made using the demolished kiln’s remains. It is possible that this site was occupied by Vestal family potters from the early 1800s, and afterward by journeymen and potters who may have been trained in the trade by the Vestals or someone who followed them.[218] If this is the case, the location supported pottery production for approximately a half-century.

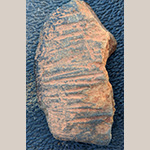

Sherds from the Huntsville site indicate that storage jars with everted rims (Figure 37), dishes with well-defined marlys (Figure 38), and press-molded pipeheads were manufactured on the site. Glaze colors range from dark brown to medium orange, with some exhibiting a mottled, greenish-gray appearance (Figure 39). Decorative slip trailing (Figure 40) was added to some wares, creating linear banding and also incised zigzag lines bounded by two parallel lines along the shoulder of the pots. This incised zigzag line around the circumference of the pot is commonly found on Guilford and Randolph County Quaker-made wares (Figure 41). Salt-glazed stoneware sherds (Figure 42) are present in the collection, raising questions as to whether both stoneware and earthenware were produced at the site, or whether they represent common household debris mixed into a waster pile, which was not uncommon at production sites.

Examples of kiln furniture from the Huntsville site (Figure 43) include rectangular tiles made of clay with one face bearing a series of scratched or combed parallel lines. The grooved surface helped prevent glazed wares from sticking to the tiles during firing. Similar kiln furniture has been found at the Davie County site (Figure 44) and at an unexcavated pottery site in Jamestown, Guilford County, North Carolina (Figure 45), where Vestal potters were present. Archaeologists Samuel D. Smith and Stephen T. Rogers have found similar kiln tiles (Figure 46) at a site associated with Silas Vestal in Greene County, Tennessee. Describing them as “pieces of thick, rectangular shaped tiles,” Smith and Rogers note that the tiles “have flat bottom surfaces and upper surfaces with parallel ridges and grooves or basket weave-like impressions.”[219] The use of such tiles suggests that the kilns on these sites were tall, unlike groundhog kilns, allowing wares to be stacked.[220]

Surface-collected sherds (Figures 47-49) from the Davie County location are similar to those found in Huntsville and likely represent a James pottery site. When interviewed, nearby residents said William F. “Potter Bill” James’ kiln was not far from this location in Jamestown.[221] Multiple generations of James potters may have worked at the site, including Potter Bill’s father, William Alexander James, and perhaps his grandfather, Cornell James. The current collection lacks examples of Potter Bill’s characteristic rings and the bold, rim-attached handles from which they were hung, suggesting that it may not be the only James pottery site in the area.

Many of the sherds from the Davie County site bear a dark brown glaze over a light-to-medium red-colored paste. Most glazed examples lack the smooth, glossy surface frequently seen on well-made lead-glazed earthenware. The effect may be due to underfiring or the use of an insufficient glaze mixture. Some finished wares (Figure 50) found by collectors not far from Davie County are similarly glazed. They may have been made at this site or nearby, but further research is needed to be able to definitively locate their place of manufacture.

The tall storage jar in Figure 51 came from an estate sale in Forbush, Yadkin County. Forbush, a community situated a short distance from Huntsville and the shallow ford of the Yadkin River, was home to numerous early settlers in Surry (later Yadkin) County, including the Williams family, from whose estate this jar was acquired. Its glaze, coating only its interior, handles, and shoulder in a crisscross fashion, resembles the glazing found on sherds from the Huntsville and Davie County sites. Two jars in Figure 52 have similar crisscross glaze and may be associated with the Williams family storage jar. Another large jar (Figure 53) resembles the one in Figure 51 and was probably made by the same potter. The similarity in form and handle placement of these two large jars and those made by Tennessee potters C. A. Haun and J. A. Lowe (Figures 54-55), as well as their shared features with wares produced by Henry Watkins and other Quaker potters in Guilford and Randolph counties, is striking. Could the form have been introduced by Huntsville potter Simon Bohannon, who was associated with Haun after leaving North Carolina, or perhaps by a Vestal, a Bohannon, or another Yadkin Valley potter who migrated to Greene County? While the current material evidence is intriguing, a definitive answer awaits further research and new discoveries.

The jar described above (Figure 51), the slip-trailed child’s plate (Figure 56), the jar (Figure 57), and the bowl (Figure 58) were acquired from Williams family estate sales in Yadkin County’s Forbush community. Members of the Williams family were involved in the slave trade and the production of distilled spirits and were among the area’s earliest and most prominent residents. Given the number of earthenware pottery makers nearby and the absence of negating evidence, the assumption that Yadkin Valley potters produced these items seems reasonable.

John Bivins Jr. described chambersticks like the ones in Figure 59 as unglazed, late-period Moravian, possibly from Bethania.[222] An example similar to the painted one is owned by a James family member who claims it was made by William Franklin “Potter Bill” James.[223] Since no evidence is presently known connecting this form to North Carolina’s Moravian potters, their manufacture by one or more Yadkin County or Davie County potters seems likely.[224]

The footed pitcher in Figure 60 came from a home near Pinnacle in Stokes County, a site about twenty-five miles northeast of Huntsville. Poor lead glaze adhesion created an interesting, but unusual surface. An antiques dealer observed jugs exhibiting similar glaze failure in a Yadkin County shed near East Bend and the Yadkin River near Huntsville, further corroborating the possibility that it was produced locally.[225]

With the benefit of future research, it is likely that the Yadkin Valley origin of many more unattributed earthenware pottery examples found in private and museum collections will be proven. However, as this article has demonstrated, we currently know more about the potters than their wares.

Conclusion

Yadkin Valley potters sustained an earthenware tradition for more than a century, long after others turned to manufacturing more durable stoneware pottery. Their impact on pottery production extended well beyond the Yadkin Valley – the potters who worked and were trained here carried their craft into southwestern Virginia, northeastern Tennessee, further south, and even into the Midwest. While collectors often point to Moravian influence on pottery made along the Great Wagon Road, the style may owe just as much to artisans from the Yadkin Valley, many of whom were trained by the state’s Quaker potters including the Vestals and their successors. This tight network of Yadkin Valley potters, from Peter Myers in the late eighteenth century to Bill James in the early twentieth century, kept earthenware production alive in the region and left a lasting imprint on Southern pottery traditions.

Stephen C. Compton is an independent scholar and author specializing in North Carolina pottery. He can be reached at [email protected].

[1] For studies focusing on the reassessment of North Carolina slip-decorated earthenware once attributed to the Moravian potters in Wachovia, see the 2009 and 2010 volumes of Ceramics in America, specifically Luke Beckerdite, Johanna Brown, and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton, “Slipware from the St. Asaph’s Tradition,” Hal E. Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh, “The Quaker Ceramic Tradition in Piedmont North Carolina,” and Linda Carnes-McNaughton, “Solomon Loy: Master Potter of the Carolina Piedmont,” in Ceramics in America edited by Robert Hunter and Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2010); Stephen C. Compton, “Research Note: The Eighteenth-Century Potters of Salisbury and Rowan County, North Carolina,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 39 (2018): 143-156; Scott W. Smith, “Documenting Early Catawba Valley ‘Potters’” Traditions in Clay 13 (Raleigh, NC: The North Carolina Pottery Collectors’ Guild, Fall 2006): 2-7.

[2] The shallow, rocky upstream waters of the Cape Fear River’s tributaries likewise hindered significant riverine trade with interior Piedmont region settlements like those established near the Great Wagon Road’s crossing of the Yadkin River.

[3] This region was some distance from relatively cultured settlements like Hillsborough and Cross Creek and Fayetteville.

[4] For information about the state’s Moravian potters, see Hunter and Beckerdite, eds., Ceramics in America 2009; Stephen C. Compton, North Carolina’s Moravian Potters: The Art and Mystery of Pottery-Making in Wachovia (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing by arrangement with Fonthill Media LLC, 2019). For information about Rowan County potters see Compton, “Research Note.”

[5] Harden Taliaferro, Fisher’s River (North Carolina) Scenes and Characters (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1859), 18-19.

[6] Taliaferro, Fisher’s River (North Carolina), 220-221.

[7] For information on pottery along the Great Wagon Road, see Betsy K. White, Great Road Style: The Decorative Arts Legacy of Southwest Virginia and Northeast Tennessee (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006); Roderick J. Moore “Earthenware Potters Along the Great Road in Virginia and Tennessee,” The Magazine Antiques, September 1983, 528-537; Johanna Miller Lewis, Artisans in the North Carolina Backcountry (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1995).

[8] William E. Rutledge Jr. and Max O. Welborn, “Huntsville,” in An Illustrated History of Yadkin County: 1850-1965 (Yadkinville, NC: William E. Rutledge, Jr. and Max O. Welborn, 1965), 25.

[9] William S. Powell, The North Carolina Gazetteer: A Dictionary of Tar Heel Places (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1968), 241.

[10] “The Great Wagon Road,” in The Way We Lived in North Carolina, ed. Joe A. Mobley (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 81.

[11] “Tyre Glenn,” 1860 U S Federal Census Slave Schedules, Yadkin County, NC.