In 2001 Burritt on the Mountain, a historic house and park in Huntsville, Alabama, acquired a handsome corner cupboard (Figure 1) that is signed and dated “Thomas S. Doron Montgomery Ala July 1852” on the bottom of a hidden drawer fitted into the lower rail (Figure 2).[1] Nearly twenty-five years later, little remains known about the corner cupboard’s maker, Thomas S. Doron. Because of the scant knowledge about Doron and his work, the discovery of his signature raised several questions. Seemingly the most basic, but also the most foundational, who was he? Where was Doron from, how did he come to be working in Montgomery, and where in the city did he conduct business? Did Doron set up his own shop or work with more established craftsmen in the city? Were familial connections important to his business and life in Montgomery? Now that a signed piece has been identified, might this cupboard serve as a starting point for linking other surviving pieces to Doron?

As the date on the cupboard indicates, Doron was living and working in Montgomery when the city took center stage not only in the region but across the nation in the years leading up to the Civil War. How did Doron’s life and work fit into the history of the new Alabama state capital? And how did Doron compete with other local Alabama cabinetmakers as well as far-flung makers whose imported furniture found a ready market in Montgomery? Finally, how did the Civil War shape Doron’s work and the furniture trade more broadly in Alabama?

This article seeks to address these questions, offering the first detailed discussion of Thomas Doron and his work. It introduces readers to a previously unknown cabinetmaker and provides foundational research on Doron’s life and the only signed piece of furniture currently linked to him. This signed corner cupboard demonstrates his skill as a cabinetmaker, and stylistic analysis suggests that other surviving pieces may also be his work. This article aims both to provide scholars with the foundation for future research on Doron and to provoke new questions to be asked of known pieces of unsigned Alabama furniture that may have a connection to Doron. While it answers a number of questions, the research for this article also invites a number of questions that are beyond the scope of this study. Because little is still known about Doron, this article is first in what is hoped to be many studies that examine Doron himself, the furniture he produced in Montgomery, and his place within local, regional, American, and perhaps even Caribbean woodworking trends.

Thomas S. Doron

Named for both his grandfather and his uncle, Thomas Stacy Doron (ca. 1820-1886) was born around 1820 in New Jersey.[2] Thomas was from a large, close-knit, middle- or working-class family from Mount Holly and nearby Buddtown. His parents, Joseph Doron (1785-1857) and Mary Johnston Doron (d. 1858), married in 1805 and had seven children.[3] Of all the Doron siblings only one, Charles S. Doron (1823-1896), remained in New Jersey, settling in Burlington County.[4] Census and family records indicate that the other six Doron children headed either south or west in search of new opportunities.[5]

Thomas’ uncle, Stacy Doron, was a wood merchant who lived next door to the family in Burlington County, so Thomas may have learned his trade close to home, but like his siblings, he had a sense of adventure and a desire for opportunity that took him away from New Jersey.[6] Before permanently moving south, Thomas’ desire for work and opportunity took him to the Caribbean. In a manifest of passengers (Figure 3) taken on 7 June 1848, “Thomas S. Doran. . .Cabinet Maker” appears arriving at the port of Philadelphia from Trinidad de Cuba as a passenger aboard the brig Importer, a mercantile ship that carried bulk cargo including timber.[7] By the mid-nineteenth century the market for Cuban mahogany had increased due to the deforestation of the species in other tropical locales, so it is possible that Thomas was working in Cuba as an agent for his uncle to procure the valuable lumber to be shipped to the United States.[8]

While it is not yet known how long Thomas spent in Cuba or whether he worked solely for his uncle or, as the manifest suggests, as a cabinetmaker on the island, Thomas next appears in the records in Montgomery, Alabama, two years later in 1850. It is likely that once he was situated in the growing city, he persuaded his younger brothers to migrate to the region, as records indicate that it was not long after 1850 that his siblings joined him in the city. According to mid-nineteenth-century federal and Alabama census records, William S. Doron (c. 1825-1899), a shoemaker; Budd W. Doron (c. 1828-1872), a wheelwright and coach maker; and George R. Doron (1831-1880), a tailor, all followed Thomas south, settling and setting up shop in Montgomery in the 1850s and 1860s.[9] The siblings’ choice to move not only out of New Jersey but to settle in Alabama suggests that something drew them to this region in particular. What were the circumstances in Montgomery in the middle of the nineteenth century that attracted the journeyman cabinetmaker Thomas Doron and his brothers to the city?

Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery was established in 1819 – the same year Alabama gained statehood – through the merger of the towns of East Alabama and New Philadelphia. It was strategically situated along the banks of the Alabama River and the Federal Road, making travel and commerce from the Gulf Coast through Georgia more accessible (Figure 4). In 1820, the new town had just over four hundred inhabitants. While early settlers to the region had to contend with underdeveloped roads, during the 1820s transportation methods in Alabama rapidly improved from early log or plank-paved roads to railroads.[10] On the rivers, slow keelboats and barges were replaced by efficient paddlewheel steamboats that traveled up and down the rivers night and day. While the industrialization of the region created new opportunities for migrants such as the Doron brothers, the influx of settlers seeking agricultural and commercial prospects came at the expense of Indigenous people, who were steadily displaced. By 1838 the Muscogee, the last of the Indian Nations in the region, were forcibly removed along the Trail of Tears.[11] A different form of oppression soon defined Montgomery. By the 1840s, the city, located in the heart of the Alabama Black Belt and fueled by enslaved labor and king cotton, was thriving. It became the state capital in 1846 (Figure 5).[12] By this time, Montgomery had nearly five thousand residents, almost half of whom were in bondage and whose unfree labor powered the city’s growth.[13]

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the combined forces of the developing Industrial Revolution and a rapidly growing population in the North forced many young, skilled craftsmen to seek employment in the country’s new western territories, including Alabama.[14] While the region’s burgeoning growth drew migrants from both neighboring states and from the Northeast, there is a distinct pattern for where these two groups of migrants settled and the forms of employment they sought in the region. Understanding these patterns helps explain the Doron family’s choice to settle within the city itself. An examination of the 1850 and 1860 census records for Montgomery County reveals that settlers in Montgomery County who moved from neighboring southern states were much more likely to live outside the city, pursuing agricultural livelihoods as farmers and planters. By contrast, a far higher proportion of migrants from mid-Atlantic and northern states such as New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, and Connecticut settled within the city of Montgomery, where they engaged in skilled trades, opened businesses, and practiced professional occupations.[15] That Thomas Doron was a cabinetmaker, William was a shoemaker, Budd was a wheelwright and coachmaker, and George was a tailor fits squarely within this larger urban migration trend within the city. Viewed within the larger picture of migration patterns, their choice of Montgomery reflected not only personal opportunity but also the growing city’s ability to attract artisans and entrepreneurs seeking to profit from its expanding economy. With this as the backdrop in the city, what was the furniture-making trade like in Montgomery when Thomas Doron moved to the city?

Early Furniture-Making in Montgomery

Alongside the flow of people moving into the new state, goods were also moving south. Northern manufacturing centers, including New Jersey, developed a reputation as a “southern workshop” because many of their manufactured goods, including furniture, leather products, and clothing, were shipped to the South.[16] This flow of goods and people likely benefited craftsmen like the Doron brothers and drew them to Montgomery as the trades they practiced were in high demand in the burgeoning city. It also likely helped craftsmen who were already established in the region, like John Powell Jr., for whom Thomas Doron initially worked in the city.

John Powell Jr. (Figure 6) was one of the early inhabitants of Montgomery. Powell was born 8 February 1796 in Warren County, North Carolina.[17] He left North Carolina in 1818 and ventured out to Fort Claiborne in the new territory of Alabama where he married Matilda Morgan in 1824. Shortly afterwards they settled in Montgomery where he initially established a stagecoach and buggy business and then opened a large furniture shop that produced goods for several decades.[18] In 1841 Powell formed a brief partnership with L. H. Dickerson (b. 1820), a cabinetmaker and undertaker from New Jersey, who had moved to Montgomery by 1840.[19] After a year in business, Powell and Dickerson dissolved their partnership, with both men opening rival furniture businesses in the city.[20] Powell continued to place advertisements (Figure 7) in the local papers until the dawn of the Civil War, telling potential customers that he stocked furniture imported from Mobile and received supplies on a daily basis. Powell seems to have struck a careful balance to remain in business by skillfully navigating the combined forces of local competition and the flood of imported furniture that came into the city from ports along the East Coast, the Gulf, and Europe.[21] Operating a large furniture shop or warehouse that employed several craftsmen and offered a variety of services, Powell was constantly recruiting young talent like Thomas Doron to expand his business and ensure his financial success and longevity in the city. He also offered a range of custom work that gave his business a substantial advantage over other cabinet shops, a fact which may have enticed Doron to work for Powell.[22]

In the 1850 Alabama census, “David Deren” is listed as a thirty-year-old cabinetmaker from New Jersey who was living in the household of John Powell.[23] Despite the fact that both the first and last names differ from those on the bottom of the drawer, it is possible that this is a reference to Thomas Doron, since, as of yet, a Thomas Doron matching the cabinetmaker’s description has not been identified in an 1850 census list.[24] The same census lists Samuel Walker, a young cabinetmaker from Alabama also living in Powell’s household. It is likely that both men worked for Powell and that, at twenty-one years old, Walker was a newly hired journeyman, while Doron, at thirty, was perhaps the foreman. Several of Powell’s sons were also employed in his business as apprentice cabinetmakers. According to Glen Beckwith, John Powell’s great-great-grandson, skilled enslaved craftsmen worked in Powell’s shop producing furniture alongside white tradesmen. In 2014 Beckwith wrote that, “John Powell had black slaves … who prided themselves better craftsmen than the freemen …. These black slaves had their own quarters in town from which they commuted back and forth unsupervised.”[25] The 1850 and 1860 slave schedules support Beckwith’s claim. In 1850 John Powell is listed as enslaving eleven people, and by 1860 the number of individuals had grown to seventeen, housed in six dwellings.[26] Powell’s reliance on enslaved labor at the moment northern artisans like Doron entered his shop highlights how white cabinetmakers expanded profits not only through the use of journeymen and apprentices but also through the exploitation of skilled enslaved craftsmen. The social, economic, and racial dynamics of Powell’s shop in which newly arrived craftsmen from the North worked alongside enslaved craftsmen provide insight into the complex social and labor structures that shaped Doron’s early years in Montgomery. Thus, Doron’s life and craft were entangled not only with his own skill but with the skill of those in bondage with whom he worked.

Thomas Doron’s Signed Corner Cupboard and Attributed Furniture

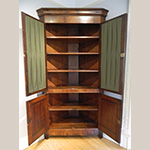

Thomas Doron’s fashionable corner cupboard (Figure 1) speaks to his skill in both the design and manufacture of functional and aesthetically plain furniture. Standing over 8 feet tall, the corner cupboard has an understated elegance and visually pleasing proportions. Close examination of the piece makes it clear that Doron carefully calculated the dimensions of various components as he planned its appearance. His overall design and ratios are most evident when the doors are opened (Figure 8). The overall width-to-height ratio for the piece is 1:2, and there is a 2:3 ratio between the height of the lower paneled doors and the glass section above. A quarter-inch half-round molding marks the top of the lower section. The upper glazed doors are 4 feet tall and are marked at the top by another quarter-inch half-round. The side stiles that run all the way up the piece to the cornice are 8 feet tall by 5 inches wide. Both the lower skirt and upper frieze are 5 inches high. Instead of knobs or pulls, Doron used locks and keys on the doors and drawer to create a clean, uninterrupted surface. In placing so much emphasis on these exacting sizes and geometric patterns, Doron ensured that the corner cupboard’s design conveyed a sense of balance and harmony.

Further elevating the cupboard, the primary wood is mahogany, with crotch mahogany veneers on the two lower paneled doors and case piece. By the mid-nineteenth century, veneers were cut with a circular saw instead of the manual veneer web saw of earlier periods. The process of decorating with veneers, however, remained time-consuming and costly.[27] Doron would have needed specialized knowledge to use the hand tools and materials required for applying veneers, including hot animal hide glue, veneer hammers, and custom-made cauls that fit over moldings and other irregular contours. He would also have needed the ability to work with the French polish that was applied on the surfaces to make the mahogany glow.

Beyond technique, Doron clearly had an eye for design as the crotch-pattern veneers on the panels are carried up through the case piece, producing a harmonious flow and unified pattern of the fancy grain. The significance of the contemporary appreciation for this technique can be seen in Blackie and Son’s The Cabinet-Maker’s Assistant (1853) which states that when “moldings are cross veneered with rich wood, of small and diversified figure, their appearance is much improved, and the general beauty of an article of furniture is thereby greatly enhanced. For this purpose, mahogany curl veneers are often used, with the best effect.”[28]

The secondary woods used in the corner cupboard consist of native cypress that Doron used for the tongue-and-groove backboards, which are half an inch thick and over 18 inches wide, and poplar and yellow pine, which he used for the dovetail drawer and guide system. The dovetails (Figure 9) of the secret drawer are finely executed. The interior has a dark stain that was probably added in 1935 when the piece was repaired.[29] In its current state, the pair of glazed doors, each with two large panes of glass, carry new green silk curtains. While the curtains are not original, nail holes on the inside of the glazed doors suggest that they originally had curtains. Atop the doors, large ogee Gothic arches draw the viewers’ attention to the ribbon or Dutch ripple molding (Figure 10) that runs below the cornice. This type of wavy molding, like the fancy mahogany veneers, was mechanically manufactured and available in the United States from the 1840s but required both skill and a good eye for design to apply.[30] Doron used pointed-arched doors and book-matched, vertically oriented mahogany grain veneers to generate subtle upward movement on the cupboard’s façade. Finally, the harmonious balance of the cupboard is crowned by the cornice molding, the profile of which echoes the S-shaped ogee of the pointed-arched doors.

As journeymen were often paid by the piece, his signature (Figure 2) on the bottom of the drawer assured that he would receive both credit and payment for his work. However, the skill and precision with which he constructed this piece, and the fact that he had only recently arrived in the city when he made the cupboard, suggest that inscribing his name on the drawer was also a way for Doron to ensure his status with his employer, claim his position within the hierarchy of the workshop, and establish his reputation in the community as a fine craftsman.

Doron’s corner cupboard provides the first insights into the work he produced during his time in Montgomery. From the detailed analysis of the piece, it is clear that he was working within established design principles of the neat and plain style common in the South. However, with its clear attribution, this signed piece also serves as a touchstone for identifying other work that may have been made by Doron. Using the signed cupboard as a point of reference, a similar corner cupboard (Figure 11), transferred from the Friends of the Alabama Governor’s Mansion to the collection of Old Alabama Town in 2003, is attributed to Doron.[31] This cupboard is slightly smaller than the signed piece; however, the width to height ratio is the same (1:2). The glazed doors, like those on the signed piece, are made of solid mahogany and decorative veneers are used on other surfaces. There is a slight variation in the secondary wood, which is exclusively yellow pine in this piece. The 45-degree bevel on the inside stiles of the doors is treated in the same manner as on the signed example, as is the dovetail joinery of the drawer.[32] The Gothic pointed arches (Figure 12) over the doors have the same rounded edge and ogee pattern but begin with a curved S-lobe.

The primary differences between the two pieces are found in the top and bottom of the cupboards. Whereas the signed piece has a straight skirt, the smaller cupboard has a shaped skirt that forms the bottom of the drawer front (Figure 13). In the unsigned piece, ripple moldings frame the panel of the lower doors, and the cornice has a cove instead of crown shape. However, even with these minor decorative changes, the overall appearance and specific design and construction techniques closely resemble those of the signed cupboard. With such striking similarities between these two corner cupboards, it is probable that the smaller version can be attributed to Thomas Doron, or to Doron and other members of the Powell workshop.

This attribution is further supported by the accession records held by Old Alabama Town. Since its arrival in the collection this unsigned corner cupboard has been attributed to Thomas Doron. In 2001, furniture scholar and dealer Edward Patillo examined the signed cupboard, this smaller example, and other related pieces.[33] In his appraisal, Patillo first made the connection and attribution to Doron. While further research may refine our understanding, the combination of the scholarly appraisal and compelling physical evidence suggests that Doron likely had a hand in producing the unsigned corner cupboard.

A set of unusual enclosed-front mahogany bookcases (Figure 14) now at the First White House of the Confederacy may also have been made by Doron during his time working in Powell’s workshop.

The First White House of the Confederacy served as the home of Jefferson Davis and his family during their brief stay in Montgomery in the spring of 1861 before they moved to Richmond, Virginia.[34] The bookcases are extremely tall and narrow with a 1:3 width to height ratio, which creates an elongated appearance. The opposing side of each case is undecorated, indicating that they were likely custom-made mirror images of one another ordered to fit corner walls; it is likely they were designed to fit on either side of a doorway, passage, or fireplace. The sides that would have been visible have a round edge with curved moldings. A brass plaque that was added more recently on the visible side of each bookcase reads:

THIS CABINET WAS THE PROPERTY OF

THOMAS WATTS

AND WAS USED BY HIM WHILE

WAR GOVERNOR OF ALABAMA

AND MEMBER OF

PRESIDENT DAVIS CABINET

PRESENTED TO THE

CRADLE OF THE CONFEDERACY CHAPTER

BY HIS FAMILY

This inscription suggests that the bookcases were designed and constructed as built-ins for the Watts Mansion on Adams Street in Montgomery.[35]

Each bookcase is constructed of three sections that are secured together with iron bolts (Figure 15) through the middle along each side. The bottom has a deep drawer with a pair of turned knobs. Bracket feet (Figure 16) with fancy swirl patterns cut out in the pillar and scroll style support the case, their delicacy defying the weight of the piece. Each bookcase contains five adjustable shelves, each with a double-beaded front. The back consists of tongue-and-groove board panels. The front is enclosed by a pair of glazed doors holding four vertical panes, each measuring 21 inches high by 12 inches wide. An astragal molding with a ripple design is attached to the right-side door to cover the gap between the doors when they are closed. At the top of each door is a Gothic arch (Figure 17) with a beveled edge and the same ogee pattern and curved S-lobe as the smaller corner cupboard. The top section is a bonnet cornice. The simple square cap is not the original molding, and there are a variety of other small replacements and missing parts.

While stylistic features provide one point of connection between the pieces, similarities in construction techniques offer additional supporting evidence. A comparison of the bookcases with the corner cupboards shows a number of similarities with regard to joinery. All the drawer fronts are constructed with half-blind dovetails with mahogany veneered faces. The drawer bottoms consist of a single board with the grain running parallel to the front. The sides of the drawer bottoms are beveled to fit into a side dado, with the bottom edge of the drawer serving as the runner. The fine pins between the dovetails are the same size and shape and appear to be similarly spaced. Rubbings of the dovetail joints taken from the two cupboards and the bookcases confirm this similarity (Figure 18). All of the furniture features tongue-and-groove vertical back panels, reinforcing these construction parallels. This consistency in construction details between the signed cupboard, the smaller cupboard, and the bookcases lends further evidence to support their attribution to Thomas Doron.

Edward Patillo, who appraised both cupboards, also examined the bookcases for the First White House and reached the same conclusion. He attributed them to Thomas Doron, thereby reinforcing a consistent attribution across the group.[36] While there are some obvious differences, such as the treatment of fancy scroll feet, the deviations in design and construction may reflect the collaborative nature of Powell’s large shop, in which Doron worked alongside Powell’s sons, Samuel Walker, and several enslaved craftsmen. However, overall, there seems to be sufficient affinity with the work of Thomas Doron to argue that the bookcases can be attributed to him and John Powell’s shop.

Competition

Just as the steamboat had increased trade and commerce decades earlier, by the mid-nineteenth century the rail system profoundly shaped the way people in Montgomery lived and conducted business. With the expansion of the railroads, goods, including furniture, were more readily distributed to the region’s growing population and could move more easily within the city itself and to elite homes in the surrounding areas.[37] As the ease with which both people and goods could move increased, Montgomery cabinetmakers faced competition from both importers and craftsmen working in other states. For example, by the mid-nineteenth century Cincinnati had become a leading manufacturing and exporting center of furniture in the United States heartland.[38] In addition to large urban centers like Cincinnati, craftsmen were also springing up in smaller communities where they tried to find their niche. For example, William John Howard, a wealthy plantation owner in Macon County who turned to woodworking as a hobby, became a source of formidable competition when he opened his factory at Cross Keys on the road from Montgomery to Tuskegee, near Shorter’s Depot and the West Point Railroad in 1851.[39] In a bid to compete with Montgomery cabinetmakers, Howard advertised (Figure 19) that he was willing to deliver merchandise to the railroad without extra charge.[40] Although he advertised his business in local papers as the Alabama Chair Factory, he offered a full range of household furniture including bureaus, pier tables, and secretaries, and was thus a constant source of competition for Doron and other cabinetmakers working in Montgomery.

An example of William John Howard’s furniture – a handsome two door, two drawer wardrobe (Figure 20) with his stencil mark “WJH Man” on the inside – is currently on display at Old Alabama Town. A very large piece of furniture, the wardrobe is constructed in several sections that are held together with locking wedges (Figure 21), which make for easier transportation because the piece could be taken apart and reassembled. Howard’s choice of wooden wedges provided an inexpensive alternative to the costly metal bolts Doron used in his bookcases and highlights his preference for economical solutions.[41] The same cost-conscious approach extended to his materials. Howard was known to have used wood from trees on his plantation and advertised that he used southern magnolia.[42] Upon examination of the wardrobe in 1995, some doubts arose as to the wood used, so several samples were sent for analysis. The samples were identified as Liriodendron tulipifera, commonly known as American tulipwood or American whitewood, tulip poplar or yellow poplar.[43] Therefore, the primary wood of the wardrobe is poplar which has developed a wonderful golden-brown patina, and the secondary wood is yellow pine; none of the samples suggest that magnolia was used in the piece. In the nineteenth century, passing poplar off as the less abundant magnolia was a shrewd sales tactic, especially when poplar was typically used as a secondary wood. By using local woods, Howard kept production costs down, and by staining it dark he avoided being branded provincial.

By contrast, Doron’s choice of mahogany as the primary wood for his pieces signaled a different approach. Where Howard economized with the use of native grown and less desirable poplar, Doron relied on costly imported mahogany and decorative veneers to elevate his pieces and project a sense of refinement. Doron’s work demonstrates an alignment with urban cabinetmaking traditions that emphasized fashionable materials and finish, and it may also suggest a continued relationship with his uncle and his time spent importing mahogany. The contrast between Howard’s pragmatic use of local poplar and Doron’s investment in imported mahogany underscores not only differences in aesthetic sensibility but also their distinct strategies for competing in Montgomery’s furniture market.

If Howard and Doron diverged in their material and stylistic choices, they were both nevertheless enmeshed in the labor systems that underpinned furniture production in the South. In 1979 Milo Barrett Howard Jr., then Director of the State of Alabama Department of Archives and History and the great-grandson of William J. Howard, recounted a family tradition regarding his ancestor’s furniture business. He wrote:

… Mrs. Howard (Ann Flewellen Billingslea) resented the chair factory as a hobby which diverted great-grandfather’s attention from what she thought was the more important business, the plantation. It consisted of about 1800 acres and in 1850 worked 56 slaves. Frances Barnes (a first cousin) said that Ann had the slaves, or some slaves set the factory on fire. I hasten to say that I am not descended from Ann but from Major Howard’s second wife.[44]

If family history is correct, it seems possible that, despite the fire, a driving factor in the success of Howard’s Chair Factory was the exploitation of an enslaved workforce. Thomas Doron, likewise, participated in and benefited from the exploitation of enslaved labor. On 1 December 1856, he purchased an enslaved boy for $200.[45] At fifteen, the young man may have already received some training in cabinetmaking and was still young enough to be trained by Doron; alternatively, the youth may have been employed as a personal servant. Whatever his role, the transaction demonstrates that Doron, like Howard and John Powell, participated in the broader system of enslaved labor that sustained Montgomery’s furniture industry and the city and surrounding areas more broadly.

Real Estate Investments

As the 1850s drew to a close, Doron began investing in Montgomery’s built environment. According to the Montgomery city directory, by 1859 Thomas was staying at the Madison Hotel, a boarding house at the corner of Market and Perry streets, but he was beginning to buy real estate.[46] Perhaps because of Howard’s and Powell’s fates – Powell’s workshop, too, had caught fire and burned to the ground in 1855 – Doron acquired fire insurance for all of his properties, and the surviving documents (Figure 22) provide a way of tracking his real estate investments.[47] On 15 February 1859, Doron bought Lots 37 and 38 on Jefferson Street and Lot 1 on the west side of Bainbridge Street in the part of town known as New Philadelphia. Lots 37 and 38, which correspond to 516 and 522 Jefferson Street, were well-situated properties. For example, the State Capitol, which was built on “Goat Hill” in 1850-51, fronted Bainbridge Street just a couple of blocks away from Doron’s property.

At the end of the 1850s, the four Doron brothers who had relocated to Montgomery – Thomas, George, Budd, and William – pooled their resources and formed a real estate company called George R. Doron and Company.[48] Investing at an opportune time, they purchased Lots 6, 7, 8, and 10 on Adams and Perry streets. On 29 February 1860, Budd and Thomas borrowed money from Montgomery coachmaker and businessman A. B. Pierson, who was also a New Jersey native, to build on some of their vacant lots.[49] At 522 Jefferson, on the corner of Jefferson and Bainbridge streets, they built a large, two-story, wood-frame dwelling with a shingle roof, front porch, and a one-story rear addition.[50] George Doron and his family lived here along with his brother William, a widower. For collateral, the Dorons used Lot 6 on the south side of Adams, Lots 7 and 8 on the west side of Adams, and Lot 10 on the west side of Perry Street. Both Adams and Perry streets are significant for Doron’s trade. The previously discussed bookcases were built-ins for the Watts Mansion, which was located at 834 Adams Ave, and John Powell’s furniture warehouse and cabinet-repair shop were located at 8 and 10 Perry Street, respectively.[51]

In the 1860 census, Thomas, a bachelor, lived in Montgomery’s 1st District.[52] Thomas’ real estate was valued at $7,500, and Budd’s real estate holdings were worth $11,000.[53] John Powell lived just four buildings down the block from Thomas Doron. Between them was an upholsterer, John Shaw from Ireland, and two cabinetmakers, John Muller from Germany and Samuel Prickett, a distant cousin of the Dorons from Mount Holly.[54] All these men may have known and worked with Doron or Powell. Doron’s cousin Prickett eventually became a partner in Powell’s furniture business. Finally, the Montgomery County Courthouse and several churches – Methodist, Presbyterian, and Catholic – were all located within a few blocks. As these examples suggest, the area was prime real estate in the mid-nineteenth century, with Perry Street dubbed the “Fifth Avenue of Montgomery.”[55]

The Confederacy Established

As the city was booming and the Dorons were ensuring their place within the landscape of Montgomery, the country was thrown into the upheaval of the Civil War, and the Dorons were at the heart of the conflict.[56] Two weeks after the Confederate States of America were declared in the Alabama State Capitol on 4 February 1861, Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as president on the front steps of the Capitol, surrounded by a crowd gathered on “Goat Hill.” The Confederate government was offered the Montgomery Insurance Building as a location for the seat of government. The building was a large, functional structure located on the northwest corner of Bibb and Commerce streets, just blocks from the Alabama River and the railroad lines. Some of the furnishings for the renamed Government Building came from Powell’s store, including a desk, table, and chairs that were used by Henry Capers, a clerk for the Treasury Department.[57] While it is not yet known if Doron made or contributed to any of this furniture, it is possible that he was still working for Powell at this time and, if so, it is likely that he would have been a part of their construction. Budd Doron, a coach maker, appears in the Confederate Citizens File in 1862 when he sold the Confederate States material, including a coupling and a tongue to a caisson, each worth $5, and a tongue for a gun carriage worth $10.[58]

While Budd was able to sell his wares to the newly formed government, the furniture business, as with trade in other luxury goods, experienced a steady decline as the war dragged on.[59] An eyewitness account of how the war years impacted the furniture business in the city and the surrounding areas appeared in the Montgomery Journal in 1916 in a column entitled “The Lady of the Old Armchair.” It stated that Mr. Powell’s “furniture establishment and his warehouse was groaning with its immense stock of goods when the war closed. He carried the most beautiful mahogany and rosewood and walnut. I know of one wardrobe that he sold after the war for five hundred dollars ….”[60] The extravagant cost of this piece of furniture is an excellent example of the inflation that plagued the war-torn southern economy.[61] With the collapse of the economy, the price of most goods soared. Not only was the Confederate currency worthless, but the overprinting of greenbacks to fund the war directly contributed to the high inflation.

No doubt Doron also felt the impact of this uncertain economy. Expensive mahogany furniture, such as the cupboards Doron produced, would have been increasingly difficult to sell in these conditions. As households prioritized survival and basic necessities over fashionable goods, the market for refined urban cabinetmaking in Montgomery dwindled. Doron’s reliance on costly imported materials would certainly have limited his opportunities in a city where even Powell’s large warehouse struggled to move stock.

Reconstruction

Following the Civil War, financial hardship in the Black Belt region, especially around Montgomery, was compounded by both the Depression of 1873 and the steady decline in the value of cotton, which fell nearly 50 percent from pre-war levels, thereby decreasing the major source of credit in the region.[62] Despite these challenges, Doron and his brothers had accumulated assets that they could fall back on, such as rental property. Business was slow during the Reconstruction period, and real estate in Montgomery was scarce and expensive. As an illustration of this, in the 1870 Federal Census, John Powell had eighteen people recorded as part of his crammed household, including several of his adult sons and their families, a son-in-law who was a clerk, and his bookkeeper and his wife. John Wilson, a Black laborer who worked for Powell, also resided there alongside a few domestic “mulatto” servants.[63] The 1870 census also indicates that Thomas Doron continued to work as a cabinetmaker and his brother William as a boot maker, with both residing in the household of William Wilson in the city’s Third Ward.[64]

After a long illness requiring medication and assisted living, Budd Doron died 23 October 1872 and was buried in Montgomery’s Oakwood Cemetery. Budd had left no will but died with assets.[65] Upon his death, his brother Charles, despite continuing to reside in New Jersey, bought Budd’s share of the business and renamed the real estate company Charles S. Doron and Company.[66] The complexity of untangling the company’s investments resulted in Budd’s probate not being concluded until 5 February 1876.[67] Thomas, who handled the probate, kept meticulous records. Under “Accounts of Rents and Interests” he listed two significant entries that show that the Dorons had become landlords to John W. Powell, John Powell Jr.’s eldest son:

Rented Shops & House on Adams St. to

John W. Powell & Co. for one Year Oct 1st 1872 $1700.00. . .

Rented Shops to JW Powell & Co. from

Oct 1st 1873 one Year $1100.00. . .[68]

In 1877 Powell, Prickett & Co. dissolved their partnership. Although John Powell died the following year, some of his sons continued working in the furniture business. [69] His twins, William and Wesley, appeared in the 1878 Montgomery city directory as W.W. Powell & Brothers, furniture dealers and undertakers, and John’s eldest son, John W. Powell, was in a business called Powell & Price, manufacturers of and dealers in carriages, buggies, wagons, etc.[70]

Philanthropy

The perspective map of Montgomery printed in 1887 (Figure 23) conveys a picture of the city that suggests that life was returning to a new normal by the 1880s. In the image, smoke billows from the chimney stacks of the plants in the industrial area by the waterfront. Although three steamboats navigate the river, at least a dozen trains chug along the many tracks encircling the town, suggesting that, by the 1880s, railroads had surpassed river transportation.

As the city was undergoing a period of transformation, so too was Thomas Doron. At this point in his life, Doron had changed careers. He was no longer an active cabinetmaker and instead took on administrative and philanthropic roles in the city. In the 1880 city directory, Thomas was listed as the Secretary and Treasurer for the Mechanics Hook and Ladder Company No. 1.[71] In 1878, the city transitioned from a volunteer service to paid officers, and the fire department developed a more efficient infrastructure.[72] The Capital City Water Company built a new pump station with hydrants throughout downtown, a telephone system permitted a rapid alarm and response time, and horse-drawn steam pump fire engines and hoses replaced the old bucket brigades. Each May, the various fire stations competed in lavish parades for grand prizes up to $1000. The Mechanics Hook and Ladder Company No. 1 hosted an annual picnic considered one of the biggest and best in the state, and during his time with the fire company, Doron became well-known as a talented cook and master of the pit.[73] The local paper explained that Doron was an “experienced caterer… at the head of the arrangement committee, and is sparing neither money nor pains, to make it a success.”[74] The company created a very close-knit group of men, proud of their organization and devoted to the city.[75]

In addition to his role with the Mechanics Hook and Ladder Company, in 1883 Doron served as the Treasurer for the Montgomery Lodge No. 6 of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows and was the Tiler for the St. Paul’s Encampment No. 2, a smaller, local group within the organization.[76] A primary goal of the organization was to provide relief for those in distress, and as such, the Odd Fellows provided many kinds of assistance, including burying the dead, educating orphans, and caring for widows. Besides helping others, lodge meetings provided opportunities for members to socialize over dinner and dances. Participation in these various organizations provided some of the social means of recovery from the hardships caused by the Civil War. In his roles as Treasurer and Tiler, Doron would have been an active participant in both the philanthropic and social aspects of the Odd Fellows.

Retirement

In the years after he stopped working as a cabinetmaker, Thomas Doron enjoyed retirement. He was an avid sportsman, a member of a shooting club, and a fishing enthusiast. Numerous newspaper articles and announcements during the 1870s and 1880s indicate how much he loved and cared for the outdoors. For example, in an 1878 newspaper column titled “Alabama News,” it was reported that “salmon which were deposited in the Alabama river about fourteen months ago are growing …When first deposited they were not larger than a pin; but yesterday, Mr. T.S. Doron hauled out a score, the smallest of which was four inches in length. Mr. Doron…sent some specimens to Commissioner Baird at Washington.”[77] Over the course of a couple of decades, he aided the U.S. Commission of Fish and Fisheries in stocking the Alabama River and tributaries with shad, salmon, and carp. He also developed a close relationship with Professor Spencer Fullerton Baird, curator and later Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. Thomas led scouting hunts for various zoological specimens, including birds, snakes, and lizards, and donated Native American artifacts and shells from his private collection to the museum.[78]

In 1880 Thomas, a bachelor, and William, a widower, were living together on the second floor of 16 Market Street, the main thoroughfare connecting Commerce Street and the Alabama River with the State Capitol.[79] George Doron died 20 October 1880 and was buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Montgomery.[80] When William remarried in 1881, Thomas relocated to the side wing at 16 ½ Market Street.[81] While on paper Thomas may have appeared wealthy, most of his assets were tied up in real estate, and he used Lot 37 (516 Jefferson Street) and Lot 38 (522 Jefferson Street) as collateral for the loans he needed to make ends meet.[82] In the fall of 1885, Doron needed work done on these properties, and an outstanding bill by contractors and builders Figh and Williams was later claimed against his estate.[83]

Following this period of financial hardship, Thomas became increasingly ill and died 15 February 1886. Two lengthy obituaries appeared for Thomas S. Doron the following day. The Daily Dispatch lauded his entrepreneurial and philanthropic activities, while the Montgomery Advertiser related an insightful event about his nonpartisan values.[84] During Reconstruction, the Union party offered him any office he wanted if he chose to join them. His response, as remembered in the obituary, was that “I was not a secessionist and have always been and am now a Union man, but will accept of no position which justly estrange me from the kindness and sympathy of my old friends.”[85] Like many other women and men who lived through the Civil War, as this remembrance suggests, Doron was caught between conflicting allegiances and beliefs.

Doron’s funeral was well attended. The president of the Hook and Ladder Company ordered its members to appear in full uniform.[86] Also in the funeral procession were representatives from all the other fire companies and members of the charitable Odd Fellows.[87] Thomas S. Doron was buried on 16 February 1886 at Oakwood Cemetery in Montgomery, next to his brother Budd in the family plot at the top of a hill in the cemetery.[88] Each of their headstones (Figure 24) displays emblems of the lodges to which they belonged.

A complete inventory of Thomas Doron’s estate (Appendix A) suggests that at the time of his death he lived in a small yet comfortably furnished apartment, with dining, living, and bedroom furniture, and equipment for the stable. Thomas may have built much of the furniture, and Budd, the buggy and harness. Two wardrobes and a bureau were included in his inventory. Having not one but two wardrobes and a bureau was unusual for a bachelor. The abundance of furniture suggests that Thomas may have had a lot of heavy clothing such as a great coat, jackets, suits, and other formal wear, plus a fireman uniform, fishing and hunting attire, and several pairs of shoes and boots. His brother George was a tailor, while William made shoes and boots, so Thomas may have had discounts or possibly bartered with his woodworking skills to acquire a number of the pieces in his wardrobe. The cook stove and eight chairs reflect his documented enthusiasm for cooking and entertaining. He also owned a double-barreled gun and a rifle, presumably the ones used on his many hunting trips.

Thomas’ chest filled with woodworking tools is the third item listed in the inventory taken of his home after his death. Cabinetmakers’ tool chests were custom-made, but they typically shared the same dimensions and layout: 3 feet long, 20 to 24 inches wide and deep (Figures 25, 26, and 27).[89] The interiors were usually divided into wells, and the sides could be telescoped for sliding tills and trays. Handles were secured to either side so that two people could carry the chest when it was fully loaded. Such chests reflect the mobile nature and work of a journeyman cabinetmaker.

Thomas Doron never married, and in his will his property was divided among his sisters and brothers as well as their surviving widows and his nephews and nieces.[90] George’s widow inherited the houses on Jefferson Street, which she updated with water and gas connections.[91] From 1886 to 1889, the Doron estate continued to pay insurance and taxes on rental property on Bainbridge and Jefferson streets. The final settlement of the estate was recorded in court on 5 September 1889.[92] William, Thomas’ last surviving brother in Montgomery, bought a tavern in 1887 at 32 ½ Dexter Avenue, which he called Doron’s Gem Saloon.[93] When William died in 1899, he joined his brothers in the family plot at Oakwood Cemetery.[94]

Conclusion

Nineteenth-century Montgomery witnessed drastic economic and political changes that reshaped not only the South but the entire nation. A study of Thomas S. Doron’s life, his time spent as a cabinetmaker, and the various philanthropic pursuits he engaged in later in his life reflects many of the changes that the nation saw in the second half of the nineteenth century. His close ties to his brothers highlight the central role of family networks in business activities, while his migration from New Jersey to Alabama is illustrative of the enclave of craftsmen from New Jersey and other northern states who were drawn to Montgomery in search of opportunity as the city grew.

The surviving furniture attributed to Doron testifies to his skill during a period marked by industrial expansion, civil war, and economic uncertainty. Montgomery cabinetmakers who remained competitive quickly adapted to changing fashions, incorporating machine-sawn veneers and ripple moldings into their designs. Doron’s signed corner cupboard, built of imported mahogany and embellished with decorative veneers, shows that he, like other urban craftsmen, was producing fashionable furniture that distinguished his work from that of rural competitors.

Perhaps with some pride, Thomas S. Doron signed his Gothic corner cupboard. This simple yet vital act permitted the investigation into the life of an ordinary cabinetmaker who lived in extraordinary times. As there are no records that he ever established his own shop, his work was closely tied to John Powell’s long-running Montgomery business and to the collaborative environment of large furniture workshops where northern journeymen, enslaved craftsmen, and local apprentices labored together.

This first look into the life and work of Thomas S. Doron opens an important window into the study of Alabama furniture. His signed corner cupboard anchors his career and provides a benchmark for connecting other surviving examples. More broadly, his story complicates and enriches our understanding of nineteenth-century southern craftsmanship, revealing the interplay of migration, family, labor, and design in shaping the region’s cabinetmaking traditions. Further research into his career, whether tracing his time in Cuba, exploring workshop networks, or reassessing other Montgomery furniture, promises to further illuminate not only Doron and his work but also the larger world of furniture production in the South.

Trained at Colonial Williamsburg, Christopher Lang is a traditional cabinetmaker, independent scholar, and a member of the Alabama Road Scholars Speakers Bureau, part of the Alabama Humanities Alliance. He can be reached at [email protected].

The author would like to thank several people for their assistance with this project: Emily and Jack Burwell of the Doris Burwell Foundation; Carole Ann King, the Historic Properties Curator of the Landmarks Foundation in Old Alabama Town; Anne Tidmore, Director of the First White House of the Confederacy; Stephanie Timberlake, Curator of Burritt on the Mountain; as well as the Powell family and extended family members, especially Glen Beckwith; and finally, my family, including Beryl Watkins, Joseph W. Lang, and Sharon Watkins Lang who assisted in research and proof reading.

APPENDIX A: Probate Inventory of Apartment Belonging to Thomas S. Doron

1 Wardrobe

1 Wardrobe

1 Chest Tools

1 Table

1 Stove, cooking

1 Boxes & contents

1 D. B. [Double Barrel] Gun

1 Rifle

1 Arm Chair

1 Sett [sic] Harness

1 Wash Stand

2 Small Tables

1 Mirror

1 Bureau

1 Stove, heating

8 Chairs

1 Bedstead & Mattress

1 Buggy

[1] A uniform pattern of wood veneer across the front of the cupboard obscures the drawer opening. This corner cupboard descended through a family who lived in Montgomery, Alabama before being sold to an antiques dealer in New York City in 1961. Eventually Robert Hicks, an antiques expert and historian from Tennessee, acquired the piece and sold it to the Doris Burwell Foundation of Huntsville who returned the cupboard home to Alabama at the Burritt Museum. Corner Cupboard signed by Thomas S. Doron, Montgomery, AL, 1852, collection of Burritt on the Mountain, 2001.36.

[2] Ancestry.com, “Alabama, U.S., Marriages, Deaths, Wills, Court, and Other Records, 1784-1920,” Thomas S. Doron. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1898/records/181025 (accessed 1 May 2025); Family Search, “New Jersey Death and Burials, 1720-1988.” Online: https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FZ8Q-2MK (accessed 14 October 2013). Thomas Stacy Doron’s name appears in the entry for Joseph Doron, 1785.

[3] H. Stanley Craig, Burlington County, New Jersey Marriages (Woodbury, NJ: Glouster County Historical Society, 1977), 66; Ancestry.com, “Thomas S. Doron Genealogical Records.” Online: https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/67334123/person/232141200122/ (accessed 2 January 2025); Ancestry.com, “New Jersey Marriage Records, 1670-1965.” Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/61376/records/209702 (accessed 2 January 2025); Ancestry.com, “St. Andrew’s, 1786-1859, Parish Register, Vol. 1,” Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey; Trenton, NJ. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/62073/records/258612 (accessed 2 January 2025).

[4] Charles S. Doron remained in Burlington County, New Jersey, marrying Sarah Ann Bell in 1847, and served as a tax collector in 1867. Major E. M. Woodward, History of Burlington County, New Jersey (Philadelphia: Everts and Peck, 1883), 284.

[5] Thomas’ older brother John B. Doron (ca. 1819-1898), a blacksmith, moved to Xenia, Ohio, and married Diadem Rice in 1846. Gazette News-Current, Xenia, Ohio, 8 January 1898; Find a Grave, “Gravestone for John B. Doron, Woodland Cemetery, Xenia, Greene County, OH.” Online: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/178650332/john_b_doron (accessed 2 January 2025). His younger sister Sarah Ann Doron (1821-1869) married Joseph Powell in 1838 and moved to Warren County, Ohio. After his death, she married Joshua Norcross in 1858. Alonzo Norcross, Marguerite Norcross Hoke, and Virginia Norcross Toner, The Norcross Family of New Jersey, ed. Mary Elma Easlick Eckert (Woodbury, NJ: Gloucester County Historical Society, 1997), 62-63. Thomas also had a half-sister, Eliza Frazer Smith, who stayed in Mount Holly, New Jersey, and a half-brother, Benjamin Frazer, who moved to South Bend, Indiana. In the settlement of the estate of B. W. Doron, Benjamin Frazer is listed as a half-brother living in South Bend Indiana in 1876, and Eliza Smith, deceased, was listed as a half-sister. All the siblings were important because they and their offspring are mentioned and receive inheritance from Thomas’ last will. Ancestry.com, Alabama, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1753-1999, Montgomery County, Alabama Estate Case Files, Doron, Budd W, Image 1372. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8799/records/4507141 (accessed 28 April 2025).

[6] Ancestry.com, “New Jersey, Deaths and Burials Index, 1798-1971;” 1850 Federal Census, Mount Holly, Burlington County, New Jersey, 420B.

[7] Ancestry.com, “Pennsylvania, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1798-1962.” Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8769/records/10550709 (accessed 6 January 2025); Advertiser and Register, Mobile, 15 February 1845. This advertisement specifies that “The coppered and copper fastened brig IMPORTER, Capt. Marsh [carried] freight or passage;” The Charleston Mercury, Charleston, 27 November 1843. This advertisement lists goods imported at Charleston from the Importer, which included “Hay 100 bales, Bricks 60,000, Lumber 10,000 feet.”

[8] Ad Bowett, Woods in British Furniture-Making, 1400-1900: An Illustrated Historical Dictionary (London: Oblong Creative Ltd., 2012), 135; Jennifer L. Anderson, Mahogany: The Costs of Luxury in Early America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 200-201, 286.

[9] In the 1860 census William is listed as living in the same household as his brother George who already had a young family. 1860 Federal Census, Montgomery, Alabama, District 1, 169. In the 1855 census William is also listed as living in Montgomery. 1855 Alabama Census, Montgomery, Alabama, 57. William’s obituary, The Weekly Advertiser, Montgomery, 10 February 1899; Budd W. Doron’s estate administration, Ancestry.com, Administration Record, Vol. A, 1870-1885, Montgomery, Alabama, 62-63. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8799/records/3460169 (accessed 6 January 2025.); Lydia King Doron marriage announcement, New Jersey Mirror, 20 August 1857; obituary, Montgomery Advertiser, 12 January 1908.

[10] Several plank roads were built through the swamps of Montgomery in the mid-nineteenth century including the South Plank Road and the Central Plank Road. A description of Macon County written in 1852 discusses the development of these new roads, stating: “Let us turn our attention to improving everything about and around us; let us build plank roads; let us make all our public highways of pleasantness.” The Alabama Journal, Montgomery, 17 April 1852.

[11] Christopher D. Haveman, “The Removal of the Creek Indians from the Southeast, 1825-1838,” (Ph.D. dissertation, Auburn University, 2009), 354.

[12] The first State Capitol building, constructed in 1847, burned down in 1849. The current structure was built on the original foundations and completed in 1851. Douglass C. North, The Economic Growth of the United States, 1790- 1860 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1966), 122-134. Society of Pioneers of Montgomery, Pioneers Past & Present 1855-2001: the Society of Pioneers of Montgomery & their Ancestors (Montgomery, AL: The Society, 2001).

[13] Clanton W. Williams, “Early Ante-Bellum Montgomery: A Black-Belt Constituency,” Journal of Southern History 7, no. 4 (November 1941): 510.

[14] Christopher Lang, “Hugh Easley, Alabama Cabinetmaker,” The Magazine Antiques CLXI, No. 5 (May 2002). This article discusses early cabinetmaking in the Huntsville area. Lang argues that conditions for the furniture trade in Montgomery functioned differently from those in North Alabama, which was more isolated from outside competition.

[15] Search by birthplace for 1850 and 1860 Montgomery County, Alabama census records completed on 22 August 2025. Ancestry.com.

[16] Ken Schwemmer, “A Brief History of Manufacturing in New Jersey From Colonial to Modern Eras, Part I,” New Jersey Manufacturing Extension Program Blog, 3 November 2022. Online: https://www.njmep.org/blog/a-brief-history-of-manufacturing-in-new-jersey-from-the-colonial-to-modern-eras/ (accessed 24 April 2025); Seth Rockman, Plantation Goods: A Material History of American Slavery (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2024).

[17] Society of Pioneers of Montgomery, Pioneers Past & Present 1855-2001: the Society of Pioneers of Montgomery & their Ancestors (Montgomery, AL: The Society, 2001), 202-204.

[18] Hon. Joel C. DuBose, ed., Notable Men of Alabama: Personal and Genealogical With Portraits (Spartanburg, SC: The Reprint Company, 1976), 87.

[19] Alabama Journal, Montgomery, 29 Jan 1840.

[20] Alabama Journal, Montgomery, 4 May 1842.

[21] E. Bryding Adams, in her essay “Mortised, Tenoned and Screwed Together: A Large Assortment of Alabama Furniture” Adams provides an overview of cabinetmaking activities in Alabama and discusses the major furniture centers in the state, which included Montgomery. Doron is not included in this study. E. Bryding Adams, Made in Alabama: A State Legacy (Birmingham: Birmingham Museum of Art, 1995), 190-237.

[22] For instance, in the decades following the dissolution of his partnership with Dickerson Powell resumed carriage work, undertaking, and furniture repair.

[23]1850 Federal Census, Montgomery Ward 1, Montgomery, Alabama; Roll: M432.12, page 126A; Image 117.

[24] Uncovering the mystery of this cabinetmaker is further compounded by the frequent misspelling of his last name. Doron’s name appears in the records in countless ways, including Doran, Doren, Deren, and Down. Deviations in spelling were common, and these types of mistakes occurred regularly on census reports. Even though the first name is listed as David, it is still possible that this is the cabinetmaker Thomas S. Doron as he cannot, as of yet, be located on any other 1850 census and in the 1860 census Thomas S. Doron is listed only a couple of households away from Powell. Additionally, to date, no other men matching “David Deren” from the 1850 census have been found in other records.

[25] Descendants of the Powell family inherited several heirlooms from Powell’s furniture business, though these pieces have been scattered over time. Some of these pieces were recorded in the article “Many Native Antiques Traceable to John Powell” written by Esther R. Dill and published in the Montgomery Advertiser on 14 September 1941. For example, one of the pieces passed through the family was a fine music cabinet made of rosewood with a mirror on a square door framed with beaded molding that had a base which consisted of lyres on either side with a cross stretcher. Peter A. Brannon, who between 1910 and 1967 held several positions at the Alabama Department of Archives and History including Curator, Archivist, and Director, during the urban renewal of downtown Montgomery was able to acquire several interesting local pieces for his private furniture collection. This included a walnut plantation desk and bookcase on turned legs and a walnut spool bed with low posts. As a columnist for the Montgomery Advertiser, Brannon mentioned in the article “Rawhide Bottom Chairs,” published 27 January 1935, that “Powell made Bookcases, Cottage bedsteads, mounted Pier mirrors, … and fine Spool beds ….” Brannon also owned several pine tables which he claimed were made by enslaved labor. Ancestry.com Message from Glen Beckwith to author regarding Powell at Perry Street, 8 March 2014.

[26] 1850 Federal Census Slave Schedules, Montgomery Ward 1; 1860 Federal Census Slave Schedules, Montgomery District 1.

[27] John S. Bowman, American Furniture (Greenwich, CT: Brompton Books Corp, 1985), 100.

[28] In their discussion of construction, the authors devote over eight pages to the subject of veneering. Given his chosen working style, it is likely that Doron would have found the sections on geometry and ellipses very appealing.

The Cabinet-Maker’s Assistant: A Series of Original Designs for Modern Furniture, with Descriptions and Details of Construction, (originally published in 1853 by Blackie and Son’s, reproduced by Andesite Press, 2017).

[29] It is likely that the interior stain was added as part of the 1935 repair work noted by James Hassel as finished interiors are a twentieth century, rather than a nineteenth century, aesthetic. Also, in a descriptive note by Robert Hicks given to Jackson Burwell about the Corner China Cupboard he states that the 1935 repair was the last finish applied. Accession file for Corner Cupboard signed by Thomas S. Doron, Montgomery, AL, 1852, collection of Burritt on the Mountain, 2001.36.

[30] Joseph Moxon, Mechanick Exercises (London, 1679), 103, first recorded a “waving engine” (Figure 5.7) used in Dutch frames. The wavy molding was revived in the 1840s as part of the Gothic style. Thomas H. Ormsbee, Field Guide to American Furniture (New York: Bonanza Books, 1952), xxxi.

[31] The piece was appraised in June 2001 by Edward Pattillo, an antiques and fine arts consultant in Montgomery. He drew general comparisons between the two corner cupboards and attributed the work to Thomas Doron. Accession Records, Corner Cupboard 2003.009.001, Landmarks Foundation of Montgomery (hereafter LFM).

[32] For this comparison, I used the Alabama Decorative Arts Survey data form created for the Birmingham Museum of Art, which has a 17-point analysis of drawer construction. Using the drawer construction data sheets, the points of similarity between the drawers of the two corner cupboards are the following: 1) Drawers are located bottom center. 2) Medium size. 3) Fronts of drawers ¾ inch thick with mahogany veneer. 4) Front edge treatment is plain. 5) One board bottom is parallel to front. 6) Front and sides fit into dado groove. 7) Sides beveled to fit dado. 8) No glue blocks used. 9) Runners are bottom edge of drawer sides. 10) N/A. 11) Front corners are dovetailed, shape has the same splay with tight fit. 12) Top edges are flat. 13) Outer surfaces are planed, though the bottom side is rough. 14) Inner surfaces are all planed. 15) Bottom to back fastener is a wrought nail. 16) No pull, key in escutcheon. 17) Locks are mortised in and attached with screws. The Alabama Decorative Arts Survey database and forms can be viewed at www.bplonline.org/ADAS.

[33] Accession Records, Corner Cupboard 2003.009.001, LFM.

[34] Cameron Freeman Napier, The First White House of the Confederacy (Montgomery: The First White House Association, 1930). This guidebook provides a succinct yet informative history of Jefferson Davis and the house and its contents, many of which belonged to the Davis family.

[35] Edward Pattillo, “Watts pair of bookcases Acc. 237, 238,” First White House Appraisal, 99-100. Pattillo’s appraisal provides a general description of the bookcases as well as provenance information which attributes them to Thomas Doron and states that they are exceptionally rare. The pieces were given to the First White House by Elizabeth Thigpen Hill, a descendant of Governor Watts.

[36] The attribution of the bookcases to Doron was made during an appraisal of the entire collection in 2010.

Edward Pattillo, “Watts pair of bookcases Acc. 237, 238,” First White House Appraisal, 99-100.

[37] Several wealthy Montgomery families had townhouses in the city and summerhouses in the country where they retreated from the heat and disease of the city. Other gentlemen would commute by railway to the city for work and return on weekends to the suburbs, including the villages of Verbena and Mountain Creek, which began developing in the mid-nineteenth century within a thirty-mile radius of downtown. In her annotated and edited volume of Matthew Blue’s brief history of Montgomery, Neely provides many keen insights into the region, including discussion of the “getaway” communities that sprang up around the city in the nineteenth century. Mary Ann Neely, ed., The Works of Matthew Blue, Montgomery’s First Historian (Montgomery: New South Books, 2010).

[38] Bowman, American Furniture, 100, 102.

[39] The Montgomery Advertiser, 30 April 1851.

[40] American Cotton Planter, Montgomery, AL, 1 September 1853. Online: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044056238975&seq=106 (accessed 24 April 2025).

[41] While the wedges made disassembly and reassembly simple, over time the joints loosened, leaving the wardrobe somewhat unstable.

[42] The Alabama Journal, Montgomery, 17 April 1852.

[43] Correspondence and lab identification from the Center for Wood Anatomy Research of U.S. Forest Products in Madison, Wisconsin, Accession records for Howard Wardrobe 1973.009.001, LFM.

[44] Correspondence between Milo B. Howard, Jr., Director State of Alabama Department of Archives and History and James L. Loeb, Founder of Landmarks Foundation of Montgomery, 10 December 1979, Accession Records for Howard Wardrobe, LFM.

[45] Probate Court, Conveyance Records, Old Series, Montgomery County, 1817-1869, 8:135.

[46] The Montgomery Directory for 1859-1860 (Montgomery, AL: Advertiser Book and Job Printing Office, 1859), 35.

[47] Policies included Insurance companies from Mobile, Georgia Home, Sun Mutual of New Orleans, Norwich Union in New York, Western Assurance of Toronto, Canada. Four properties are described as one- or two-story frame dwellings rented to tenants and are all listed on Thomas Doron’s estate. Ancestry.com, Alabama, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1753-1999, Montgomery County, Alabama Estate Case Files, Doron, Thomas S, Image 1794. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8799/records/4508173 (accessed 28 April 2025). The threat of fire in a cabinet shop with all the wood and sawdust was a real hazard. In 1855, John Powell’s shop burned down. Richard Williams Powell, Powell’s grandson, wrote in a family account that “… there was a well a few doors up the street, but the owner did not like Mr. Powell and would not let the men get water there for fighting the fire.” The unsympathetic owner of the well was Thomas Welch, the Postmaster of Montgomery. Glen Beckwith, e-mail message to Beryl Watkins, 8 March 2014; “The Origin of the Confederate Post Office Department and Comments on Some Stamps,” Alabama Historical Quarterly 20, no. 1 (1958): 65. In addition to purchasing insurance, Thomas and his brother quite literally took matters into their own hands and became members of the Mechanics Hook and Ladder Company No 1, a local fire department.

[48] This report details the Doron real estate partnership and includes a description of the location of properties on Adams and Perry Street. Ancestry.com, “Probate Court, Report of sale filed 11 November 1875,” C. W. Burkley Judge, Montgomery County, AL, Book F, page 409. Bud Doron estate file. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8799/records/4507141 (image 1380, 1388, 1420).

[49] Probate Court, Conveyance Records, Old Series, Montgomery County, AL, 1817-1869, 12. Note 1 $2600, Note 2 $2700; Montgomery Advertiser, Montgomery, AL, 26 August 1888.

[50] This was one of several homes developed by the brothers during this period.

[51] The Watts Mansion was incorporated into St. Margaret Hospital in 1902. Troy University, “Historical Buildings of Montgomery, Alabama, as displayed through the Traveling Exhibits.” Online: https://www.troy.edu/libraries/wade-hall-postcards/traveling-exhibit/historical-buildings/index.html (accessed 25 April 2025).

[52] 1860 Federal Census, District 1, Montgomery, Alabama, Roll: M653.19, Page 169, Image 169, Family History Library Film: 803019.

[53] 1860 Federal Census, District 1, Montgomery, Alabama, Roll: M653.19, Page 173, Image 173, Family History Library Film: 803019.

[54] In the 1850 census Samuel C. Prickett, age 12, is listed as living with his grandfather Thomas Middleton. 1850 Federal Census, Mount Holly Burlington, New Jersey, Roll: 444, Page 414B, Image 265. By 1860 Samuel C. Prickett is recorded as having moved to Montgomery. 1860 Federal Census, District 1, Montgomery, Alabama, Roll M653 19, Page 169, Image 169, Family History Library Film: 803019.

[55] For discussion of Montgomery’s architectural heritage and a glimpse of how the city appeared when the Doron brothers were working in the city, including discussion of how the houses they built may have resembled the historic “Four Sisters,” located on South Perry Street which were noted for their fine quality craftsmanship, see: Jeffrey C. Benton, A Sense of Place: Montgomery’s Architectural Heritage 1821-1951 (Montgomery: River City Publishing, 2001).

[56] For a chronological history of how Montgomery contributed to the Civil War and describes how the war impacted the city and its residents see: William Warren Rogers Jr., Confederate Home Front: Montgomery during the Civil War (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 1999).

[57] Rogers Jr., Confederate Home Front, 31-32.

[58] Bill of Sale, B. W. Doron to Confederate States, 30 September 1862, US, Confederate Citizens File, 1861-1865 Online https://www.fold3.com/file/43551145 (accessed 28 April 2025). Wagon supplies totaling $20.

[59] For a portrait of the gradual demise of the Old South see: Bruce Levine, The Fall of the House of Dixie (New York: Random House, 2013).

[60] Montgomery Journal, 22 October 1916.

[61] For an overview of the economic and social aspects of Reconstruction see: Eric Foner and John A Garraty, eds., The Reader’s Companion to American History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1991), 921-924.

[62] Foner and Garraty, eds, The Readers Companion to American History, 923.

[63] It is possible that some of the free persons of color living in Powell’s household in 1870 were once held in bondage by him, as he is recorded as an enslaver of seventeen individuals (with six “Slave houses”) in the 1860 United States Federal Census Slave Schedules, Montgomery District 1, Montgomery Alabama, 16. 1870 Federal Census, Montgomery Ward 2, Montgomery, Alabama, Roll: M593 35, Page 449A, Image 69, Family History Library, Film: 545534.

[64] In the 1870 census the Doron family name is misspelled as “Down.” 1870 Federal Census, Montgomery Ward 3, Montgomery, Alabama, Roll: 593.35, Page 476B, Image 124, Family History Library, Film: 545534.

[65] Despite the economic issues caused by the Civil War, Budd seems to have weathered the storm as the 1870 census recorded Budd’s real estate at $10,000 and his personal worth was recorded as being $200.

[66] Probate Court, Report of sale filed 11 November 1875, C. W. Burkley Judge, Montgomery County, AL, Book F, 409.

[67] Ancestry.com, Final Statement and Slate of Heirs of the Estate of B. W. Doron, 5 February 1876, Thomas S. Doron Administrator, C.W. Buckley Judge Probate Court. Recorded in Record T, Page 444, Lists all the brothers, sisters, half-brother, half-sister and their children. Also filed, a running account of Rents, Interests, Expenditures, and Net Profits from October 1872 through January 1876, Alabama, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1753-1999, Montgomery County, Alabama Estate Case Files, Doron, Budd W. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8799/records/4507141 (accessed 28 April 2025).

[68] Alabama, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1753-1999. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8799/records/4507141 (accessed 28 April 2025).

[69] John Powell’s obituary, which appeared in the Montgomery Advertiser dated 13 August 1878, read, “Mr. John Powell, who died in this city last Friday, was born in 1796 and was consequently 82 years old. He lived here 54 years, having moved to Montgomery in the year 1824. He was the oldest living inhabitant and enjoyed the universal respect and esteem of all in this community.” The Montgomery Advertiser, 13 August 1878.

[70]City Directory…of Mongomery (Montgomery, AL: T.C. Bingham, 1878), 110, 175. Advertisement appeared for Powell & Price.

[71] The Montgomery City Directory for 1880-81 (Montgomery, AL: Ross A. Smith, 1881), 236.

[72] For the history of the Montgomery Fire Department from its founding in 1817 to 1978 see: Montgomery Fire Department, Montgomery, Alabama, Cradle of the Confederacy (Montgomery: Montgomery Fire Department, 1978).

[73] Describing the history of the department and the city in the 1880s, the authors note that parades were to Montgomery what Mardi Gras was to New Orleans and Mobile. The annual grand picnic was held at Jackson Lake, Elmore County and lasted from 8am to 7pm with a chartered train service. Montgomery Fire Department.

[74] In a description for an outdoors picnic event, Doron is referred to as an “old reliable” who will prepare a feast sparing no expense or trouble. The Montgomery Advertiser, 28 April 1877; The Montgomery Advertiser, 26 May 1880.

[75] In the 1880 Federal Census Thomas Doron’s occupation is listed as a mechanic, a term which included a variety of occupations. 1880 Federal Census, Montgomery, Alabama, Roll: 26, Page 117C, Enumeration District 128, Image 0235, Family History Film: 1254026.

[76] The Montgomery Advertiser, 15 July 1883. A Tiler is the doorkeeper at a fraternal lodge. The Odd Fellows Hall was located at the hub of the business and entertainment districts at the intersection of Montgomery’s Market, Court, and Commerce streets. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows, a mutual insurance fraternity, was established in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1819 when the city was hit by a major yellow fever epidemic. Theo. A. Ross, The History and Manual of Odd Fellowship (New York: The M. W. Hazen Co., 1900), 11; “History of American Odd Fellowship.” Online: https://www/odd-fellows.org/history/wildeys-odd-fellowship/ (accessed 28 April 2025).

[77] The North Alabamian, Tuscumbia, Alabama, 12 July 1878.

[78] Choctaw County News, Butler, Alabama, 21 July 1876. The Museum Support Center, the off-site conservation and collections storage facility for the National Museum of Natural History located in Suitland, MD, has many jars of fish and snake specimens dating back the nineteenth century.

[79] Market Street was renamed Dexter Street in 1884. The Montgomery City Directory for 1880-81 (Montgomery, AL: Ross A. Smith, 1881), 60.

[80] Ancestry.com, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Subject Files, “Doran, George R.” Alabama, US, Marriages, Deaths, Wills, Court and Other Records, 1784-1920. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1898/records/181020 (accessed 28 April 2025); “Record of Internments, 1876-1892,” City of Montgomery, Alabama Oakwood Cemetery. George is buried in Lot 9, Square 10. His wife, Lydia, continued to operate a millinery and dressmaking shop in the city at 2 Perry Street. Montgomery Daily Advertiser, 2 October 1881; 15 January 1869.

[81] Around this time, William turned from boot making to bartending at Young’s Restaurant. The Montgomery Advertiser, 15 March 1881. Ancestry.com, Montgomery, Alabama Directories, 1880-95.

[82] Thomas borrowed $800 from the Mechanics Hook & Ladder Co. No. 1 on 13 April 1885, securing this loan with Lot 37. Ancestry.com, Alabama, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1753-1999, Montgomery County, Alabama Estate Case Files, Doron, Thomas S, Image 1794. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8799/records/4508173 (accessed 28 April 2025).

[83] Alabama, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1753-1999, Image 1800. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8799/records/4508173 (accessed 28 April 2025).

[84] The Daily Dispatch, Montgomery, Alabama, 16 February 1886; The Montgomery Advertiser, 16 February 1886.

[85] From the numerous people in attendance at his funeral it is clear that he was well respected by his peers. On a personal note, his obituary notes that he was very attached to his pet dog, Old Frank, his companion of sixteen years. Obituary of Thomas S. Doron, The Montgomery Advertiser, 16 February 1886.

[86] The Daily Dispatch, Montgomery, Alabama, 16 February 1886.

[87] The Daily Dispatch, Montgomery, Alabama, 17 February 1886.

[88] The Doron family plot was situated at Lot 9, Square 10.

[89] Jim Tolpin, The Toolbox Book (Newtown, CT: Taunton Press, 1995), 13.

[90] Record of Wills, Vol. 5, Montgomery County, AL, 536-539.

[91] Ancestry.com, Alabama, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1753-1999, Montgomery County, Alabama Estate Case Files, Doron, Thomas S, Image 1794. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8799/records/4508173 (accessed 28 April 2025); John H. Engelhardt, Water works Gas Fitting, Bill for $14.55.

[92] Ibid., Final Settlement, 5 September 1889, Francis C. Randolph Judge Probate Court.

[93] William Doron advertised “Doron’s Gem Saloon the best wines Liquors and Cigars, free lunches every day.” City Directory of Montgomery 1898, 266.

[94] His wife, Belle May, and their surviving children returned to Baltimore, Maryland, her family home. In 1910 Belle M Doron and her three children are recorded in her father Thomas A Murphy’s household. 1910 United States Federal Census, Baltimore, Maryland, Ward 17, District 0295.