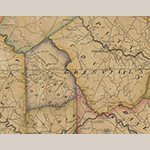

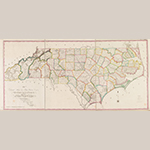

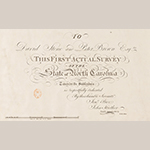

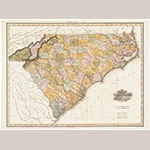

Over two centuries have passed since Jonathan Price and John Strother published their noteworthy map of North Carolina (Figure 1). The Price-Strother map is significant for a number of reasons, but foremost because it was the first map of the state of North Carolina that was drawn from an actual survey. Unfortunately, the map’s importance has largely been overlooked by scholars and historians since its creation. Indeed, a scant fourteen years after the map was published, Jonathan Price’s eulogist observed: “It is believed that neither the public utility and vast importance of the [map], nor the difficulty in executing it, have ever been reflected on by one in a thousand.”[1] Those words would prove to be prescient. In the ensuing two hundred years since the map was released, very few scholars have “reflected on” Price and Strother’s remarkable achievement that was more than fifteen years in the making.

The first published article devoted to the Price-Strother map was Fred Olds’s 1926 article in The Orphans’ Friend and Masonic Journal.[2] It would be another thirty-eight years until a second would be written: Mary Lindsey Thornton’s seminal 1964 article about the map in North Carolina Historical Review.[3] Very little, if any, new scholarship has been published about the map since Thornton’s article. In recent years, however, new information about the map and its creators has come to light. By revisiting the documentary record and reconsidering historical context, it is hoped that this article will firmly establish the monumental importance of the Price-Strother map within North Carolina’s cartographic history.

The Price-Strother map of North Carolina was created during a critical time of westward expansion in the state with changing political boundaries and a dramatic increase in population. The sheer scale of North Carolina’s geographic growth in the late-eighteenth century directly influenced the development of the map. It is likely that Price and Strother individually surveyed different parts of the state. It seems that Price surveyed the eastern counties and Strother focused on the Piedmont and western counties.

Published nearly simultaneously with the 1807 Bishop Madison map of Virginia, the Price-Strother map preceded the 1818 Sturges-Early map of Georgia and Munsell map of Kentucky by a decade; the 1822 John Wilson map of South Carolina by at least fourteen years; and the 1832 Matthew Rhea map of Tennessee by at least twenty-four years. The map served as the foundation for subsequent great nineteenth-century maps of North Carolina, including the 1833 MacRae-Brazier map and its derivatives and the 1857 Cooke map. At the time of its publication, the Price-Strother map of North Carolina was easily the most accurate map of North Carolina yet produced.

Cartographic & Historic Context of the Map

Why has a map of such great importance to the state’s cartographic history received such scant attention? Perhaps the primary reason is that there is equally little information pertaining to the map in extant records.

One can reasonably assume that the lack of an accurate map of North Carolina in the years following the War for Independence was a fact known to many of the state’s citizens. How many citizens were there at the onset of the war? Unfortunately, there are no census records for North Carolina from the colonial era, but H. Roy Merrens estimated North Carolina’s population based on taxables at 65,000 to 75,000 in 1750 and 175,000 to 185,000 in 1770.[4] North Carolina experienced dramatic population growth in the last half of the eighteenth century. By 1800, the Federal Census counted just fewer than 400,000 residents in the state. Much of this population boom occurred in the Piedmont, as confirmed in a February 1756 letter to Philip Ludwell written by Rev. James Maury of Louisa County, Virginia:

By Bedford Court-house in one week, ’tis said, &, I believe, truly said, near 300 Persons, Inhabitants of this, Colony, past, on their way to Carolina. And I have it from good Authors, that no later in Autumn than October, 5000 more had crossed James River, only at one Ferry, that at Goochland Court-house, journeying towards the same place: &, doubtless, great Numbers have past that way since.[5]

A decade later, the population boom continued, as recorded in a 1767 Connecticut newspaper:

Williamsburg (Virginia) October 8

…There is scarce any history, either ancient or modern, which affords an account of such a rapid and sudden increase of inhabitants in a back frontier country, as that of North Carolina. To justify the truth of this observation, we need only to inform our readers, that twenty years ago there were not twenty taxable persons within the limits of the…County of Orange; in which there now are four thousand taxable. The increase of inhabitants, and flourishing state of the other adjoining back counties, are no less surprising and astonishing.[6]

This steady influx of settlers to the North Carolina Piedmont received woefully inadequate cartographic attention. Prior to the Price-Strother map, the most recently published map of North Carolina based at least in part on surveys was the 1770 Collet map (Figure 2).[7] The Collet manuscript was completed in 1768, so the published map did not show Tryon County (established in 1768), any of the four counties demarcated in the Piedmont in 1770, or any county borders. In a short span of six years (1774-1779) no fewer than sixteen new counties were created in the state. Those counties existed by law but not by map, presenting great difficulties for those trying to locate land grants or identify other important features for commerce and trade on a map that was lacking the basic political boundaries within the state.

Little effort seems to have been made by those in power during the last quarter of the eighteenth century to overcome the deficiency in North Carolina’s geographical knowledge. The lack of progress to develop a new map was likely due to the general poverty of the new state in the decades immediately following the American Revolution—even so, the absence in state records of any mention of the need for a revised new map is discouraging. The North Carolina General Assembly finally considered the subject of sponsoring a map in 1790. On 7 December, Senator Joseph Graham of Mecklenburg County presented “A Bill for obtaining an accurate Map of the State.” The bill was read once in the Senate and referred to the House, where receipt thereof was acknowledged the same day. On 10 December, the House “Ordered, That the bill for obtaining an accurate map of the State, be laid over until the next Assembly.”[8] There is no record of the bill being reintroduced at the 1791 General Assembly.

Jonathan Price and the Development of the Map

The need for an accurate map of North Carolina did not escape the notice of Jonathan Price.[9] Although it is not known when or where Price was born, his father, Benjamin Price, moved the family to Pasquotank County in the late 1770s.[10] In 1781, Jonathan requested to come under care of the Pasquotank (Symons Creek) Monthly Meeting of Friends and was received as a member in 1785.[11] He married Susannah Morris in 1786 at a Quaker Meeting near Newbegun Creek.[12] The couple had three children: Mary, who died as an infant; Miriam, who died in 1813 at age 23; and Samuel, born on 3 January 1792.[13]

Price and his family, including siblings, were active in the Pasquotank (Symons Creek) Meeting, but he and his brother William did not seem to agree with all of the Quaker principles. William was disowned, or removed, from the meeting in 1782 for marrying outside of the society and also for not receiving a certificate to allow him to serve in the military. In 1797, Jonathan was removed from the meeting. In contrast, a third Price brother, John, was a long-standing member of the Pasquotank (Symons Creek) Meeting. John was received by request in 1780, married twice within the meeting, and was named an elder in 1795.[14]

According to William Powell’s Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, Jonathan Price taught himself to become a carpenter and his brother John trained as a bricklayer. Jonathan Price’s career as a house carpenter was not long lived. Although he took on Joseph Newby as an apprentice in 1785, no documentation survives after that year for Price working as a carpenter. Instead, he seems to have set out to learn the skills of a surveyor.[15]

Jonathan Price was successful in mastering the skills of the compass and chains. In March 1789, he was appointed surveyor of Pasquotank County.[16] That same year, he began work on a map of the state, as evidenced by a petition presented by Price to the General Assembly on 25 December 1792:

Your Petitioner being sensible to the Great Utility that a correct Map of this State would be to the inhabitants thereof, has for this Three Years past been Labouring at the same [author’s emphasis] on his own expense and now proposes to Lay before this respectable Body what he has already done, and if encouragement is given to go on with the undertaking shewing in an accurate manner on a much larger scale than has ever yet been attempted, by Actual Surveys… and adorned to be finished as Speedy as the Nature of the cost will Admit… .[17]

Not to be outdone, another prospective cartographer, Nathaniel Christmas, presented a similar petition to the General Assembly that same day:

Being well acquainted with the great utility that a General and Correct Map would be to this State as well as for the benefit of the inhabitants thereof… Your petitioner (being a Native of this State)… with the assistance of some Skillful artist, has made some progress therein at his own expense… .[18]

According to Mary Lindsey Thornton, the “Skillful artist” to whom Nathaniel Christmas referred likely was his brother William, an accomplished surveyor who had laid out the new capital town of Raleigh in 1792 and, conveniently, was a member of the State Senate at the time the two petitions were made.[19]

The committee to which the petitions were referred reported back favorably to the General Assembly with a recommendation that the petitioners combine their talents:

The committee to whom was referred the memorial of Nathaniel Christmas and Jonathan Price, report —That they are of opinion that such attempts to procure a correct plan and map of the State, are worthy of receiving the greatest encouragement from the legislature —That the two applicants, from their relative situations, might effect jointly, by comparing their notes, surveys and observations, this subject, with more accuracy than when single —That the pretentions of each are equal, and are equally well recommended in point of character and capacity. —Your committee do therefore submit, that the petitioners be allowed the sum of five pounds for each county, by way of advance, upon their giving security to effect the plan proposed by actual survey, and that they have a copy right in the same when compleated… .[20]

The General Assembly approved the committee’s recommendation on 31 December 1792.[21] The following day, Governor Richard Dobbs Spaight wrote to John Haywood, the state’s public treasurer:

Please pay to Misters Nathaniel Christmas and Jonathan Price

Two Hundred & Ninety pounds Current Money,

being in advance for Maps which they are to deliver… .[22]

As recommended by the committee, the General Assembly allotted only £5 per county survey for each of the fifty-eight counties existing at that time, for a total loan of £290. Even in 1792 currency, completing a survey at a cost of £5 per county seems overly frugal—and it was. In a subsequent petition in 1795, Price reminded the General Assembly that a 1792 joint committee of both Houses had recommended £20 per county (which would have amounted to a loan of £1160).[23] Price also stated that the 1792 Assembly wanted proof that Price and Christmas could actually accomplish such an ambitious project before showing a higher level of generosity. The comments in Price’s 1795 petition suggest that he was privy to a committee discussion that did not find its way into the 1792 legislative documents, including the final manuscript and published committee report.

Price’s and Christmas’s expenses per county survey were on average about £35, or seven times the amount loaned by the legislature, forcing the authors to solicit subscriptions to finance the surveys. The following announcement appeared in the 19 February 1794 issue of the North Carolina Journal published in Halifax, NC:

Nathaniel Christmas and Jonathan Price,

Respectfully inform the public and their friends in general, that they are about the business of making a Map of this State by actual survey — The General Assembly has been pleased to allow the sum of five pounds for the survey of each county, but they find by experience that the above sum will be expended in surveying two and a half days, and that upon an average the survey of each county cannot be made for a less sum than thirty or forty pounds — they therefore must rely on the friends of the undertaking for subscriptions. They are proceeding to finish the surveys of the districts of Edenton and Halifax, which they will publish as soon as completed, with as many of the adjacent counties annexed thereto, as shall make one sheet, containing about one-fourth of the map; and they will attend at the different courts of Halifax district, on the second day of each court, in order to receive subscriptions… they hope the subscribers will be pleased to pay the one half of the sums subscribed, on their finishing the survey of the county in which they reside… .[24]

No list of subscribers is known to survive, nor is there any record of publication of any portion of the map prior to completion of the entire map.

That is the last mention of Nathaniel Christmas as a contributor to the project. He returned to the Georgia Western Territory (now Mississippi) where he had been involved in land speculation in the 1780s and where he likely perceived a better opportunity for financial reward. “After being deserted by Christmas,” Price continued the project with the aid of John Strother.[25]

Strother was born in Culpepper County, Virginia, the son of George Strother and Mary Kennerly.[26] When George Strother died in 1767, he left a provision in his will for his eldest son John to be trained as a surveyor. Sometime after 1785, John Strother moved to Wilkes County, Georgia, ostensibly to survey Indian lands that were then opening to settlement. Nathaniel Christmas and John Strother were both documented in Wilkes County in 1786—therefore, they may have been acquainted. If so, perhaps Christmas encouraged Strother to work with Jonathan Price on the North Carolina map. More likely, Price was recommended to Strother through members of the influential Blount family of North Carolina.[27]

Strother’s introduction to the Blounts probably began through William Blount (Figure 3), governor of the Tennessee Territory. Both Strother and Blount had been involved in an attempt to purchase lands at Muscle Shoals on the Tennessee River. William Blount’s brothers, Thomas Blount and John Gray Blount, had almost certainly also invested in the Muscle Shoals venture. John Gray Blount (Figure 4), in particular, is the strongest candidate to be the individual that brought Strother and Price together. Strother had been acquainted with or employed by John Gray Blount since at least 1785. Jonathan Price also worked for John Gray Blount, from about the time of Nathaniel Christmas’s departure from North Carolina.[28]

The Blount family was involved in land speculation on a massive scale, with John Gray Blount recognized as one of the largest individual landowners in our country’s history.[29] Blount was educated as a surveyor, elected to multiple terms in both the North Carolina House and Senate, served as postmaster of Washington (North Carolina), and held numerous other civic positions, including trustee of the University of North Carolina. But first and foremost, he was a merchant and landowner. John Gray and his two brothers, Thomas (Figure 5) and William, organized the business of John Gray and Thomas Blount, Merchants, in 1783. The brothers built sawmills, grist mills, tanneries, cotton gins, and a distillery. At William’s home, Piney Grove Plantation in Pitt County, they operated a nailery, and produced naval stores and grew corn and tobacco for export.[3] A mercantile store was also opened in Thomas’s hometown of Tarboro, North Carolina.[31]

For exporting their products and importing goods to be sold for profit, the Blounts owned a fleet of four ships and a number of flats.[32] John Gray Blount and John Wallace were partners in Shell Castle (Figure 6), which consisted of a tavern, wharves, warehouses, and a store built on a small oyster shell island just inside Ocracoke Inlet.[33] In addition to trade with other U.S. ports, the Blounts had shipping interests in the West Indies, Britain, and Europe. They used their influence as members of the North Carolina General Assembly to open North Carolina’s western lands to large-scale speculation and funneled profits from their shipping and mercantile businesses into land speculation. David Allison worked in Philadelphia as a seller’s agent for the Blounts, attempting to unload millions of acres of North Carolina land registered in counties that did not exist when the Collet map was published in 1770. A new map of the state would have been very advantageous to the Blounts’ real-estate investments.

Price and Strother’s first collaboration on behalf of the Blounts may have been a survey of Ocracoke Inlet, including the very important Shell Castle. In December 1795, a pamphlet titled A description of Occacock [sic] Inlet…adorned with a map…by Jonathan Price was published in New Bern with a map based on the survey.[34] Although this survey work may have been entirely that of Price and completed prior to John Strother’s arrival, Strother’s comments in a letter to John Gray Blount would suggest otherwise:

I am happy to hear that Mr. Price has got a small part of our business (If I may say our) published, but am sorry to think I am not known in it, but we must know each other better before any part of my Notes is published, If there is any Credit to be derived from the business I all ways flattered myself with haveing [sic] a reciprocal part of it… for I must confess that I do not think my friend Price has dealt with me, with that Injiniousness [sic] that I expected… .[35]

Also in December 1795, Thomas Blount wrote from Philadelphia to his brother, John Gray:

…enclosed is Information to Mr. Price of the terms at which he may get his map of No. Carolina engraved here in the most elegant style & is my opinion he had better determine to accede to them.[36]

Thomas Blount did not indicate with whom he had negotiated; the information that he enclosed may have been forwarded to Price as it is not part of the Blount Papers.

Shortly thereafter, in February 1796, David Allison wrote from Philadelphia to John Gray Blount:

The Plates of Mr. Price is again Mentioned — if they were forwarded I am induced to believe having them engraved would operate against the Interest of Mr. Price if not better executed than the specimen already given — if you persist they must be had.[37]

The “specimen already given” was likely the map of Ocracoke Inlet, printed a few months earlier from an adequate, though certainly not exceptional, copperplate engraving by New Bern silversmith William Johnston. Allison undoubtedly believed that Philadelphia engravers could produce a work of higher quality; John Gray Blount, however, may have wanted Price and Strother’s pending chart of the North Carolina coast engraved locally to expedite its production, hence his request for the plates. Blount’s urgency is indicated in a letter that he wrote to Jonathan Price on 11 May 1797:

I am desirous for yours as well as my own Interest to See the Chart of the Sea Coast Compleated as I want about 20 to Send to the different Ports of Europe to give an idea of the importance of Shell Castle[.] please inform me when they will be compleated.[38]

Price and Strother had secured copyrights for a map of North Carolina and a chart of the state’s coast in the clerk’s office at the District Court of North Carolina in New Bern on 4 March 1796.[39] As required by law, the copyrights were announced in newspapers, such as the one that appeared in the 12 March 1796 issue of North Carolina Gazette (New Bern).[40] The following is the text as it was published (see also Figure 7):[41]

District of North-Carolina.

Be it remembered that on the seventh [sic] day of March in the XXth year of the independence of the United States of America, Jonathan Price and John Strother of the said district, have deposited in this office the title of a map, the right whereof they claim as authors in the words following, to wit: a MAP Of the STATE of NORTH CAROLINA, Agreeable to its present boundaries.

In Conformity to the act of Congress… .

A. NEALE, C.N.C.D.

A notice for copyright of the related chart of the coast ran in the same issue of the North Carolina Gazette:

District of North Carolina.

Be it remembered that on the seventh [sic] day of March in the XXth year of the independence of the United States of America, Jonathan Price and John Strother, of the said district, have deposited in this office the title of a Chart, the right whereof they claim as authors in the words following, to wit: a CHART Of the sea coasts, from Cape Henry to Cape Roman, and of the inlets, sounds, and rivers of North-Carolina, to the towns of Edenton, Washington, Newbern and Wilmington.

In Conformity to the act of Congress…

A. NEALE, C.N.C.D.

No actual map or chart was deposited with the district court clerk—which is not surprising because copyright law applied to intended as well as completed works.

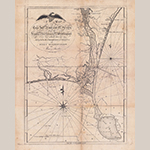

Price and Strother’s efforts on the coast resulted in the 1798 publication of a chart (Figure 8) that, although without a title as indicated in the copyright announcement, did contain the following dedication:

To navigators, this chart being an actual survey of the sea coast and inland navigation from Cape Henry to Cape Roman is most respectfully inscribed by Price & Strother.

This chart was an entirely local production: surveyed and drawn by Price and Strother; engraved and printed in New Bern by William Johnston and Francois Xavier Martin, respectively. To the likely dismay of John Gray Blount, the chart hardly gave an “idea of the importance of Shell Castle,” as its location is not even named.

Published at approximately the same time as their coastal chart was Price and Strother’s A map of Cape Fear River and its vicinity from the Frying Pan Shoals to Wilmington... (Figure 9). This map was engraved by William Barker in Philadelphia, and presumably printed in that city. Price and Strother intended for Barker to engrave the map of North Carolina, as indicated in their letter to the General Assembly on 19 December 1798:

For the use of the General Assembly, we beg your acceptance of a Chart of the Sea coast of North Carolina – from Cape Roman to the Virginia Line – also a map of Cape Fear River and its Vicinity as high as Wilmington – upon a Large Scale – which hath been engraved in Philadelphia by the Artist whom we expect to engrave the map of the State.[42]

Despite their success on the coast, the larger project continued to move slowly and Price and Strother continued to request subscriptions to help finance their work, as shown in this advertisement in the 8 June 1797 issue of Hall’s Wilmington Gazette:

They have been upwards of four years laboriously engaged in making the surveys, and been from time to time encouraged by the legislature; and as the work is nearly finished can now venture to open subscriptions for the same… one half paid at subscribing, the other on delivery of the map.

The legislature’s intermittent encouragement included additional loans of £300 to Price in February 1795 and £500 to Price and Strother in December 1796, both loans in response to additional petitions from the mapmakers.[43] Fortunately, some of the leading citizens of the state came to their aid. In his 14 April 1799 letter to John Gray Blount, Jonathan Price wrote:

Mr Blake Baker, Mr Whyte of Glasgow[,] D. Stone, Governor Davie and Several others, being Desirious of giving us Assistance offers to advance 1000 Dollars on the Credit of the Sale of the map in each of their Counties.[44]

Noticeably absent from the letter is any indication that the recipient, John Gray Blount, was a significant financial contributor, despite his obvious interest and need of an accurate map of the state. It must be remembered that the North Carolina General Assembly did not pay Price and Strother to perform any surveys or create a map with those surveys; the state government merely loaned a woefully inadequate sum to them to prosecute the work. Both men’s primary income was from Blount for surveying his vast land acquisitions throughout the state. In that capacity, John Gray Blount could arguably be considered, at least indirectly, the largest financial contributor to the eventual publication of the North Carolina map. Also, Blount may not have been in a benevolent mood in 1799 in regards to offering financial assistance for the map: The land bubble had burst and European war was seriously injuring the Blounts’ shipping trade with Europe and the West Indies.

Price and Strother collaborated on their coastal survey but, for most of the county surveys, they may have worked individually. Strother concentrated on the Piedmont and western counties while the eastern counties may have been Price’s responsibility. Referring again to Blount’s 11 May 1797 letter to Price:

I have this day rec’d a Letter [written 27 April] from J. Strother requesting me if I know where you are to inform you that he has compleated the Counties of Wake, Cumberland, Richmond, Anson, Montgomery, Rowan, Cabarrus, Mecklenburg, Lincoln, Rutherford Burk, Iredell, the SW part of Wilks [sic] part of Buncombe[.][45]

As of December 1796, approximately thirty county maps had been drawn.[46] The surveys and cartography for all counties were complete when Price wrote to Blount on 14 April 1799:

We may flatter ourselves the Map is complete the only thing now that seems to be default is to have it ingraved… [.] All that is wanted to be done now is to compile the whole again in order for the engraver[.][47]

Price’s statement of the map’s near completion may have been a few months premature. Based on the first state of the map’s western sheet, it is apparent that results of the North Carolina-Tennessee boundary survey performed in May and June 1799, compiled by John Strother and others, were also incorporated into the final manuscript.[48] [49] Unfortunately, extant documents don’t conclusively identify who compiled all the county maps into a single map. It almost certainly was either Jonathan Price or William Christmas, quite possibly the latter. William Christmas’s obituary reads, in part, “he was the principal person employed in drawing Price & Strother’s Map of N. Carolina.”[50] William Christmas was living in North Carolina in 1799, when the final manuscript may have been compiled, but he had moved to Tennessee by March 1800.[51] It is unknown whether the author of his obituary had firsthand knowledge that William Christmas had compiled the entire map, or if the author was giving excessive credit to the “Skillful artist” who had drawn the sample map submitted to the General Assembly as part of Nathaniel Christmas’s petition in 1792.

In March 1800, another letter was sent from Philadelphia to Blount with reference to the engraving of the map. In this instance, Richard Dobbs Spaight, North Carolina representative to Congress, wrote:

I have sent on to Strother all the information I could get respecting the engraving of the map of No Carolina, but have not recd. a line from him[.][52]

Presumably, Spaight was referring to terms for which the engraving could be done, though the possibility that he was referring to work already underway cannot be discounted.

With reasonable certainty it can be deduced that Strother became increasingly frustrated with the prolonged interval between completion of the manuscript and publication of the map. The following excerpts are from letters Strother wrote to John Gray Blount:

27 November 1800: …where is Price what is he doing, or done this summer past[?] do if you please advise me in that business for I am almost willing to lose sight of it —[53]

23 October 1801: Pray inform me what Price is [doing?] and, where he is[.][54]

Strother’s frustration is clearly evident in a postscript to a 5 September 1802 letter to John Gray Blount. Strother concluded: “Where is Price and what in gods name is he doing with the map[?]”[55]

Strother asked a very good question. Price was in Philadelphia tending to business related to the engraving of the map, but very little information survives about the particulars. On 28 February 1800, Price wrote to Governor Benjamin Williams: “I have arranged my business in such a manner as to be obliged to go to Philadelphia in May with our map.”[56] A 2 April 1801 letter from Governor Benjamin Williams reports that Price had gone to Philadelphia in September 1800 and was still there as of the date of the governor’s letter.[57] From a letter by Strother to John Gray Blount, we learn that Price had returned to North Carolina from Philadelphia before August 1801.[58]

There is virtually no mention of the map in the documentary record between 1800 and its eventual publication in 1807—the rare exceptions being the letters cited above and a few government records pertaining to the mapmakers’ debts to the North Carolina General Assembly. An example of the latter is a petition heard by the State Senate on 14 December 1802:

Mr. Blackledge presented the petition of John Strother, of the county of Buncombe, praying to be granted a longer indulgence for the repayment of the monies loaned to him and Jonathan Price some years ago, to enable them to complete a map of this State from actual survey. This petition was read, referred to the committee of propositions and grievances No. 2, and sent to the House of Commons.[59]

The “List of Delinquents” included annually in the North Carolina comptroller’s reports during this period showed the following debts: Price owed £400, Price & Strother jointly owed £500, and Price & Nathaniel Christmas jointly owed £290.[60]

As previously stated, Price and Strother intended for William Barker (engraver of their Cape Fear map) to engrave their North Carolina map. Unfortunately, Barker died of “a decay” at the age of 33 on 19 April 1803.[61] His death undoubtedly contributed to the delay in publication of the North Carolina map, but there are no surviving records that refer to a postponement or any efforts by Price and Strother to make alternative arrangements for the engraving and printing of the map. In fact, the next mention of the map is on 27 January 1808, when a copy of the completed, published map was presented to the United States Congress:

WEDNESDAY, January 27, 1808

On the motion of Mr. Blackledge, and seconded,

Resolved, That the librarian be directed to receive and take charge of the map of the state of North Carolina, presented to the House by Messrs. Jonathan Price and John Strother; and that the Speaker be requested to acknowledge the acceptance of the same.[62]

Publication of the Map

After the copy of the map was presented to Congress, another copy was donated to the American Philosophical Society at its meeting on 19 February 1808.[63] The North Carolina General Assembly also acknowledged receipt of a copy of the map during its 1808 session:

(Friday, December 23, 1808) Thomas Brownrigg, Esquire, the member of this house from the county of Chowan, presented the Senate with an elegant map of the State of North-Carolina, by Price and Strother, which was received by the Speaker with a suitable acknowledgement on the part of the house.[64]

The North Carolina Senate proposed a method to reciprocate for cartographic gifts that North Carolina had previously received from other states. However, the North Carolina House of Commons was not feeling generous in that regard:

(Friday, December 23, 1808) Received from the Senate, a resolution requesting the Governor to purchase as many of the maps of this State, edited by Price and Strother, as would enable him to send one to the Executives of each of the States. This resolution being read in this house was rejected.[65]

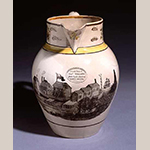

The question of whom would engrave and print the map after William Barker’s death in 1803 was answered at the bottom of the map’s title cartouche: The map was engraved by William Harrison (Jr.) and printed by his brother, Charles P. Harrison (Figure 10) of Philadelphia.[66] As declared in the title, the map is dedicated to North Carolina politician and judge David Stone (Figure 11) and Raleigh attorney and financier Peter Browne (Figure 12).[67] [68] The potential patrons that Price mentioned in his 1799 letter to John Gray Blount may have had a change of heart or contributed on a much smaller scale than Stone and Browne.[69] And Price seems to have considered acknowledgement of the two sponsors who were likely the largest direct contributors to its publication as more appropriate than a dedication to his employer, John Gray Blount.

Price and Strother’s monumental map was engraved on three copperplates and printed on three separate sheets of paper. The three sheets were usually joined as a wall map or broadside, or dissected and backed with linen and folded into a case map.[70] Obviously, each of the three copperplates could be revised independently of the other two, resulting in many potential combinations of the various states of each sheet to form a whole map—as a consequence, very few surviving copies of the map are identical. A review of the distinguishing features for the various known states of each sheet is presented in Appendix A. Examination of the currently known surviving copies of the Price-Strother map in public collections has revealed twelve different variants of the map and one incomplete variant (see Appendix B), including an 1826 revision published by Robert DeSilver that was recently discovered in the catalog of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (see Fig. 19).[71]

The earliest state of the map is undated, creating room for debate about the actual date of publication.[72] Fred Olds estimated a publication date of 1796 in his article and the North Carolina State Archives has assigned a publication date of 1798 to their copy; both are premature. Incorporation of Strother’s survey of the North Carolina and Tennessee boundary made the summer of 1799 makes it highly improbable that the map could have been engraved and printed prior to 1800. The fact that the map was not engraved by William Barker argues for a publication date after his death in 1803. Finally, the absence of any documentation of the map’s appearance prior to January 1808, strongly suggests that the first state of the map was printed no earlier than 1807.

Two bits of circumstantial evidence support a publication date of 1807 for the undated issue of the map. A catalog of books, maps, and charts in the United States Congressional Library, published prior to 11 April 1808, lists two maps pertaining to North Carolina:

North and South Carolina….By Mouzon, 1775

North Carolina….By Price and Strother, 1807[73]

This catalog entry suggests that, although Congress publicly acknowledged receipt of the map on 27 January 1808, the actual receipt of the map may have been recorded in 1807.

The second piece of evidence for an 1807 publication date is found in one of the earliest reviews of the map. The April 1808 issue of The Monthly Anthology, and Boston Review, begins: “The year 1807 has added another important map to our geography.” Like the Congressional Library catalog entry, this review implies a publication date of 1807.

Several other periodicals and newspapers in the United States and abroad published reviews of the Price-Strother map.[74] A review published in The Star (Raleigh) on 10 November 1808, is peculiar in that it relates to the undated first state of the map, although the revised 1808-dated map is documented as early as February 1808 through the American Philosophical Society’s copy. The Star’s review was subsequently reprinted, without credit, in the February 1809 issue of The Monthly Anthology, and Boston Review. The same periodical had earlier published the review, in April 1808, that suggested an 1807 publication date for the map.

Despite the generally favorable reviews and the fact that the map was, unequivocally, the most accurate of the state yet produced, all variants of the Price-Strother map, including the 1826 “improved” edition, contain a one-degree error in longitude. This is easily seen along the North Carolina and Virgina boundary, which runs almost seven degrees of longitude on the Price-Strother map, but slightly less than six degrees on essentially all other maps. This longitudinal error was noted and corrected by Henry Tanner in the compilation of his American Atlas, published in 1823.[75]

During a four-year period after the map’s initial publication (1808-1812), advertisements for the map appeared in several North Carolina newspapers (Figure 13), as well as in Philadelphia and New York newspapers.[76] The cost of the map at this time was $6.50 or $7. The price for subscribers, as advertised in 1797, was $4. The latest advertisement thus far located for the printed map is in John Melish’s 1822 catalog, which listed the Price-Strother map for $8.50.[77] No advertisements for the 1826 edition by Robert DeSilver have been found.

The advertisements and reviews may have benefitted sales to some extent, but the available records and scarcity of surviving copies suggest that the project was not a financial success—however, purchasers of the map included such notables as Aaron Burr, John Randolph, Christoph Ebeling, and Thomas Ruffin.[78]

Price and Strother After the Map

Upon completion of their Herculean task to publish their map, Price and Strother turned their attention to individual surveying projects and other interests. John Strother spent most of the period from 1800 to 1810 in the western part of North Carolina and in Tennessee. As during the previous decade, much of his efforts were focused on surveying land for John Gray Blount. During the War of 1812, Strother was appointed to the position of topographic engineer in General Andrew Jackson’s army. Strother was surveying the boundary between the Creek and Cherokee territories in Alabama when he died in August 1815.[79]

Throughout the first two decades of the nineteenth century, Jonathan Price continued to be active as a surveyor and cartographer. He participated in one of the earliest federally sponsored coastal surveys in 1806, the impressive results of which were, at least in part, responsible for establishment of the United States Coast Survey by Congress in 1807. In addition to surveys of the North Carolina’s rivers and coastal regions aimed at internal improvements in navigation, Price also completed several town surveys. Of his plans of Beaufort, Lenoxville, Washington, and New Bern, only that of New Bern was engraved and printed (Figure 14).[80]

In 1809, Jonathan Price’s debt of £1190 to the General Assembly was transferred to the University of North Carolina.[81] In view of “the scanty means and circumstances of the debtor,” the University Trustees ceased collection efforts in December 1817.[82] Jonathan Price died in New Bern on 23 May 1822. His estate, sold at auction in September of that year, included the following map-related items:

1 map colored…$3.50

1 map colored…$3.95 (Del’d)

1 map colored…$4.05

1 map colored…$4.00

5 maps unfinished…90¢/ea

20 maps unfinished…89¢/ea

# maps unfinished, the ballance…91¢/ea

1 Lot Maps at Raleigh (?)

1 Map State finished…$4.00

1 plate of the Plan of the Town…$10.00

1 plan Town…$1.05[83]

An amendment to the estate records was filed on 13 May 1825 by the administrator, Joseph Bell:

The admr of Jonathan Price amends the returns which he made to the Craven County Court as follows… he omitted in his account of sales 59 Maps of NoCarolina sold at 91/100 each [for a total of] $53.69.

Given the identical price per map, this amendment likely refers to “…maps unfinished, the balance” sold in New Bern, rather than to the “Lot of Maps at Raleigh.” Discounting the “Lot of Maps at Raleigh,” about which there is no available information, there were eighty-nine copies of the Price-Strother map sold at Price’s estate auction, the great majority purchased by Joseph Bell.

Bell paid ten dollars for the copperplate of Price’s Plan of New Bern and Dryborough (Fig. 14). He printed additional copies of the plan after having the plate updated to include images of the Presbyterian Church (completed in 1822) and the new Christ Church (completed in 1824).[84] Bell subsequently sold his ownership of the Washington Hotel in New Bern and moved to Alabama in the 1830s.[85] The fate of the maps he purchased, as well as the copperplate for the Plan of New Bern, is unknown. Perhaps those maps will one day turn up in a New Bern attic—and perhaps in the same trunk that Bell purchased from the estate of Jonathan Price.

Conclusion

The Price-Strother map of North Carolina is of monumental importance to the state’s cartographic history. The first map of the state to be made from an actual survey, it was published during a dramatic period of growth in North Carolina’s population and settlement of western lands. Along with the 1807 Bishop Madison map of Virginia, the Price-Strother map represents one of the first efforts to update the cartographic record of the American South after the War for Independence.

Jonathan Price and John Strother greatly advanced the geographical knowledge of North Carolina. Despite the one-degree longitudinal error, seen most obviously along the North Carolina and Virginia boundary, their map was easily the most accurate map of the state yet produced when it was published.

New information gleaned from government records and contemporaneous reviews—as well as close examination of extant copies—suggest that the Price-Strother map may have been first published in 1807, a year earlier than previously accepted. In the fifty years since the last scholarly assessment of the map, Mary Lindsey Thornton’s 1964 article, fourteen copies of the map have been identified in public collections representing twelve variants. And, most recently, a previously unrecorded 1826 revision published by Robert DeSilver was discovered in the catalog of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Although David Stone and Peter Browne received acknowledgment as the map’s patrons in the map’s title cartouche, the role of John Gray Blount in the development and eventual publication of Price and Strother’s map cannot be underestimated. The tremendous effort and dedication required of all of those men to see the project through to completion should continue to be “reflected on”—as Jonathan Price’s eulogist suggested in 1822—not underestimated or forgotten.

Jay Lester is an independent scholar living in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and a member of the William P. Cumming Map Society. He can be reached at [email protected].

Appendix A: Distinguishing Features for the Various States of the Price-Strother Map

|

Sheet |

1st State |

2nd State |

3rd State |

4th State |

5th State |

6th State |

|

Western |

W1 No date; DAVIE (in place of ASHE); BUNCOMB and WILKS (each lacking an “E”); engraver and printer imprints. |

W2 Corrected to show ASHE; no other changes. |

W3 Dated 1808; no other changes. |

W4 BUNCOMBE and WILKES (an “E” added to each); no other changes. |

W5 Printer’s imprint (C.P. Harrison) erased; no other changes. |

W6 1808 retained, but “Improved to 1826 By R.DeSilver” added to title; HAYWOOD COUNTY added (details therein derived from Tanner’s 1823 map); NC/SC boundary corrected; MORISTON changed to ASHVILLE. BUNCOMBE place name moved to accommodate Haywood County. |

|

Piedmont |

P1 IREDEL and ROAN |

P2 IREDELL and ROWAN |

P3* DAVIDSON COUNTY added; COLUMBUS COUNTY added. |

|||

|

Eastern |

E1 BEAUFORT COUNTY absent; EDGECOMB lacking an “E”. |

E2 BEAUFORT COUNTY added, but as BEAUFORD;Earl Granville’s Line added. |

E3 Corrected spelling of BEAUFORT COUNTY; no other changes. |

E4 EDGCOMBE (“E” added); no other changes. |

E5 GREENE COUNTY correctly named; BERTIE COUNTY place name now centered within county; BRUNSWICK COUNTY place name moved to accommodate Columbus County. |

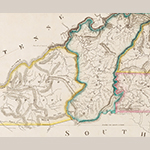

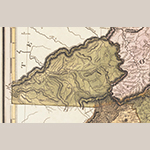

Western Sheet

The Western Sheet contains the map title. Six states of this sheet are known (hereinafter referred to as W1 through W6). The first two states of the Western Sheet (W1 and W2) are undated; all subsequent states have a printed date of 1808 in the title cartouche (see Fig. 10). Additionally, W1 contains a peculiar naming of the county in the northwest corner of the state: although Ashe County was erected in 1799, the county in this location is designated as Davie County, with an equally peculiar spelling of “D AD V I E”; i.e., the right “leg” of the letter “A” is conjoined with a wholly unnecessary “D” (Figure 15). This error was corrected to show Ashe County on W2 and subsequent states.

Perhaps Price and Strother were aware of an intent to honor William Richardson Davie, a former governor, Revolutionary War officer, and founder of the University of North Carolina. However, no records are available to indicate that Davie was ever considered as a potential name for what became Ashe County. The 1799 legislative records suggest that Davie lost out to Nathanael Greene as a replacement name for Glasgow County in the eastern part of the state.[86] In the end, however, William Davie wasn’t forgotten, he became the namesake of Davie County, carved out of northern Rowan County, in 1836.

Buncombe and Wilkes counties are spelled BUNCOMB and WILKS on W1 through W3, each receiving the absent “E” on W4 (Figures 16 and 17).

Although William Harrison’s imprint as engraver remains throughout all states, the printer’s imprint (C.P. Harrison) (Figure 18), present below and to the right of the title cartouche on W1 through W4, is erased on W5. The imprint of Robert DeSilver (“Improved to 1826 By R. DeSilver”) was added to W6. (Figures 19 and 20).

Haywood County (1808) was also added to W6, and the place names and topographic details within Haywood County were essentially copied from Henry Tanner’s 1823 map of North and South Carolina (Figures 21, 22, and 23). The boundary between North Carolina and South Carolina along the Blue Ridge, and from thence westward on the 35th parallel of north latitude, was corrected on W6.

Piedmont Sheet

The Piedmont Sheet exists in only three states (hereinafter referred to as P1 through P3).[87] The only difference in the first two of these states is the spelling of Iredell and Rowan counties (Figure 24); they were misspelled as “IREDEL” and “ROAN” on P1 and corrected on P2. The 1826 DeSilver issue (P3) shows two significant updates: Davidson (1822) and Columbus (1808) counties (see Fig. 19).

Eastern Sheet

The Eastern Sheet exists in five states (hereinafter referred to as E1 through E5). On E1, Beaufort County is absent (Figure 25). This is particularly surprising for two reasons: it had existed by that name since 1712 and its county seat of Washington was the home of Price & Strother’s employer, John Gray Blount. An exaggerated Hyde County erroneously includes the area of Beaufort County (and Blount’s 40,000-acre tract) on the first state of the Eastern Sheet. Beaufort County was added on E2, but with the erroneous spelling of “BEAUFORD.” Earl Granville’s Line was also added to E2. “BEAUFORD” was corrected to “BEAUFORT” on E3.

As with the Western Sheet, the letter “E” was rationed initially on the Eastern Sheet. States E1 through E3 show “EDGECOMB” for Edgecombe County; this was corrected on E4. Interestingly, Glasgow County retains that name on E1 through E4, despite having been renamed Greene County in 1799 (Figure 26).[88] The 1826 DeSilver issue (E5) correctly shows “GREENE COUNTY”; also, Bertie County’s place name has been repositioned to the center of the county (see Fig. 19).

Tyrrell, Pasquotank, and Lenoir counties are misspelled “TYRREL,” “PASOUOTANK,” and “LENEOIR,” respectively, on E1 through E5.

Appendix B: Variations and Locations of Extant Price-Strother Maps

|

Variant 1 (W1-P1-E1): |

North Carolina State Archives[89] |

|

Variant 2 (W2-P1-E3): |

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation[90] |

|

Variant 3 (W2-P1-E4): |

Harvard University[91] |

|

Variant 4 (W3-P1-E3): |

American Philosophical Society[92] |

|

Variant 5 (W4-P1-E3): |

North Carolina State Archives[93] |

|

Variant 6 (W4-P1-E4): |

|

|

Variant 7 (W4-P2-E2): |

|

|

Variant 8 (W4-P2-E3): |

|

|

Variant 9 (W4-P2-E4): |

|

|

Variant 10 (W5-P2-E2): |

United States National Archives[100] |

|

Variant 11 (W5-P2-E4): |

North Carolina Collection at UNC-Chapel Hill[101] |

|

Variant 12 (W6-P3-E5): |

Bibliothèque nationale de France[102] |

|

Incomplete |

Moravian Archives[103] |

|

Unknown |

Streeter Sale (1967); current location unknown[104] |

As previously mentioned, the Price-Strother map of North Carolina has been found in twelve extant sheet combinations. With the exception of Variant 1 and Variant 12, the numbers assigned to each are not meant to imply a chronological order of publication but merely a difference from other variants. Given the random combination of various states of the individual sheets, determining chronological order for each whole map is not possible. Of note, the Eastern Sheet was already in its fourth state when the American Philosophical Society acknowledged receipt of their copy of the map on 19 February 1808.

The Moravian Archives in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, has an incomplete copy that lacks the Western Sheet and has a large cut-out in the region of current Stokes and Forsyth counties from the Piedmont Sheet. The location of the Thomas W. Streeter copy, sold in 1967, is unknown. The unique copy held by the Bibliothèque nationale de France (see Fig. 19) is of particular interest, being published almost twenty years after the first state. Its imprint states that it was “Improved to 1826 By R.De Silver” (see Fig 20); although a more accurate imprint would have been “Improved in [author’s emphasis] 1826… .” This was undoubtedly an effort to make a quick profit from a perceived demand for a new map of North Carolina (such a project was already underway in North Carolina).

Philadelphia bookbinder and publisher Robert DeSilver likely saw the 25 May 1826 advertisement in a local newspaper for the sale of the copperplates of the Price-Strother map.[105] Although the original engraver’s imprint, William Harrison, is unchanged on the 1826 map, no records have been located to confirm who updated the copperplates for DeSilver in 1826. It very likely may have been the seller of the plates, James Porter, since William Harrison apparently had relocated to Georgetown, D.C., by 1825 and Porter was a well-known copperplate engraver and print publisher in Philadelphia.[106] Regardless of who did the engraving in 1826, the revision to the plates was quite cursory. Although three new counties are depicted (Haywood and Columbus [1808] and Davidson [1822]) and Greene County was correctly named, the 1826 map (see Fig. 19) fails to improve on any of the typographical errors of its predecessors, and most of the new towns established since 1808 (e.g., Greensboro) are not shown. Given that this map is currently known in only one surviving copy, the publisher likely did not achieve the intended profits.

Other historically documented copies of the Price-Strother map that are no longer extant include the copy donated by Price & Strother to the Library of Congress (destroyed when the British burned the Capitol in 1814); the library’s currently held copy was procured prior to 1827.[107] The Library Company of Philadelphia and the Charleston Library Society also previously held copies of the map.[108]

Appendix C: Price-Strother Map Timeline

|

1789 |

March |

Jonathan Price named surveyor of Pasquotank County. He conceives the idea of a new map of North Carolina and begins with surveys of the Edenton district. |

|

1790 |

December |

A bill for obtaining an accurate map of North Carolina was read once in the North Carolina State Senate and referred to the House, then tabled. |

|

1792 |

December |

Price and Nathaniel Christmas present separate petitions to the North Carolina General Assembly, each proposing to make a map of the state. |

|

1793 |

January |

North Carolina Governor Richard Dobbs Spaight authorizes an initial loan of £290 to Price and Christmas. |

|

1794 |

February |

Price and Christmas advertise in the North Carolina Journal (Halifax) soliciting subscribers to the map in an effort to generate cash to pay their county survey expenses. There is no further mention of Christmas in reference to the map other than records of his original shared debt of £290. |

|

1794 |

Price relinquishes his post as surveyor of Pasquotank County to accept employment from John Gray Blount. |

|

|

1795 |

February |

Price receives a loan of £300 from the General Assembly. |

|

1795 |

December |

Price unilaterally publishes a map and description of Ocracoke Inlet, much to the dismay of his new surveying partner and long-time Blount employee, John Strother. |

|

1796 |

March |

Price and Strother secure copyrights for a chart of the North Carolina coast and a map of the state. |

|

1796 |

December |

Price and Strother present thirty completed county surveys and receive a joint loan of £500 from the General Assembly. |

|

1798 |

Price and Strother publish an untitled chart of the entire coast of North Carolina, and also a map of Cape Fear River and its vicinity. |

|

|

1799 |

April |

Price announces in a letter to Blount that all of the county surveys had been completed and that a group of the state’s most respected citizens “being Desirious of giving us Assistance offers to advance 1000 Dollars on the Credit of the Sale of the map in each of their Counties.” |

|

1799 |

May and June |

Strother participates in the North Carolina and Tennessee boundary survey. The information from the survey is incorporated into the manuscript map. |

|

1800-02 |

Strother, in letters to Blount, laments the long delay in progress towards publication of the map. |

|

|

1800-01 |

The only documented evidence of Price traveling to Philadelphia to arrange publication of the map is revealed in a letter from Price to North Carolina Governor Benjamin Williams. Price reportedly left North Carolina no later than September 1800 and had returned by the summer of 1801. |

|

|

1803 |

April |

William Barker, engraver of Price and Strother’s Cape Fear map and the intended engraver of their North Carolina map, dies in Philadelphia. |

|

1804-07 |

No records have been located that mention anything about the progress (or lack thereof) towards the publication of the map. During this time, Price is involved with coastal surveys for the federal government and Strother is acting as surveyor and agent for Blount’s vast land holdings in Buncombe County, North Carolina. |

|

|

1808 |

January 27 |

Congress accepts the donation of a copy of Price and Strother’s map of North Carolina, the first documentation of the published map. |

|

1809 |

Price’s loan debt is transferred to the University of North Carolina. |

|

|

1815 |

August |

Strother dies in Alabama while surveying the Creek-Cherokee boundary. |

|

1817 |

Price’s plan of New Bern is published. |

|

|

1817 |

December |

The University of North Carolina ceases collection efforts from Price in view of “the scanty means and circumstances of the debtor.” |

|

1822 |

May |

Price dies in New Bern. |

|

1826 |

The copperplates for the Price-Strother map of North Carolina are purchased by Philadelphia publisher Robert DeSilver, who promptly publishes the map with very minimal updates. |

[1] Carolina Centinel (New Bern, NC), 1 June 1822. Jonathan Price’s eulogy was published anonymously, though some historians believe it to have been written by Francis L. Hawks (1798-1866), an Episcopal priest and North Carolina politician.

[2] Fred Olds, “North Carolina’s Collection of State Maps,” in The Orphans’ Friend and Masonic Journal, vol. L, no. 40 (26 February 1926): 1.

[3] Mary Lindsey Thornton, “The Price and Strother: First Actual Survey of the State of North Carolina,” North Carolina Historical Review, vol. 41, no. 4 (October 1964): 477-483. Online: https://archive.org/stream/northcarolinahis1964nort#page/n515/mode/2up (accessed 4 August 2014).

[4] Harry Roy Merrens, Colonial North Carolina in the Eighteenth Century (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1964), 53, 218. See also, Stella H. Sutherland, Population Distribution in Colonial America, (New York: AMS Press, 1966), 212.

[5] James Maury, “Letter of Rev. James Maury to Philip Ludwell, on the defence of the frontiers of Virginia, 1756,” contributed by Worthington Chauncey Ford in Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. XIX (July 1911), 293.

[6] Connecticut Courant (Hartford, CT), 30 November 1767 (transcribed with modern spelling).

[7] Although the 1770 map of North Carolina has traditionally been known as the “Collet” map, most of the map had been drawn by William Churton. Although Churton “had worked as a surveyor in the province for nearly 20 years, his name is not found on the map. Instead, authorship was claimed by John Collet. Churton died unexpectedly in December 1767 while surveying the southeast part of the province. His nearly completed manuscript was bequeathed to Governor Tryon, who assigned the task of completing the map to John Collet… However, since Collet was in North Carolina for no more than 12 months before returning to England with the manuscript map, it is very likely that his contributions to the overall cartography were minor.” From Jay Lester, “Did Mouzon, and perhaps ‘Others,’ copy the Churton-Collet map?” North Carolina Map Blog, 27 November 2012; online: http://blog.ncmaps.org/index.php/did-mouzon-or-perhaps-others-copy-the-churton-collet-map/ (accessed 27 May 2014).

[8] “Minutes of the North Carolina Senate and Minutes of the House of Commons, November 01, 1790 – December 15, 1790,” vol. 21, (Senate) 839, (House) 1013 and 1026. Online: (Senate) http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr21-0206 and (House): http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr21-0208 (accessed 27 May 2014). For the full text of the bill, see “General Assembly Petitions, Committee Reports, and Resolutions Pertaining to the 1808 Price-Strother map of North Carolina: 1790-1799,” in “Price-Strother map legal documents,” North Carolina Map Blog. Online: http://blog.ncmaps.org/index.php/price-strother-map-legal-documents/ (accessed 20 August 2014).

[9] William S. Powell, ed., Dictionary of North Carolina Biography (hereafter DNCB) (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979-1996), vol. 5 (P-S), 140. Jonathan Price biography online: http://ncpedia.org/biography/price-jonathan (accessed 27 May 2014).

[10] Powell, ed., DNCB, vol. 5 (P-S), 140. Jonathan Price biography online: http://ncpedia.org/biography/price-jonathan (accessed 27 May 2014).

[11] “Come under the care” is a phrase used to denote that an individual has requested to be considered for membership of a Quaker monthly meeting. For Price’s request and membership, see William Wade Hinshaw, ed., Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing, 1978 [reprint of 1936 original]), vol. 1 (North Carolina), 162.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Samuel Price was a member of Back Creek Monthly Meeting in Randolph County as late as 1811. Back Creek Monthly Meeting, Minutes (Men’s) 1792-1840, 269 (North Carolina Yearly Meeting Archive, Friends Historical Collection, Guilford College, Greensboro, NC).

[14] Hinshaw, ed., Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 162.

[15] Powell, ed., DNCB, vol. 5 (P-S), 140. Jonathan Price biography online: http://ncpedia.org/biography/price-jonathan (accessed 27 May 2014).

[16] Ibid.

[17] “North Carolina General Assembly Legislative Papers, 1784-1842,” 25 December 1792, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, #424-z. All available legislative documents pertaining to the Price-Strother map have been transcribed; see “General Assembly Petitions, Committee Reports, and Resolutions Pertaining to the 1808 Price-Strother map of North Carolina: 1790-1799,” in “Price-Strother map legal documents,” North Carolina Map Blog. Online: http://blog.ncmaps.org/index.php/price-strother-map-legal-documents/ (accessed 20 August 2014).

[18] Ibid.

[19] Powell, ed., DNCB, vol. 1 (A-C), 369. William Christmas biography online: http://ncpedia.org/biography/christmas-william (accessed 27 May 2014).

[20] Journal of the Senate, State of North Carolina, 26 December 1792 (Edenton, NC: Hodge & Wills, printers to the State, for the North Carolina General Assembly, Senate), 42.

[21] Journal of the Senate, State of North Carolina, 31 December 1792, 49; Journal of the House of Commons, State of North Carolina, 1 January 1793 (Edenton, NC: Hodge & Wills, printers to the State for the North Carolina General Assembly, House), 62. The author has been unable to confirm Thornton’s statement in her article that the loan was for £500 and a three-year term. North Carolina state records and University of North Carolina records consistently show Price & Christmas’s joint debt at £290. If Thornton did find evidence of approval for £500, perhaps the balance, or £210, was held in reserve for engraving and printing costs.

[22] Treasurer’s and Comptroller’s Papers, Executive Offices: Salaries and Contingent Expenses, Box 7, 3B.517. State Archives of North Carolina, Raleigh, NC.

[23] Petition of Jonathan Price, General Assembly Session Records, Dec. 1794–Feb. 1795, Box 2, MC.195.N534.1795uk. State Archives of North Carolina, Raleigh, NC.

[24] The North-Carolina Journal (Halifax, NC), 19 February 1794.

[25] Jonathan Price letter to the Secretary of the Board of Trustees, 21 July 1817, University of North Carolina Papers, 1757-1935, #40005, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. For John Strother, see Powell, ed., DNCB, vol. 5 (P-S), 467-69, John Strother biography online: http://ncpedia.org/biography/strother-john (accessed 27 May 2014).

[26] John Strother had two cousins of the same name, creating a challenge for subsequent genealogists and historians to positively identify John Strother the surveyor. Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Alice Barnwell Keith et al., eds., The John Gray Blount Papers, vols. I-IV (Raleigh, NC: Division of Archives and History, Department of Cultural Resources, 1952-1982), vol. I, 197.

[29] Powell, ed., DNCB, vol. 1 (A-C), 179.

[30] Elizabeth C. King, Comprehensive Architectural Survey of Beaufort County Phases II and III (Rural) Final Report (Greenville: North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office, Eastern Office), 26 (3 January 2011).

[31] Powell, ed., DNCB, vol. 1 (A-C), 179. Thomas Blount biography online: http://ncpedia.org/biography/blount-thomas (accessed 27 May 2014).

[32] Ocean-going vessels had a draft too deep for the shallow waters of Pamlico Sound. In a procedure referred to as lightering, the cargo was transferred to shallow-draft vessels, or flats, at Shell Castle for transport to inland ports such as New Bern and Washington. See Thomas J. Schoenbaum, Islands, Capes, and Sounds: The North Carolina Coast (Winston-Salem, NC: Blair Publishing, 1988), 157. See also Bland Simpson, The Inner Islands : A Carolinian’s Sound Country Chronicle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 79-84.

[33] William S. Powell, ed., Encyclopedia of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 1026; online: http://ncpedia.org/shell-castle (accessed 27 May 2014). See also see Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Success to the Tuley’ et.al via Liverpool,” MESDA Journal, vol. 2, no. 1 (May 1976): 1-26; online: https://archive.org/details/journalofearlyso21muse (accessed 27 May 2014).

[34] A description of Occacock [sic] Inlet… adorned with a map… by Jonathan Price (New Bern, NC: Francois Martin, 1795); State Archives of North Carolina, Raleigh, NC, MC.167.O21.1795p-p1.

[35] Keith et al., eds., Blount Papers, vol. II, 633

[36] Ibid, vol. II, 630

[37] Ibid, vol. III, 22

[38] Ibid, vol. III, 147.

[39] “Records of Copyrights, June 1796-1802 Circuit Court; and Admiralty Minutes U.S. District Court,” 4 March 1796, Record Group 21, National Archives and Records Administration, Federal Archives and Records Center, Atlanta, GA.

[40] The copyright claim was also published in the 23 March 1796 issue of the Aurora General Advertiser (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania).

[41] For another example, see the North Carolina Gazette (New Bern, NC), 2 April 1796, pp. 1 and 4. Online: http://cdm16062.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p15016coll1/id/14676/rec/1 and http://cdm16062.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p15016coll1/id/14676/rec/1 (accessed 27 May 2014).

[42] Jonathan Price and John Strother to Speaker of the House of Commons, 19 December 1798, Miscellaneous Petitions File, General Assembly Session Records Nov. – Dec. 1798, State Archives of North Carolina, Raleigh, NC.

[43] General Assembly Session Records Nov. – Dec. 1796, Box 3, Folder: (Nov.-Dec., 1796) Petitions (Miscellaneous), State Archives, Raleigh, NC.

[44] Keith et al., eds., Blount Papers, vol. III, 283-284.

[45] Ibid, vol. III, 147.

[46] General Assembly Session Records Nov. – Dec. 1796, Box 3, Folder: (Nov.-Dec., 1796) Petitions (Miscellaneous), State Archives, Raleigh, NC. Of the county surveys generated by Price and Strother, a map of Robeson County may be the sole extant example; online: http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ncmaps/id/3026 (accessed 27 May 2014).

[47] Keith et al., eds., Blount Papers, vol. III, 283-284.

[48] A “state” in cartographic terms refers to a particular printed version of a map, distinguished from other versions by modifications to its content.

[49] MC.185.1799mv, State Archives, Raleigh, NC; online: http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ncmaps/id/9655 (accessed 27 May 2014).

[50] Raleigh Register and North Carolina Gazette, 7 February 1812.

[51] Powell, ed., DNCB, vol. 1 (A-C), 369. William Christmas biography online: http://ncpedia.org/biography/christmas-william (accessed 27 May 2014).

[52] Keith et al., eds., Blount Papers, vol. III, 356.

[53] Ibid, vol. III, 454.

[54] Ibid, vol. III, 485.

[55] Ibid, vol. III, 537.

[56] Governors’ Letter Books 1764-1916, State Archives, Raleigh, NC; Letter Books, Office of the Governor, 1799-1802, Benjamin Williams, GLB.14, State Archives, Raleigh, NC.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Keith et al., eds., Blount Papers, vol. III, 483.

[59] Journal of the Senate of North Carolina… (Raleigh, NC: Printed by J. Gales, printer to the state, for the North Carolina General Assembly, Senate, 1803[?]), 43.

[60] Laws of North Carolina…, Comptroller’s Statement for the year 1802 (Raleigh, NC: Printed by J. Gales, printer to the state, 1803[?]); see alsoLaws of North Carolina…, Comptroller’s Statement for the year 1804, Appendix (Raleigh, NC: s.n., 1805[?]).

Although these titles are available in electronic format (access restricted to university faculty, students, and staff) through the University of North Carolina Libraries, the Comptroller’s statements for 1802 and 1804 are incomplete or not included in the electronic versions. The original complete records are available in the State Archives in Raleigh. The electronic edition of the 1803 Laws does include a “List of Delinquents”; Price et al are listed under the Edenton District (Pasquotank County).

[61] In Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia, PA), 27 April 1803.

[62] Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States… (Washington, DC: Printed by Gales & Seaton and reprinted by order of the House of Representatives, 1826), 146. Online: http://books.google.com/books?id=S54FAAAAQAAJ (accessed 27 May 2014).

[63] Early Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society… from the manuscript minutes of its meetings from 1744 to 1838 (Philadelphia, PA: Press of McCalla and Stavely, 1884), 404; online: http://books.google.com/books?id=4iQWAAAAYAAJ (accessed 27 May 2014). See also Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, held at Philadelphia… Volume VI (Philadelphia, PA: Published by C. and A. Conrad and Co., Jane Aitken, Printer, 1809), xxxv; online: http://books.google.com/books?id=DbkAAAAAYAAJ (accessed 27 May 2014).

[64] Journal of the Senate of North Carolina… (Raleigh, NC: Printed by J. Gales, printer to the state, for the North Carolina General Assembly, Senate, 1809[?]), 57 (1808 Session).

[65] Journal of the House of Commons of the State of North Carolina (Raleigh, NC: Printed by Gales & Seaton at the State Printing Office, 1809[?]), 57 (1808 Session).

[66] William Harrison (Jr.) and Charles P. Harrison were the grandsons of John Harrison, inventor of the first accurate marine chronometer for determining longitude; National Cyclopedia of American Biography (New York: James T. White, 1891 and 1907), vol. V, 208. Although William Harrison was an accomplished engraver of maps and miscellaneous views, he was also a prolific engraver of bank notes; Josephine French et al., Tooley’s Dictionary of Mapmakers, four volumes (Riverside, CT: Early World Press, 1999-2004), vol. E-J, 274-275; see also, William J. Harrison, comp., William Harrison, Sr. and sons, engravers: a check list of their work (South Yarmouth, MA: William J. Harrison, 1978).

[67] David Stone was born in Bertie County in 1770, graduated first in his class from the College of New Jersey (later named Princeton University) in 1788, and subsequently studied law under William Davie. Stone served the state government in numerous capacities, including in the North Carolina House of Commons, as a North Carolina Superior Court judge, in United States Congress (as both a representative and senator), and two consecutive terms as North Carolina governor; he was also a trustee of the University in Chapel Hill. Stone married Hannah Turner in 1793 and they eventually parented eleven children. David Stone had one of the largest libraries in the state. He resided at various times on Hope Plantation, located just outside of Windsor on the land where he was born in Bertie County, and at Restdale Plantation, situated on the Neuse River in his adopted Wake County. It was at the latter where Stone died in 1818 at the age of 48. Powell, ed., DNCB, vol. 5 (P-S), 457. David Stone biography online: http://ncpedia.org/biography/stone-david (accessed 27 May 2014).

[68] Peter Browne, born circa 1766, was a native of Knockadock in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. He arrived in America at an early age. Details of his early life and education are unknown. Browne practiced law in North Carolina, initially in Windsor, then Halifax, and finally in Raleigh, accumulating substantial wealth in the process. For a few years in the early 1800s he was owner of the previous home of Joel Lane, the oldest surviving house in Raleigh. Browne upset the locals by taking up the headstones of the Lane burial plot and planting a cabbage patch, likely as a money crop to cover taxes on the property. In addition to serving as one of the leading judges of Wake County, he also served as president of the State Bank of North Carolina in the latter years of his life. Browne was chairman of the inland navigation commission. During an extended trip to Britain beginning in 1818, acting as chairman of the inland navigation commission, he procured the services of two civil engineers for the state government: Hamilton Fulton and Robert H. B. Brazier (the latter would eventually become the compiler of the next great map of the North Carolina, the MacRae-Brazier map of 1833). Peter Browne died in Raleigh in 1834. Being a lifelong bachelor with no immediate family, his estate of more than a half million dollars was willed to a nephew in Scotland. Ibid, vol. 1 (A-C), 251. Peter Browne biography online: http://ncpedia.org/biography/browne-peter (accessed 27 May 2014).

[69] Keith et al., eds., Blount Papers, vol. III, 283-284.

[70] Given the protective covers, long-term survival of a case map should be much more likely than for a wall map. The approximately 6:1 ratio of surviving wall maps to surviving case maps suggests that very few copies were issued as case maps. This is speculation since there are no records indicating how many of the maps were issued in any format.

[71] Mary Lindsey Thornton and Fred Olds each wrote that there were two states of the Price-Strother map based on the two copies held by the North Carolina State Archives in Raleigh. Thornton, “The Price and Strother…,” 477-483; Olds, “North Carolina’s Collection of State Maps,” 1. For the 1826 DeSilver version, see Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, France; call no. FRBNF40745384. Online: http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb40745384d/PUBLIC (accessed 27 May 2014).

[72] State Archives, Raleigh, NC; MC.150.1798ps. Online: http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ncmaps/id/1210 (accessed 27 May 2014).

[73] Catalogue of the Books, Maps, and Charts, belonging to the Library established in the Capitol at the City of Washington, for the two Houses of Congress… (Washington, DC: A.&G. Way, printers, 1808), 34.

[74] See “Price-Strother map of NC: Reviews and Ads,” North Carolina Map Blog. Online: http://wp.me/p2GEda-jg (accessed 20 August 2014).

[75] Henry S. Tanner, A New American Atlas… (Philadelphia, PA: Henry S. Tanner, 1823), 15. Online: http://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/s/04k9i1 (accessed 27 May 2014).

[76] For other examples of advertisements of the map for sale in North Carolina, see 26 October 1809 The (Raleigh) Minerva and 4 January 1810 Raleigh Register and North-Carolina State Gazette.

[77] John Melish, Catalogue of Maps and Geographical Works, Published and For Sale by John Melish, For 1822 (Philadelphia, PA: John Melish, 1822), 24.

[78] See “Price-Strother map in contemporary letters,” North Carolina Map Blog. Online: http://wp.me/p2GEda-jy (accessed 20 August 2014).

[79] Powell, ed., DNCB, vol. 5 (P-S), 469.

[80] A Plan of the Town of Lenoxville, C,912c L57p, North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; online: http://dc.lib.unc.edu/u?/ncmaps,1005 (accessed 27 May 2014). The Plan of the Town of Washington, MC.195.W317.1794p, State Archives, Raleigh, NC; online http://dc.lib.unc.edu/u?/ncmaps,1068 (accessed 27 May 2014). A plan of the town of New Bern and Dryborough, see Fig. 14).

[81] Laws of North Carolina at a General Assembly… (Raleigh, NC: Printed by Gales & Seaton at the State Printing Office, 1809[?]), Chapter III, Paragraph II, p. 3). See also, “Price-Strother: a final letter,” North Carolina Map Blog. Online: http://blog.ncmaps.org/index.php/price-strother/ (accessed 20 August 2014).

[82] University of North Carolina Trustees Minutes, 16 December 1817, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. See also, “Price-Strother: a final letter,” North Carolina Map Blog, (online: http://blog.ncmaps.org/index.php/price-strother/ [accessed 20 August 2014]) for additional details pertaining to the trustees’ legal actions and Jonathan Price’s stirring letter to the trustees.

[83] Craven County Estate Records; Series: C.R. 028; Box: 508.116; Folder: Price, Jonathan; State Archives, Raleigh, NC.

[84] For an image of the first state of Price’s Plan of New Bern and Dryborough, see Fig. 14. For the second state, see Cm912c N53 1822, North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; online: http://dc.lib.unc.edu/u?/ncmaps,876 (accessed 27 May 2014). A lithographic facsimile of the second state was published circa 1858.

[85] In New Bern Sentinel, 29 August 1834.

[86] Personal communication from Anseley Wegner, Research Historian, North Carolina Office of Archives and History: “…some people in the 1799 assembly wanted to name a county Davie, but it wasn’t Ashe, it was the former Glasgow County (ultimately named Greene). The bill to rename Glasgow County has Greene marked out and replaced with Davie, which is then enclosed in boxes in two places. Greene is written off to the side in each case. The bill to divide Wilkes shows no such confusion.”

[87] For those unfamiliar with the topography of North Carolina, approximately the central or middle third of the state is commonly referred to as the Piedmont.

[88] James Glasgow, North Carolina Secretary of State from 1777 to 1798, resigned after details of the “Glasgow Land Fraud” were uncovered. John Gray Blount and Thomas Blount were also charged in that scandal. Although the reason that the county name Glasgow was retained on the map is not documented, it may have related to the close friendship Glasgow had with the employer of Price & Strother. James Glasgow biography online: http://ncpedia.org/biography/glasgow-james (accessed 27 May 2014).