In 2022, MESDA expanded its collecting and research focus to include Alabama as our eighth state. We celebrated this long-contemplated move with the exhibition Thrown Together: Pots and People of Early Alabama in 2023. Before the exhibition opened, we were alerted to a remarkable jug coming to auction at Crocker Farm, Inc. [1] It became MESDA’s first acquisition of an Alabama object and immediately went on view alongside other ceramic treasures from the state (Figure 1 and 2).[2]

The jug acquired by MESDA is attributed to the shop of Augustin Marchal (b. 1810).[3] Soft blue leaves curl up the sides of the vessel, culminating in dotted arcs that echo the overall shape of the object. It may perhaps be a representation of a cotton plant; the tulip-like shapes resemble the bolls that eventually mature into billowy puffs of fibers, and the dashed arches could arguably represent that later stage of development.[4]

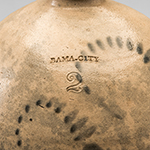

Augustin Marchal and his family immigrated to the eastern shore of the Mobile Bay from France and brought with them a distinctively European stoneware tradition. From the graceful ovoid silhouette to the high handle placement and use of salt glaze (as opposed to the alkaline glazes more prevalent in Alabama), it reflects wares they had known before their arrival.[5] Yet stamped across the shoulders is incontrovertible proof that they were on, and using, foreign soil: “BAMA-CITY” (Figure 3).[6] Naming mattered to the Marchals, or as they later became known, the Marshalls.[7]

New research has revealed that Augustin Marchal was born in Lavoye, a town in the department of Meuse in northeast France, on the border with modern-day Belgium. His father, Antoine Marchal, is listed in Augustin’s birth record as a pientre en fayance (painter on faience).[8] Finely decorated faience, or tin-glazed earthenware, was a specialty of potteries in Meuse (see Figure 4 for an example).[9]

By 1829, Augustin Marchal and his wife, Catherine Bouvier, moved to Pré-Saint-Gervais, a commune in the northeastern suburb of Paris. The birth record of his son Jean-Louis Marchal notes that Augustin was employed as a potier de terre, or earthenware potter.[10] This record was witnessed by two other earthenware potters.

The exact date of the Marchal family’s immigration to Alabama is still unknown. It must post-date the 1829 birth of Augustin’s son Jean-Louis and have occurred before the 1838 birth of his daughter, Mary, in Alabama.[11] Marchal first appears in the 1840 Baldwin County census in a household with his wife, three girls, and one boy.

Archaeologists Dr. Bonnie Gum and Dr. Greg Waselkov excavated the site of what is believed to be Augustin Marchal’s pottery just north of modern-day Fairhope, Alabama.[12] They discovered evidence that the pottery produced both lead-glazed earthenware and salt-glazed stoneware, although it is unclear if the two wares were manufactured simultaneously.[13] Among the wasters they recovered was a stilt with the impressed mark “AM,” presumably for Marchal.[14]

The story of Alabama pottery, as in so much of the craftsmanship of the American South, is one of migration and transformation. We catch our makers at different points in their creative journey: carrying out the traditions they knew, adapting to the approaches and markets they encountered, and pushing into new means of expression. Future research may clarify Marchal’s journey from earthenware to stoneware production, and where this jug fits in that evolution. For MESDA, the Marchal jug represents a new chapter in our journey of scholarship and collecting.

Lea C. Lane is curator of the MESDA Collection. She can be reached at [email protected]

[1] The jug was found at an antique mall in the northeastern United States and consigned to auction at Crocker Farm, Inc. Author correspondence with Luke Zipp, 27 February 2023.

[2] MESDA purchased the jug in honor of Joey Brackner, whose contributions to the study of Alabama ceramics, and MESDA’s entry into that world, is unparalleled.

[3] Only one other related jug from the Marchal shop has been discovered, which is now in a private Alabama collection. Joey Brackner, Alabama Folk Pottery (Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 2006), 79. Brackner’s attribution of the “Bama-City” vessels to Augustin Marchal is based on their similarity to later examples marked “Marshall & Co. Alabama City.” Almost all Marshall examples have cobalt decorations and tend to be more ovoid, in contrast with neighboring LaCoste family of potters, who stamped their wares “Ala-Coste” and typically did not use cobalt. Author correspondence with Joey Brackner, 12 February 2024.

[4] A curious aspect of the Marchal jugs, and ceramics by the shop of neighboring potter Francis LaCoste, is their creamy, opaque surface sometimes with scattered areas of a mottled blue. Both shops likely applied an opaque slip before the jug was fired. Additional research, including the use of XRF, may determine the identity of the opacifying material. Marchal’s familiarity with faience (tin-glazed earthenware) could explain his preference for decoration on a uniform white or cream ground. Author correspondence with Rob Hunter, 11 January 2024.

[5] Brackner, Alabama Folk Pottery, 79. Note: Alkaline glazing began by the 1820s in Alabama, brought by potters from Edgefield and Georgia. Brackner notes that “salt glazing was much more prevalent in Antebellum Alabama than many people believe. This may be because modern collectors overlook it in favor of…alkaline glazed.” The preference of salt glaze over alkaline mirrors settlement patterns, including migration from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Ohio into northern Alabama and from France into Mobile Bay.

[6] Alabama City was the original name of Fairhope in Baldwin County, Alabama.

[7] Naming is also not consistent. In French records, the surname name is spelled Marchal, which is the form used in this article. The potter’s first name, however, is shown as either Augustin or Auguste on these same documents. I have chosen to use Augustin, as this is how he appears on later Alabama records. In American records, the Marchal surname is spelled alternatively as Mareschal, Marshal, and Marshall.

[8] Birth record, Augustin Leonard Marchal, 22 mai 1810, Lavoye, Meuse, France, Archives départementales du Meuse; Bar le Duc, France; Etat Civil Registers, 1792–1902.

[9] Augustin Marchal’s birth record was witnessed by Jacques Boivin, who may have been part of the Boivin family that operated one of the tin-glazed earthenware potteries in Lavoye.

[10] Birth record, Jean-Louis Marchal, avril 1819, Pré-Saint-Gervais, Paris, France, Archives départementales de la Seine-Saint-Denis; Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, France; Etat Civil 1792–1912.

[11] 1860 census, Baldwin County, Alabama.

[12] For more information on the excavations of this site, please see Gums and Waselkov, Made of Alabama Clay: Historic Potteries on Mobile Bay, University of South Alabama, Center for Archaeological Studies, 2001. By the 1850s, Marchal and his family appears to have relocated to a pottery in nearby Montrose.

[13] Brackner, 79.

[14] This form of substantial wheel thrown stilts has been identified by Gums and Waselkov as “nearly unique to Eastern Shore [of Mobile Bay] pottery sites.” They compare favorably with kiln furniture found at an early 19th century faience kiln site at Dijon in east-central France, nearly due south of the Marchal’s hometown of Lavoye (Gums, 9). Stilts were used in the kiln loading technique known as rafters or “en chapelle.” Unfired objects were placed on slabs separated by kiln furniture like pegs, reels, or stilts. Marino Maggetti, “Technology and Provenancing of French faience,” Seminarios del la Sociedad Espanola de Mineralogia (2012) 9, 41–64, available online, https://www.semineral.es/websem/PdfServlet?mod=archivos&subMod=publicaciones&archivo=SeminSEMv9p41-64.pdf