The 144-page ledger book of cabinetmaker John C. Burgner (1797–1863) provides a remarkably complete picture of a furniture making shop during the first half of the nineteenth century in the rural American South. The ledger reveals the wide range of activities undertaken by Burgner’s shop over four decades of operation in East Tennessee and Western North Carolina. He recorded transactions with eighty individuals, both customers and employees, and the creation and repair of more than a thousand objects between 1818 and 1844. Burgner’s ledger is an invaluable document for the study of South’s early material culture. In many ways it is of even greater significance than even the oft-cited account book of the eighteenth-century South Carolina cabinetmaker Thomas Elfe because of its level of detail and chronological scope.[1]

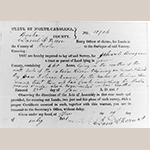

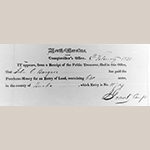

John C. Burgner used his ledger book for two purposes: as an account book and as a waste book. Beginning in 1818, working from the front of the ledger toward the back, Burgner kept an account book where he noted credit extended to his neighbors, workmen, and apprentices as well as their repayment in cash or other goods (Figure 1). He also maintained a waste book, starting from the back of the ledger and working towards the front, recording a complete list of the diverse work performed in his shop (Figure 2). In one year alone workmen in the shop could be found preparing gallows for the county, building a secretary bookcase, making a dulcimer, and repairing a sideboard.[2]

Although there are gaps in its chronology, the ledger documents the operation of Burgner’s shop in three different locations: the Horse Creek area of the Nolichucky River Valley of Greene and Washington counties, Tennessee, between 1818 and 1825; in Morganton, Burke County, North Carolina, between 1825 and 1836; and in Waynesville, Haywood County, North Carolina, between 1842 and 1844. Currently, the ledger book resides in the collection of the Haywood County Historical & Genealogical Society in Waynesville; a photocopy is held by the Gray Library at Old Salem Museums & Gardens in Winston-Salem.[3]

The goal of this article is to contextualize Burgner’s ledger book and to present it as a resource for those studying the various aspects of craftsmanship and community in the early southern Backcountry. The article is presented in three parts: The first is a chronological summary of John C. Burgner’s life and shop production based on a close examination of the ledger book, family histories, and other historical resources. The second is an analysis of the furniture forms and work performed in Burgner’s shop as recorded in the ledger’s waste book. Thirdly, the ledger in its entirety can be viewed and downloaded as a PDF document by clicking here.

The dual purpose and evolving organization of Burgner’s ledger allow for many different modes of analysis, providing researchers the opportunity to utilize it for their own purposes. Economic historians can find great value in the ledger book’s detailed records of one cabinetmaker’s financial relationships with his customers and workers over time. The ledger’s detailed listing of daily, weekly, monthly, and annual production make it an important resource for understanding seasonality and change over time in the antebellum rural South. Researches interested in labor history and craft practice can use the ledger to identify nineteenth-century rural cabinetshop practices by studying the forms and amount of furniture produced by individual journeymen and apprentices. As such, the breadth, depth, and adaptability of John C. Burgner’s ledger book establish it as one of the most important surviving documents for the study of cabinetmaking in the early American South.

John C. Burgner, Cabinetmaker

John Calvin Burgner was born in Woodstock, Virginia on 30 October 1797. He was the first of nine children born to Peter Burgner (1773–1824) and Elizabeth Cline Burgner (1776–1852).[4] At least four of John C. Burgner’s brothers are also documented as having been woodworkers: Henry Burgner (1806–1879) and Jacob Forney Burgner (1808–1865) appear in the ledger book working in their brother’s shop; census records and surviving furniture marked or owned by Christian Burgner (1811–1886) and Daniel Forney Burgner (1817–1902) demonstrate their participation in the cabinetmaking trade as well.[5] Cumulatively, the members of this generation of the Burgner family made furniture in East Tennessee for nine decades.

Burgner’s ancestors, Peter Burgner (1694–1768) and his two adult sons Christian (1717–1754) and Peter (1719–1784), arrived at the port of Philadelphia in 1742 aboard the brigantine Mary.[6] They hailed from Grindelwald, Switzerland, where the elder Peter was a merchant tailor.[7] According to a nineteenth-century family history, the “Burgner brothers (Christian and the younger Peter) were carpenters by trade and worked among farmers in Lancaster and adjoining counties building houses and bank barns, after Swiss models… .”[8] Christian Burgner married Anna Barbara Bowman (1716–1790) in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 1747.[9]

Christian and Anna Barbara Bowman Burgner’s second son, Christian Peter Burgner (b.1750), served as a private in the Lancaster County Militia during the American Revolution. Following the war he felt the pull of the Shenandoah Valley with its promise of cheaper land.[10] The family settled first in Funkstown, Maryland and then in Woodstock, Virginia.[11] In 1796 Christian Peter Burgner’s oldest son, Peter (1773–1824) married Elizabeth Cline (1776–1852).[12] The couple had five children in Woodstock: John Calvin (the cabinetmaker whose ledger book is the focus of this article), Peter (1800–1828), Elizabeth (1803–1854), Henry (1806–1879) and Jacob Forney Burgner (1808–1865).[13]

In 1810, the thirty-seven-year-old Peter Burgner decided to move his family further west, acquiring two hundred acres of a land grant on the south side of the Nolichucky River in Washington County, Tennessee.[14] Two years later, the family crossed the county line into neighboring Greene County, Tennessee.[15] There Peter Burgner purchased one hundred acres on the Little Limestone River in Washington County from Ira Green for $400.[16] Like many in the Nolichucky River Valley, Peter Burgner owned property on both sides of the Greene-Washington county line (Figures 3 and 4).

The Burgner family’s neighbors in the Nolichucky River Valley included the Earnests, who were among the region’s earliest settlers. The Earnest patriarch, Henry Earnest (1732–1809), built a fort-style house overlooking the Nolichucky River in the early 1780s (Figure 5).[17] His son, also named Henry (1772–1851), is the fourth name listed in John C. Burgner’s account book. Henry Earnest Sr. and his children played an important role in the establishment of Methodism in Tennessee. They founded the first Methodist Society in the state, originally called the Western Conference and later renamed the Holston Conference.[18] The family donated the land for Ebeneezer Methodist Church—where most of the Earnests were buried—and the annual meeting of the Holston Conference was held in the Nolichucky River Valley six times between 1795 and 1821. In 1806, Henry Earnest’s son, Felix, was ordained a deacon by Bishop Francis Asbury, who was one of the founders of the Methodist Episcopal Church in America.[19]

Religion may have played a significant role in John C. Burgner’s parents’ choice of the Nolichucky River Valley as their new home. Although the Burgners had been associated with the Lutheran Church in Pennsylvania, it is entirely possible that the family embraced evangelicalism and Methodism upon their arrival in the Shenandoah Valley in the 1780s.[20] According to family tradition, John C. Burgner’s grandfather, Christian Peter Burgner, was a circuit riding Methodist minister.[21] Bishop Asbury visited Shenandoah County at least eight times during his ministry. He preached in Woodstock in 1790 and again in 1801 and visited Tennessee’s Nolichucky River Valley six times between 1796 and 1815.[22] Interestingly, John C. Burgner’s last known piece of woodwork was a pulpit made for the Pleasant Hill Methodist Church in 1858.[23]

Peter Burgner noted in his 1824 will that his son John had “voluntarily and of (his) own free will (taken his) liberty from the age of fifteen years.”[24] This passage suggests that John C. Burgner’s apprenticeship began around 1812, after the family’s move to the Nolichucky River Valley. Although his ancestors had been builders and woodworkers, there is no indication that his father ever practiced the trade. Instead, John C. Burgner may have apprenticed under John Mathews, whose Greene County cabinetshop in 1820 produced two desks, five bureaus, five cupboards, and twelve tables.[25] Mathews was born in Maryland and probably trained there.[26] Methodism may have brought the Burgner and Mathews families together. The 1850 Federal Census for Greene County, Tennessee, listed Mathews as a cabinetmaker living adjacent to two Methodist ministers. And John Mathews married Amy Earnest, the daughter of the Reverend Felix Earnest, Burgner’s neighbor and client.[27]

John C. Burgner and his brothers built furniture in the Nolichucky River Valley for nearly nine-decades. This fact makes Burgner-attributed furniture plentiful in East Tennessee; But the Burgner brothers were part of a larger East Tennessee craftsman community. On close examination some objects with long-held Burgner attributions may in fact be the work of other local craftsmen working within the same regional style vocabulary. This article focuses exclusively on objects that are signed, documented, or have strong Burgner family histories coupled with construction characteristics that are consistent with the signed and documented pieces. The goal of this article is not to produce a catalog raissoné of Burgner Family furniture but instead to examine the cabinetmaking career of John C. Burgner through an analysis of his ledger book.

The earliest surviving example of John C. Burgner furniture is a sideboard made in 1817 or 1818 for William Blackburn (Figures 6 and 7). Burgner charged Blackburn $162.50 for the sideboard. Nearly forty years later Burgner signed it when the sideboard returned to his shop for repairs and modification. This particular sideboard is not listed in Burgner’s ledger book, which suggests that either Burgner was not yet keeping his own shop or that Blackburn had paid cash; however, Blackburn is listed on the very first page of the account book where he was charged $2.50 for “one knife box.” Blackburn was married to Sarah Broyles (b.1804), whose father Simeon Broyles (b.1779) is also listed in the first pages of Burgner’s accounts, acquiring a bureau for $17 and a chimneypiece for $7 in August 1818.[28]

When William Blackburn and his family moved from the Nolichucky River Valley to Mississippi and then to Texas, he left his sideboard behind with the Broyles family. It eventually found a home with Adam Alexander Broyles (1813–1900) who returned the sideboard to Burgner’s shop in 1856 for repair and refurbishment, including the addition of the glove drawers and a mirror. Made in 1817 or 1818 and refurbished in 1856, the Blackburn-Broyles sideboard is simultaneously John C. Burgner’s first and last known piece of signed furniture.

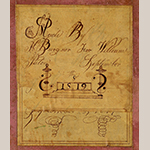

One of the most intriguing elements of the Blackburn-Broyles sideboard is its musical drawer (Figure 8). Part alarm system and part clever conceit, upon opening the top center drawer a quill is strummed across a stringed instrument concealed inside. Burgner used the same technique on a secretary desk he made for William Patton in 1819 (Figures 9 and 10). On opening the Patton desk’s secretary drawer a quill strums the 26-stringed instrument—essentially a zither—inset into the top of the case (Figure 11). To hear the zither being played by opening the drawer of the secretary desk, click the play button below.[29] Burgner celebrated his desk’s musicality on the elaborate paper label affixed to the inside of the Patton desk’s prospect door (Figure 12). Significantly, the word “Made” on the label incorporates a representation of a hand and the classical base inscribed with the date “1819” is flanked by two highly stylized G clefs. Burgner evidently put a great deal of thought into this label and took some pride in its appearance as an earlier, plainer, draft of the label is visible below the present one.

Audio Recording of the Zither in the John C. Burgner Secretary Desk

(Courtesy of the Tennessee State Museum)

The Blackburn-Broyles sideboard and the Patton desk share aesthetic characteristics that define much of the large body of surviving furniture associated with John C. Burgner and his brothers. Like many other examples made by Burgner family members, the sideboard and desk make careful and creative use of highly figured lumber from the abundant walnut, cherry, and maple trees that grow in the mountains of East Tennessee. Sometimes used as solid boards, and sometimes sawn into thick veneers, Burgner and his brothers used this local lumber to create dramatic surfaces for their furniture.

Burgner and his brothers made creative and decorative use of natural wood formations such as burls and knots. On the Patton desk he sawed a single burl into matching veneer panels for the outside of the secretary drawer and the prospect door inside. A similar technique featuring wood knots was used on a press made by one of the Burgner brothers, acquired by the late Richard Harrison Doughty, a prominent Greene County collector and antiquarian, and now in the collection of the Dickson Williams Mansion in Greeneville (Figures 13 and 14). This technique was also used on another chest of drawers with a history in Christian Burgner’s household (Figure 15).

Another sideboard (Figure 16), made by Christian Burgner for his house on Horse Creek (Figure 17) and now in the MESDA collection, provides an excellent example of how rural cabinetmakers like the Burgner brothers might approach a plentiful supply of figured wood. An urban cabinetmaker would have been incentivized to slice a heavily figured board into as many veneers as possible due to the expense of acquiring such costly materials. In contrast, most likely due to Christian Burgner’s easy and inexpensive access to ample amounts of figured lumber in the forests of East Tennessee, the sideboard in Fig. 16 was constructed using both solid curly walnut boards and veneers of curly walnut. The flat section of the turned post on the left is veneered with a flitch sawn from the post on the right. The top right and left drawers are veneered with flitches sliced from the drawers below. The middle bottom drawer is veneered with a flitch from the top. Although now much obscured by an old and decaying finish, Christian Burgner’s technique achieved a book-matched effect with just half of the veneer work; something that was only possible because he had plentiful access to curly walnut.

In March 1820 John C. Burgner hired his first documented journeyman, John Kitchen Dawson (1797–1888). Dawson was born in Caswell County, North Carolina and, according to a published biographical note, at sixteen he left home to briefly work in the lead mines of Wythe County, Virginia. In 1814 he returned to North Carolina and then in 1818 he left North Carolina for Greene County, Tennessee, where “after a short time spent at school he apprenticed himself to the cabinet making business.”[30] The addition of another hand precipitated Burgner to begin his waste book of all work performed, noting that the work on an object was done by either “Burgner” or “Dawson.” He later simplified the system by noting that either “B” or “D” had done the work.[31] Like a number of Burgner’s journeymen, Dawson would eventually move west. In September 1822 he married Sarah Bitner (b.1802) in Sevier County, Tennessee. In 1826 he became a licensed preacher in the Methodist Episcopal Church. And three years later the couple moved first to Indiana and then even further west to Iowa.[32]

In June of 1822 the initials “HB” appear in the account book for the first time, probably referring to John’s younger brother Henry Burgner, whose apprenticeship, according to their father’s will, began the previous year when he turned fifteen years old.[33] After Dawson’s departure in August 1822, notations in the waste book using the workers’ initials stopped, perhaps suggesting that Henry Burgner was still serving his apprenticeship and that the brothers were alone in the shop—with only a master and apprentice at work, there was no need to account separately for each brother’s output.

The death of Peter Burgner on 9 June 1824 brought his eldest son new responsibilities and opportunities. Appointed executor, John C. Burgner set about settling the estate’s debts—including a $44.97 doctor’s bill—and fulfilling his father’s final wishes.[34] After providing for his wife, Peter Burgner left the proceeds from the sale of his moveable property to his daughters. He left land to each of his sons except for Henry and John C. Burgner. To them he left $100 each to be paid “in a good horse,” presumably because they had chosen to take up a trade rather than farming.[35]

Six months after Peter Burgner’s death, on 15 and 16 December 1824, John C. Burgner recorded that his shop completed work on a bureau, “one top for (a) Chiny Press”, a pair of bedsteads, and “the finishing of one carriage.”[36] Shortly thereafter Burgner used his “good horse” to leave the Nolichucky River Valley for Morganton, North Carolina, where he established a new cabinetshop by February 1825.[37]

Family connections and economic opportunities lured Burgner to Morganton, the county seat of Burke County (Figures 18 and 19). Burke and neighboring Lincoln County were home to his Forney cousins. Burgner’s great-great aunt, Maria Burgner (1721–1810), had married Jacob Forney (1721–1806) and the couple was among the earliest settlers in the Catawba River Valley, arriving via the Great Wagon Road about 1754.[38] A continued closeness of the family’s two branches is suggested by the fact that two of John C. Burgner’s siblings carried “Forney” as their middle name. In addition, two of Jacob and Maria Forney’s children appear in Burgner’s account book: Peter Forney (1754–1834) and Jacob Forney Jr. (1764–1840).[39]

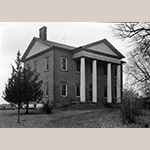

Peter Forney fought with distinction in the American Revolution, was active in the region’s iron industry, served in the United States House of Representatives, and built an impressive house, which he named Ingleside (Figure 20).[40] Although he could easily have patronized craftsmen in Lincoln County, in 1827 he purchased a number of items from his cousin John C. Burgner’s shop in Burke County, including a $75 commode, paying for his purchases in cash, iron, and metal casting.[41]

Jacob Forney Jr. began work on a new house outside of Morganton shortly after Burgner arrived in Burke County (Figure 21). A fragment of Forney’s journal records that “On the 4 day of May 1825 we began (to) build our house.” The following entry in the journal noted, “we Moved into our New house on tuesday the fift [sic] of December in the year of our Lord One thousand Eight hundred and twenty Six”.[42] Some of the four mantelpieces recorded in Burgner’s waste book during this time could have been made for Jacob Forney’s house. Likewise, the “one cutting box” recorded on 11 January 1826 might have been related to Forney’s house.[43] Of special interest is the tabletop secretary bookcase that descended in the Jacob Forney family stamped with John C. Burgner’s tool (Figures 22, 23, and 24).[44]

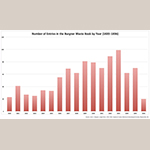

Burgner’s connection with the Forney family enabled him to quickly build a clientele among Burke County’s elite, including members of the Tate, McDowell, and Erwin families.[45] Due to these connections, Burgner’s shop prospered in Morganton. In 1823, the last full year he worked in the Nolichucky River Valley, Burgner recorded twenty-five entries in his waste book (Figure 25). In 1826, just a year after he had moved to Morganton, Burgner completed more than twice as much work. To enable this increased production, his brother Henry Burgner joined the shop in January 1824 and later that year John P. Furr was hired as a journeyman.[46] Another brother, Jacob Forney Burgner, began working in his brother’s Morganton shop by February 1827 when he was credited with making “one Bureau & Bookcase” valued at $30.[47]

With the success of his Morganton cabinetmaking operation, Burgner started a family. In March 1829 he married Eliza B. Cobb, whom he described as “the most beautiful and accomplished women in Abbeville, South Carolina” (Figure 26).[48] The couple welcomed their first child, Jacob Cobb Burgner, in 1831, an event commemorated in Burgner’s waste book with an entry for “one crib for J.C.B. by him.”[49] The couple would have six more children together: James (b.1830), Elizabeth (b.1832), John (b.1834), Walter (b.1835), Mary (b.1840), and Elbert (b.1842).[50] Burgner’s waste book records objects made for his family on occasion, including “one fancy chair… for his wife,” recorded on 20 January 1831.[51]

Burgner also became involved in Morganton politics, qualifying as a justice of the peace in 1831.[52] His role in the county court led to his involvement in the sensationalized murder trial of Frances Stewart Silver (c.1815–1833), better known in popular culture as the heroine Frankie Silver. On 22 December 1831, Frankie’s husband, Charlie Silver, disappeared and Frankie was implicated in his death. Authorities issued a warrant for Frankie Silver’s arrest on 9 January 1832. Four days later her father filed a writ of habeas corpus before county magistrates, one of whom was the cabinetmaker and justice of the peace John C. Burgner.

At her trial in March 1831, Frankie Silver was found guilty and sentenced to hang.[53] Her case was appealed, and more than a year later, on 7 June 1833, John C. Burgner was paid $2.50 for “work done on F Silver’s gallows.”[54] Frankie Silver escaped from prison shortly after Burgner and his crew had prepared her gallows. When she was recaptured a month later, Burgner was paid an additional $2.00 for work on the gallows.[55] Frankie Silver was hanged the next day, on 12 July 1833, only the second woman to be executed in North Carolina.[56]

Frankie Silver’s death inspired a folk ballad that purported to capture her confession of the crime.[57] The ballad was first printed in the Lenoir, North Carolina, newspaper on 24 March 1885 and its publication drew a response from Henry Spainhower (1819–1901), a Lenoir native who had by then relocated to Kentucky. Spainhower wrote to the newspaper that the ballad maliciously misrepresented Frankie Silver’s crime because everyone knew she had acted in self-defense:

Some person not acquainted with the facts must have done it [written the ballad]. I consider it wrong to brand the dead with greater crimes than we believe they were guilty of.[58]

Spainhower was in an excellent position to know about such events because Frankie Silver “was hanged right in fair view of the place where I was at work.”[59] He had a “fair view” of her gallows because Spainhower had been a journeyman in the cabinetmaking shop of John C. Burgner from 1831 until 1833. Born in Burke County, Spainhower married in 1839 and moved first to Rockbridge County, Virginia, and then to Garrard County, Kentucky (Figure 27), where his obituary recorded he was “a cabinet maker and undertaker for over 60 years” (Figure 28).[60]

Burgner’s shop was successful enough to employ at least five hands by 1831: Jacob F. Burgner, Michael Setherwood, John McTaggart, Henry Spainhower, and Samuel Wycough, Although Burgner had employed journeymen and apprentices since beginning his waste book eleven years earlier, a runaway apprentice in March 1831 spurred another change in his bookkeeping.[61] Before then, Burgner’s shop output was recorded sequentially with the initials of each journeyman. After March 1831 each craftsman employed by Burgner received a page of his own. In addition to Henry Spainhower and Jacob Forney Burgner, at various times between 1831 and 1836 the shop would also employ, A.H. Campbell, Samuel Capeheart, David Dellinger, Henry Long, R.C. Spears, and James Taylor.[62]

Many of Burgner’s journeymen would ultimately be caught up in the great wave of mid-nineteenth-century westward migration. Born in Virginia, Rice C. Spears (1812–1871) worked in the Burgner shop between 1834 and 1835, making sideboards, bureaus, secretaries, and other forms.[63] By 1850 he had moved to Monroe County, Tennessee, southwest of Knoxville.[64] Samuel Wycough (1809–1880) was born in Salisbury, North Carolina, where he apprenticed as a cabinetmaker. In late 1831 he began work as a journeyman in Burgner’s shop in Morganton. He continued there for two years before, in the words of a later biographer, “coming from his native state to Arkansas… where ere long he became a citizen of prominence and influence.”[65]

While his journeymen moved to new towns in the West, John C. Burgner put down roots in Burke County. In June 1831 he acquired a warrant for 640 acres that he patented and purchased in February 1833 (Figures 29, 30, and 31).[66] The busiest year recorded in his shop was 1833, with ninety-nine entries in the waste book. Perhaps an indication that Burgner was shifting his attention to agricultural pursuits, shop output fell in 1834 by almost a third. Productivity recovered slightly in 1835 only to plummet again in 1836 to the lowest level recorded in either the Nolichucky River Valley or Burke County.

The Panic of 1837 was probably the final straw for John C. Burgner’s cabinetmaking shop in Burke County, North Carolina. By July, Burgner had returned to Tennessee where he recorded in his ledger book that he had plowed and cleared ground for his brother, Christian Burgner.[67] Three years later, the 1840 Federal Census recorded that he was living with his wife Eliza and five children adjacent to his brother Christian Burgner on the banks of Horse Creek on the Nolichucky River. The 1850 Federal Census lists Christian Burgner as a cabinetmaker living with his wife Malinda in Greene County, Tennessee. It is not known under whom Christian Burgner apprenticed, but he did not turn fifteen until 1826, the year after John C. Burgner had established himself in Morganton. With his eldest brother gone, perhaps Christian turned to one of his other brothers, Jacob or Henry, to learn the trade of cabinetmaking.

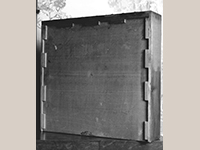

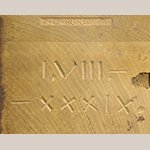

A punched-tin-decorated safe (Figure 32) with a history in Washington County, Tennessee, stamped “CB” on its lower back post has been attributed to Christian Burgner.[68] Although his name does not appear as a craftsman in John C. Burgner’s ledger book, the similarity of construction techniques between the brothers’ work suggests at least some direct or indirect shared training. For instance, when constructing drawers, both brothers used beveled bottom boards with segmented glue blocks to secure them into place (Figures 33 and 34). This detail is not seen in all Greene County and Washington County cabinetwork, but it is consistently seen on examples closely connected to members of the Burgner family.

John C. Burgner continued to make furniture after he left Morganton, though he did not record his activities in the ledger book—possibly due to a paucity of commissions or the fact that he was working alone in his shop. That Burgner was still making furniture is evidenced by a sideboard which belonged to Ozey Reed Broyles (1819–1907) and his wife, Sarah Wilhoit Broyles, that is struck with John C. Burgner’s tool stamp and dated 1839 (Figures 35, 36, and 37).[69] In addition to furniture making, Burgner turned his attention to agricultural pursuits in the early 1840s, particularly the cultivation of silk, which according to one source was destined to “shortly become one of the staple productions of East Tennessee.” The few entries he made in his ledger book during the time he lived on Horse Creek record the sale of morus multicaulis buds—a variety of Mulberry tree—for the cultivation of silk worms (Figure 38).[70]

In 1842 John C. Burgner and his family left the Nolichucky River Valley for Waynesville in Haywood County, North Carolina (Fig. 19). He once again began to note furniture production in his waste book, recording fifty-three entries between 1842 and 1844 and taking on at least three journeymen or apprentices.[71] In Waynesville, John and Eliza became acquainted with James R. Love (1798–1863) and his wife Maria (1805–1847). Love was one of the wealthiest men in Haywood County. In May 1843 Burgner repaired a bureau and built “one French Bedstead” for him.[72] Unfortunately for Burgner, Love also had a reputation as being “the greatest debaucher in the county,” and it was recounted that James Love and Eliza Burgner “met at a neighbors house from which a thunderous report issued.”

Although Burgner tried repeatedly to get his wife to end the relationship, she refused, continuing her affair with Love in their “own house” during which times she would “turn all of the… children out of doors… refusing any and all of [the] children admittance for upwards of half a day… .” Burgner tried to persuade Eliza to leave Waynesville, but Love induced Eliza’s brother, David Cobb, to buy a plantation from him for his sister, after which time she told her husband that “she never would go back [to Tennessee].” She informed Burgner that “she had a house of her own and she would show him… that she could make a living.” Eliza Burgner then proceeded to “sell off at great sacrifice [his] property”, told him to “take the children away,” and informed him in a letter that “we will be two people hereafter and the sooner the better.”[73]

The last entry in John C. Burgner’s ledger is from 1844 and records a $4.00 table made for a member of the Rineheart family.[74] In 1847 John C. Burgner and five of the his six children returned to the Nolichucky River Valley to take care of his elderly mother. In October 1849 he filed for a divorce from Eliza, which was granted in March 1850.[75] The 1850 Federal Census for Washington County, Tennessee recorded John C. Burgner living in a household with his 73-year-old mother and five children. There is no record for Eliza Burgner in the 1850 census or for their son Walter, who would have been about 15 years old at the time. James R. Love is shown in 1850 living in Haywood County, North Carolina with his seven children and an estate valued at $50,000. His wife, Maria, had died three years earlier.[76]

Caring for his ailing mother was a significant enough role that John C. Burgner’s occupation in the 1850 Federal Census was listed as “Physician,” although he continued to do some woodworking throughout the 1850s. In 1856 he returned to one of his earliest pieces of furniture, the Blackburn-Broyles sideboard. As mentioned, he also built a pulpit for the Pleasant Hill Methodist Church. When the church was demolished in 1906 to make way for a larger building, a note was found inside a column stating “this memorandum has been deposited in the column in which it will be found to tell future generations when the Pleasant Hill Meeting House was erected and the pulpit was completed… Written and deposited by John C. Burgner, this 7th day of December, 1858.”[77]

Burgner’s relationship with his ex-wife Eliza apparently remained complicated. On 4 June 1860 a Federal Census taker listed her in John C. Burgner’s household in Washington County, Tennessee. The next month, on 26 July 1860, another census taker, working near Waynesville, Haywood County, North Carolina, found her living along with her two sons David and Walter, who was then identified as a silversmith. David Burgner was born circa 1845, during Eliza Burgner’s affair with James Love.

How and why his ledger book remained in North Carolina—where it now resides in the Haywood County Historical & Genealogical Society’s collection—is unknown. Burgner may have abandoned the book in North Carolina during his rapid departure for Tennessee in the wake of his wife’s infidelity. Supporting that theory is the fact that the last entry in the book is from 1844, when Burgner was still living in Haywood County and before his return to Tennessee. A more poignant bit of evidence that points to Burgner abandoning his ledger book in the midst of his wife’s affair is a page in the center of the book, where Burgner wrote his name, the date 24 June 1848, and the revealing couplet:

Never mary [sic] without love

and love without reason.[78]

John C. Burgner died in 1863 in Washington County, Tennessee.

Furniture Forms Produced in the John C. Burgner Shop

The survival of only two desks and a few sideboards attributed the shop of John C. Burgner presents a skewed perspective of his shop’s actual production. Burgner’s wastebook—which accounts for more than a thousand pieces of woodwork created between 1820 and 1844—helps us to more accurately understand the full scope of work and broad range of furniture forms produced by his shop. The ledger also reveals how Burgner’s shop met the furniture demands of southern Backcountry consumers of both modest and expansive means.

The two surviving desks might lead to an assumption that a great many desks were produced. The waste book, for example, records simple writing desks costing $3.50, “counter desks” that cost $5, and a “pine writing desk” costing $20 made for TJ Avery in 1835.[79] In addition, in 1830 Burgner recorded making a more elaborate and expensive “selindrical [sic] desk & bookcase” for $85 as well as a “French Secretary” costing $45 for J. Erwin in 1834.[80] When viewed in total, the waste book reveals that only 3 percent of Burgner’s shop output was associated with desks (Figure 39).

Even more illustrative of this skewed perspective is that there are more sideboards attributed to John C. Burgner’s shop than any other furniture form, but work related to sideboards accounts for just 2 percent of the total waste book entries (see Fig. 39). Nevertheless, the entries for sideboards give us an excellent perspective on the variety of forms produced in the Burgner shop for its Backcountry clientele. Two categories of sideboards are recorded in the waste book: slab sideboards and regular sideboards. Presumably slab sideboards stand on tall turned legs (Figure 40) while regular sideboards with more storage sit closer to the ground (Fig. 6). Slab sideboards cost half as much as regular sideboards, starting as low as $8 versus $16 for the least expensive regular sideboard.[81] However, depending on options, a slab sideboard could cost as much as $30.[82]

Regular sideboards presented the opportunity for greater customization and, therefore, higher cost. In 1831 Burgner recorded a “fancy top sideboard” for $125.[83] The two highest priced items recorded in the waste book were “one sideboard & chiny press” made in 1829 that cost $200.50 and John Rutherford’s 1835 sideboard that cost $200.[84] Just one year after Rutherford took delivery, Burgner charged yet another $50 for “work done upon J. Rutherford’s sideboard.”[85]

Some of the most surprising woodworking forms to be found in the Burgner waste book were musical instruments. As discussed, the Blackburn-Broyles sideboard (Fig. 6) and the Patton desk (Fig. 9) both contain musical instruments (zithers). The waste book records that Burgner also made four dulcimers: two in 1823 for $3 each; one in 1827 for $12; and one in 1833 for $6.[86] The range in prices may indicate that Burgner was capable of making both mountain and hammer dulcimers.[87] The waste book also records that his brother Jacob Forney Burgner repaired a “pianoforty” in 1831 for $30. Musical talent ran in the family, as John C. Burgner’s youngest brother Daniel Forney Burgner was granted a patent for a violin in 1892 (Figure 41).[88]

Not unexpectedly, the Burgner waste book reveals that the shop also made some of its own tools. Shortly after he relocated to Morganton, North Carolina, Burgner made “Two Work Benches” valued at $15. In 1826 his brother Henry Burgner made “one Cutting box” for the shop at a cost of $2.50.[89] Planes are the most common tools found in the waste book: In 1822 the shop produced “one set of double bit bench planes” for $5 and a year later “one set of bench planes” for $8.[90] In January 1829, John C. Burgner recorded that he made “half dozen bench planes” at a value of $10.[91] Occasionally the waste book is more specific about the type of plane produced, for example, Henry Burgner produced “one Pointer plane” valued at $8 in 1826 while his brother produced “one Smoothing plane” in 1834 valued at $1.25.[92]

By far the most common furniture forms made in the Burgner shop were tables and stands. The waste book documents 282 tables and stands, which comprised 28 percent of the total recorded shop output (see Fig. 39). They ranged widely in price. Washstands could be had for as little as $1 or cost as much as $10.[93] Tables from the Burgner shop cost as little as $1.25.[94] Occasionally Burgner specified a table’s wood. In 1833 he sold three pine tables for just $1 each and in 1844 he sold “one poplar table” for $1.25.[95] Sewing tables ranged from $3 to $10.[96] Elliptical tables started at $10.[97] In July 1829 he sold a “pillar and claw table” for $25.[98] The most expensive table recorded in the wastebook was the “1 set tables”—probably a multi-part dining table—made by his journeyman A.H. Campbell for a member of the Erwin family for $50.[99]

The next most common furniture form was the chest of drawers. Burgner’s shop produced 188 commodes, dressing boards, dressers, and bureaus, for 19 percent of the total output (see Fig. 39). In 1827 Jacob Forney Burgner made “One rough dresser” for $2 and “one small dresser” for $2.50 for his brother’s shop.[100] Six years later, journeyman Henry Spainhower was recorded making “one pine dresser” for $6.[101] Bureaus, the most common subcategory, started at $8 but could cost as much as $50.[102] “Dressing Boards” ranged from $15 to $75 while commodes cost between $40 and $80.[103] Interestingly, demand for chests of drawers appears to have been higher among Burgner’s Tennessee clientele on Horse Creek than with his North Carolina customers in Morganton. While chests of drawers made up 31 percent of Burgner’s shop output in Horse Creek, they were only 17 percent of his total output in Morganton.

Miscellaneous work accounted for a great deal of Burgner’s shop production, particularly in Morganton. Shortly after arriving in North Carolina he charged $1 for making an umbrella staff and $8 to make “one grind stone fraigm [sic].”[104] That same year he charged $6 for making “one hat press” and fifty cents the following year for making “one Hatters press basket.”[105] In 1826 he charged fifty cents to make a set of quilting frames.[106] In 1828 his brother Henry Burgner is recorded making “one Shandeleer [sic] for $1.50.”[107] Another brother, Jacob Forney Burgner, made “one dough trough and rolling pin” in 1832 valued at $1.50.[108] Three years later John C. Burgner made “2 pound cake Stands” for merchant Thomas Walton for fifty cents.[109] Though John C. Burgner never recorded making a frame in Horse Creek, “picture”, “painting”, and “portrait” frames accounted for 3 percent of his work in Morganton. A “painting frame” could be had for as little as $1 while his most expensive frames could cost as much as $5.[110] In 1831 Samuel Tate paid $1.50 for “one portrate [sic] frame” and four years late he purchased two “picture frames” for $3.50 each.[111]

The objects and work recorded in John C. Burgner’s waste book aid in correcting what might otherwise be an erroneous understanding of his cabinetmaking shop’s output. The surviving desks and sideboards attributed to his shop suggest an intensive production of case furniture. In reality, the Burgner shop produced more tables and stands than any other furniture form and relied heavily on miscellaneous work to earn income. Burgner’s shop output was probably not atypical in the early southern Backcountry. It serves as an unfiltered account of the furniture forms and woodworking services demanded by consumers in an early-nineteenth-century southern Backcountry market.

Conclusion

John C. Burgner’s ledger—both the account book and waste book—reveal that his customers in Tennessee’s Nolichucky River Valley included some of the most prominent names in region.[112] Moving to the North Carolina county seat of Morganton, Burgner quickly acquired patronage from members of the county’s most powerful families, among them the Forneys, Tates, and Erwins.[113] Burgner maintained a well-to-do clientele when he relocated to Waynesville, North Carolina, where among his customers was the wealthy resident James R. Love, the man who would steal the heart of Burgner’s wife, Eliza.[114]

Less familiar names appear in the ledger book as well: the farmers and workers of East Tennessee and Western North Carolina of more modest means. Burgner’s shop relied heavily on purchases of the common tables, stands, and miscellaneous items that accounted for the majority of his business. Meeting the furniture needs and aspirations of all his customers, both rich and poor, was necessary to the success of Burgner’s cabinetmaking enterprise.

The ledger also documents a community of craftsmen. Over the period covered by the waste book more than twenty apprentices and journeymen worked in Burgner’s shop. Two of those men were his younger brothers, Henry and Jacob Forney Burgner, who returned home to farming and cabinetmaking in East Tennessee. Others, following their time working in John C. Burgner’s shop, took their skills west as part of the great wave of westward migration that defined nineteenth century America, setting up shops in Arkansas, Iowa, and Kentucky.

When looked at in total, the ledger book kept by John C. Burgner is perhaps the most comprehensive document of a cabinetmaker working during the first half of the nineteenth century in the southern Backcountry—and quite possibly in the entire South. It is a document that illuminates both furniture and people. It tells the story of birth and death, as well as love and loss. And Burgner’s ledger book stands as a testament to the importance and persistence of family and community in the rural American South.

The John C. Burgner ledger in its entirety can be viewed and downloaded as a PDF document by clicking here.

The author gratefully dedicates this article to the incomparable Mary Jo Case. Without her inspiration and assistance this article would never have existed.

Daniel Kurt Ackermann is the Curator of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts. He can be contacted at [email protected].

[1] Thomas Elfe Account Book, 1768–1775, Manuscripts (#49), Charleston Library Society, Charleston, SC; see also Mabel L. Webber and Elizabeth H. Jervey, comps., “The Thomas Elfe Account Book, 1768–1775,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, Vols. 35–42 (1934–1941).

[2] John C. Burgner, Ledger Book, 112-115, Haywood County Historical & Genealogical Society, Waynesville, NC. Photocopy of the original deposited in the MESDA Research Center, Winston-Salem, NC. The ledger in its entirety can be viewed and downloaded as a PDF document by clicking here.

[3] Call No. TT 197 B8, Anne P. and Thomas A. Gray Library, Old Salem Museums & Gardens, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

[4] “Burgner Family Tree,” unpublished manuscript, n.d., Dickson-Williams Mansion, Greeneville, Tennessee.

[5] The 1850 Federal Census lists both Christian Burgner and Daniel Burgner as cabinetmakers living in Greene County, Tennessee.

[6] Ralph Beaver Strassburger and William John Hinke, Pennsylvania German Pioneers: A Publication of the Original Lists of Arrivals in the Port of Philadelphia from 1727 to 1808 (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing, 1966), 328.

[7] Personal correspondences of the author with Walter C. Burgner (family historian), 2015; Memorial for Peter Burgner Sr., www.findagrave.com, memorial 141882748 (online: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=141882748 [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[8] Jacob Burgner, History and Genealogy of the Burgner Family: In the United States of America, as Descended from Peter Burgner, a Swiss Emigrant of 1734 (The Oberlin News Press, 1890) 3; Commemorative Biographical Record of the Counties of Sandusky and Ottawa, Ohio: Containing Biographical Sketches of Prominent and Representative Citizens (J.H. Beers & Company, 1896), 456.

[9] Christian Burgner and Anna Barbara Bowman Burgner had four children. Christian Burgner died unexpectedly in 1753 or 1754, leaving no will. Administration of the estate fell to his brother Peter Burgner. Under court order, Peter sold his brother’s 160 acres for £139.10.0 to support the couple’s four children, Peter (1748–1824), Christian Peter (b.1750), Hans (b.1751), and Barbara (b.1753). Special consideration for Christian Burgner’s children was also made by their paternal grandfather Peter Burgner. When Peter Burgner the elder died in 1768, he divided his estate between his three surviving children with a forth share plus five shillings divided between the four children of his eldest son Christian who predeceased him. Personal correspondences of the author with Walter C. Burgner (family historian), 2015; Memorial for Christian Burgener Sr., www.findagrave.com, memorial 141853645 (online: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=141853645 [accessed 22 May 2015]); Register of Wills, Lancaster County Courthouse, Book Y, Vol. 2, p. 33; Memorial for Peter Burgnener Sr., www.findagrave.com, memorial 141882748 (online: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=141882748 [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[10] Christian Peter Burgner married Anna Maria Burkhart (1755–1815) in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania in 1771; the couple had at least six children (Memorial for Christian Burgner Sr., www.findagrave.com, memorial 141841561 [online: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=141841561 {accessed 22 May 2016}]). For Christian Peter Burgner’s military career, see Sons of the American Revolution Membership Applications, 1889–1970 [Louisville, KY: National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, microfilm), membership no. 84853 (available online: http://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=2204 {accessed 22 May 2016}]).

[11] Personal correspondences of the author with Walter C. Burgner (family historian), 2015; Memorial for Christian Burgner Sr., www.findagrave.com, memorial 141841561 (online: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=141841561 [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[12] John Vogt and T. William Kethley, Shenandoah County Marriage Bonds, 1772–1850 (Athens, GA: Iberian, 1984), 60.

[13] “Burgner Family Tree,” unpublished manuscript.

[14] Early Tennessee/North Carolina Land Records, 1783–1927, Record Group 50, Warrant No. 1571, Division of Archives, Land Office, and Museum, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, TN (available online: http://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=2882 [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[15] On 1 January 1812, “Peter Burgner of the State of Tennessee Greene County” sold his two hundred acres in Washington County to Jacob Spore for $1000.” Washington County (Register of Deeds), Deed Book 13, pp. 295-296 (microfilm roll # 198, Vol. 11-14 [Aug 1806–Nov 1815], Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, TN).

[16] Washington County (Register of Deeds), Deed Book 13, 288-289.

[17] For more information about settlement in the Nolichucky River Valley see: MTSU Center for Historic Preservation, “The Transformation of the Nolichucky Valley, 1776-1960, Greene and Washington Counties,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination, 2001 (online: http://focus.nps.gov/pdfhost/docs/NRHP/Text/64500763.pdf [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[18] Will Thomas Hale and Dixon Lanier Merritt, A History of Tennessee and Tennesseans: The Leaders and Representative Men in Commerce, Industry and Modern Activities (Chicago, IL: Lewis Publishing, 1913), 792.

[19] Richard Price Nye, Holston Methodism: From Its Origin to the Present Time, (Nashville, TN: Methodist Episcopal Church South, 1912), Vol. I, 186.

[20] Christian Peter Burgner’s youngest daughter was baptized in the Old Reformed Lutheran Church at Funkstown, Maryland, in 1781. Personal correspondences of the author with Walter C. Burgner (family historian), 2015; Memorial for Christian Burgener Sr., www.findagrave.com, memorial 141853645 (online: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=141853645 [accessed 22 May 2015]).

[21] Jacob Burgner, History and Genealogy of the Burgner Family: In the United States of America, as Descended from Peter Burgner, a Swiss Emigrant of 1734 (Oberlin, OH: Oberlin News Press, 1890), 167; Marvin French, “Ancestors of Margaret Amanda Burgner” (online: http://lajollabridge.com/French/ufo/Gentry-French-Wives.pdf [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[22] Francis Asbury, The Journal of the Rev. Francis Asbury: Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church (New York: N. Lane & Scott, 1852) Vol. II, 93 and Vol. III, 34; John Walter Wayland, A History of Shenandoah County, Virginia (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing, 1969), 425, 483–484.

[23] “Historical Tidbits Relating to Pleasant Hill Methodist Church, Horse Creek Community,” The Greene County Pioneer, Vol. II, No. 3 (September 1986), 86.

[24] Will of Peter Burgner, 21 May 1824, Greene County Court Minutes 1824-1825, 120 (transcript available online: http://www.genealogy.com/ftm/f/r/e/Marvin-L-French/WEBSITE-0001/UHP-0092.html [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[25] Records of the 1820 Census of Manufactures, Eastern District of Tennessee, Roll 26, United States National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC; cited from John Mathews, MESDA Craftsman Database, ID No. 23238 (online: http://www.mesda.org/research_sprite/mesda_craftsman_database.html [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[26] The 1850 Federal Census recorded Mathews as living in Greene County and listed him as being born in Maryland. He was living with his wife Amy Earnest Mathews, their three children, and a young man named Valentine Harris, identified as a cabinetmaker, who could have been a journeyman or possibly an apprentice working in Mathew’s shop.

[27] Burgner, Ledger Book, 5-6; Tennessee State Marriages, 1780-2002, John Matthews and Amy Earnest, 11 April 1835, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, TN (available online: http://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1169 [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[28] Burgner, Ledger Book, 1-4.

[29] Audio recording of the zither in the sideboard illustrated in Fig. 9 courtesy of the Tennessee State Museum, Nashville, TN.

[30] Charles C. Dawson, A Collection of Family Records (Albany, NY: 1874), 270 (available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=dWVfrEWbMRYC [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[31] Burgner, Ledger Book, 5-6, 144.

[32] Dawson, A Collection of Family Records, 270 (available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=dWVfrEWbMRYC [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[33] Ibid, 143; Will of Peter Burgner (transcript available online: http://www.genealogy.com/ftm/f/r/e/Marvin-L-French/WEBSITE-0001/UHP-0092.html [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[34] Burgner, Ledger Book, 13-14.

[35] Will of Peter Burgner (transcript available online: http://www.genealogy.com/ftm/f/r/e/Marvin-L-French/WEBSITE-0001/UHP-0092.html [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[36] Burgner, Ledger Book, 139.

[37] Ibid, 138.

[38] John Hill Wheeler, Historical Sketches of North Carolina… (Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Grambo and Company, 1851), 241-243 (available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=uPxHAQAAMAAJ [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[39] For Peter Forney, see Burgner, Ledger Book, 47-48, 115; for Jacob Forney, see Burgner, Ledger Book, 109, 110.

[40] North Carolina Department of Archives and History, “Ingleside,” Lincoln County, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 5 November 1971 (available online: http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/NR-PDFs.html [accessed 22 May 2016]); Wheeler, Historical Sketches of North Carolina…, 245 (available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=uPxHAQAAMAAJ [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[41] Burgner, Ledger Book, 47-48.

[42] North Carolina Department of Archives and History, “Jacob Forney Jr. House,” Burke County, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 5 April 1976 (available online: http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/NR-PDFs.html [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[43] Burgner, Ledger Book, 136-138.

[44] The tabletop secretary bookcase may have originally belonged to Jacob Forney Jr. or his son James Harvey Forney (1815–1879).

[45] Edward William Phifer, Burke: The History of a North Carolina County, 1777-1920, With a Glimpse Beyond, rev. ed. (Morganton, NC: Phifer, 1982), 53; for Forney Family members, see Burgner, Ledger Book, 47-48; for Tate Family members, see Burgner, Ledger Book, 29-30, 45-46, 55-56, 65-66, and 81-82; for Erwin Family members, see: Burgner, Ledger Book, 17-18, 31-32, 43-44, 49-50, 51-52, and 55-56.

[46] Ibid, 21-22, 137.

[47] Ibid, 136.

[48] Greene County Circuit Court Minutes, 1849–1852, p. 407, T. Elmer Cox Historical and Genealogical Library, Greeneville, TN.

[49] Burgner, Ledger Book, 127.

[50] Greene County Circuit Court Minutes, 1849–1852, p. 407, T. Elmer Cox Historical and Genealogical Library, Greeneville, TN; 1850 Federal Census; 1860 Federal Census.

[51] Burgner 126

[52] Phifer, Burke: The History of a North Carolina County, 417.

[53] Ibid, 343–345.

[54] Burgner, Ledger Book, 114.

[55] Ibid, 113.

[56] Phifer, Burke: The History of a North Carolina County, 344.

[57] “Francis Silver’s Confession,” Lenoir Topic (Lenoir, NC), 24 March 1885, as quoted in Daniel W Patterson, A Tree Accurst: Bobby McMillon and Stories of Frankie Silver (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, 2000), 102-103.

[58] Ibid, 103–104.

[59] “Francis Silver’s Confession” Lenoir Topic (Lenoir, NC) 5 May 1886, as quoted in Perry Deane Young, The Untold Story of Frankie Silver: Was She Unjustly Hanged? (Asheboro, NC: Down Home, 1998), 113.

[60] The author is indebted to Bob and Norma Noe and Mack and Sharon Cox for generously sharing their research on Henry Spainhower. Burgner, Ledger Book, 121, 114; N. P. Spainhower, “Obituary—Henry Spainhower,” Neoga News (Neoga, IL), n.d [ca. 1901]; Sharon Hamilton, “Henry Spainhower: Master Craftsman Left a Rich Legacy,” Paint Lick Reflections, Spring 2003; “Many Antiques Adorn Homes of Kentuckians, the Workmanship of Henry Spainhower,” On the Garrard County Line (Garrard County Historical Society), November 2007.

[61] John C. Burgner recorded in his waste book that “Davenport Ranaway” on 6 March 1831.

[62] For A.H. Campbell, see Burgner, Ledger Book, 104, 93-94; for Samuel Capeheart see 114; for David Dellinger see 112; for Henry Long see 116; for R.C. Spears see 112, 109, 77-78, 91-92; for James Taylor see 110, 79-80.

[63] Ibid, 112, 109

[64] 1850 Federal Census

[65] Fay Hempstead, Historical Review of Arkansas: Its Commerce, Industry and Modern Affairs (Chicago, IL: Lewis Publishing, 1911), Vol. III, 1348 (available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=hD9EAQAAMAAJ [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[66] North Carolina Land Grant, No. 19704, 8 February 1833, microfilm call # S.108.160.38N frame 689, State Archives of North Carolina, Raleigh, NC (available online: http://www.nclandgrants.com/home.htm [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[67] Burgner, Ledger Book, 95-96.

[68] Namuni Hale Young, Art & Furniture of East Tennessee (Knoxville, TN: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1997), 37.

[69] Ozey and Sarah Broyles were neighbors of Christian Burgner and possibly John C. Burgner before he left the Nolichucky River Valley. The Broyleses and Christian Burgner were listed on the same page in the 1850 Federal Census.

[70] Donald L. Winters, Tennessee Farming, Tennessee Farmers: Antebellum Agriculture in the Upper South (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 1994), 68-69; James Gray Smith, A Brief Historical, Statistical, and Descriptive Review of East Tennessee, United States of America: Developing Its Immense Agricultural, Mining, and Manufacturing Advantages (London: J. Leath, 1842), 9; Burgner, Ledger Book, 97-98.

[71] The men are identified as “R Morrow,” “EA,” and “J Yarborough.” Of the three, the John Wesley Yarborough (1828–1897) can be identified with any certainty. Burgner, Ledger Book, 103-102; Memorial for John Wesley Yarborough, www.findagrave.com, memorial 32231157 (online: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=32231157&ref=acom [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[72] Burgner, Ledger Book, 99-100.

[73] Greene County Circuit Court Minutes, 1849–1852, 408-411

[74] Burgner, Ledger Book, 102.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Gravestone for Maria Williamson Comen Love, Green Hill Cemetery, Waynesville, Haywood County, NC (online: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=102189897 [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[77] “Historical Tidbits Relating to Pleasant Hill Methodist Church, Horse Creek Community,” The Greene County Pioneer, Vol. 2, No. 3 (September 1986), 86.

[78] Burgner, Ledger Book, first leaf.

[79] Ibid, 105, 124, 106.

[80] Ibid, 111.

[81] Ibid, 132, 118.

[82] Ibid, 136.

[83] Ibid, 125.

[84] Ibid, 130, 105.

[85] Ibid, 105.

[86] Ibid, 140, 135, 113.

[87] The author is grateful to Mike Bell, furniture curator at the Tennessee State Museum, for his observations on Burgner’s musical instruments.

[88] Patent issued to Daniel F. Burgner, VIOLIN, No. 483,897, Patented 4 October 1892, United States Patent Office, Washington, DC (available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US483897A [accessed 22 May 2016]).

[89] Burgner, Ledger Book, 137.

[90] Ibid, 141, 140.

[91] Ibid, 128.

[92] Ibid, 137, 107.

[93] Ibid, 115, 139.

[94] Ibid, 128.

[95] Ibid, 131, 102.

[96] Ibid, 144, 135.

[97] Ibid, 128.

[98] Ibid, 129.

[99] Ibid, 104.

[100] Ibid, 135.

[101] Ibid, 114.

[102] Ibid, 122, 134.

[103] Ibid, 130, 127, 125, 133.

[104] Ibid, 138.

[105] Ibid, 138, 136.

[106] Ibid, 136.

[107] Ibid, 133.

[108] Ibid, 124.

[109] Ibid, 106.

[110] Ibid, 113, 132.

[111] Ibid, 119, 106.

[112] For Broyles Family members in the account book see Burgner, Ledger Book, 3-6; for Earnest Family members see Ibid, 5-6.

[113] For Forney Family members in the account book see Burgner, Ledger Book, 47-48; for Tate Family members see Ibid, 29-30, 45-46, 55-56, 65-66, 81-82; for Erwin Family members in the account book see Ibid, 17-18, 31-32, 43-44, 49-50, 51-52, 55-56.

[114] Burgner, Ledger Book, 99-100.

© 2016 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts

![Fig. 3: “A Map of the State of Tennessee…,” 1832, surveyed and published by Matthew Rhea (Columbia, TN), engraved by H.S. Tanner, E.B. Dawson, and J. Knight (Philadelphia, PA). Ink on paper; HOA: 34-5/8”, WOA: 68-1/2”. Collection of the Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, G3960 1832 .R4, Washington, DC (available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2011588000/ [accessed 22 May 2016]).](/files/Ackermann_Burgner_Fig_03_Thumb.jpg)