The Moravian town of Salem serves as a microcosm of the American architectural experience. From its roots in the Old World Germanic style to the early American period designs, Salem’s architecture is as varied as the people who contributed to its built landscape. Celebrating the 250th anniversary of the founding of Salem, this article presents biographical sketches of many of the talented and industrious craftsmen who created the town out of the wilderness and continued to shape its architectural legacy well into the nineteenth century.The sixty-five biographies included here are of men—black and white; free and enslaved—who could be determined through the historical record to have left a lasting mark on the buildings of Salem.[1]

Click Here to Browse Salem Craftsmen Alphabetically by Name

Click Here to Browse Salem Craftsmen by Trade

Introduction to Salem and the Moravians

The Unity of Brethren—better known in English-speaking regions as “Moravians” for their origins in the central European land of Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic)—is a Protestant denomination that traces its origins to the fifteenth-century martyr John Hus. After centuries of persecution, in the early eighteenth century the Moravians were able to find a sponsor and home in Herrnhut, Germany on the estate of Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf. Under Zinzendorf’s leadership, the Moravians greatly expanded their missionary activities outward from Herrnhut across Europe, the British Isles and into the New World.

In these new communities the Moravians could freely follow their communal, pacifist, and religion-centered way of life and carry the gospel to potential converts. The church strictly controlled both the spiritual and secular matters in its communities. Several committee boards in each town oversaw and kept extensive records of its congregation’s activities, including religious affairs, marriages, education, occupations, business operations, and communal needs such as roads, water, and community buildings. Of most importance to the building trades was the Aufseher Collegium (board of supervisors) that oversaw the financial and material business of the town.

At the core of Moravian congregations were the choirs, or groups bonded by age, gender, or marital status. Members of each choir came together, and sometimes lived together, for spiritual growth as well as sharing responsibilities of life within the church and town. Choirs included the Single Brothers, Single Sisters, Married Brothers, Married Sisters, Widowers, Widows, Older Boys, Older Girls, Little Boys, Little Girls, and Infants.

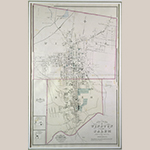

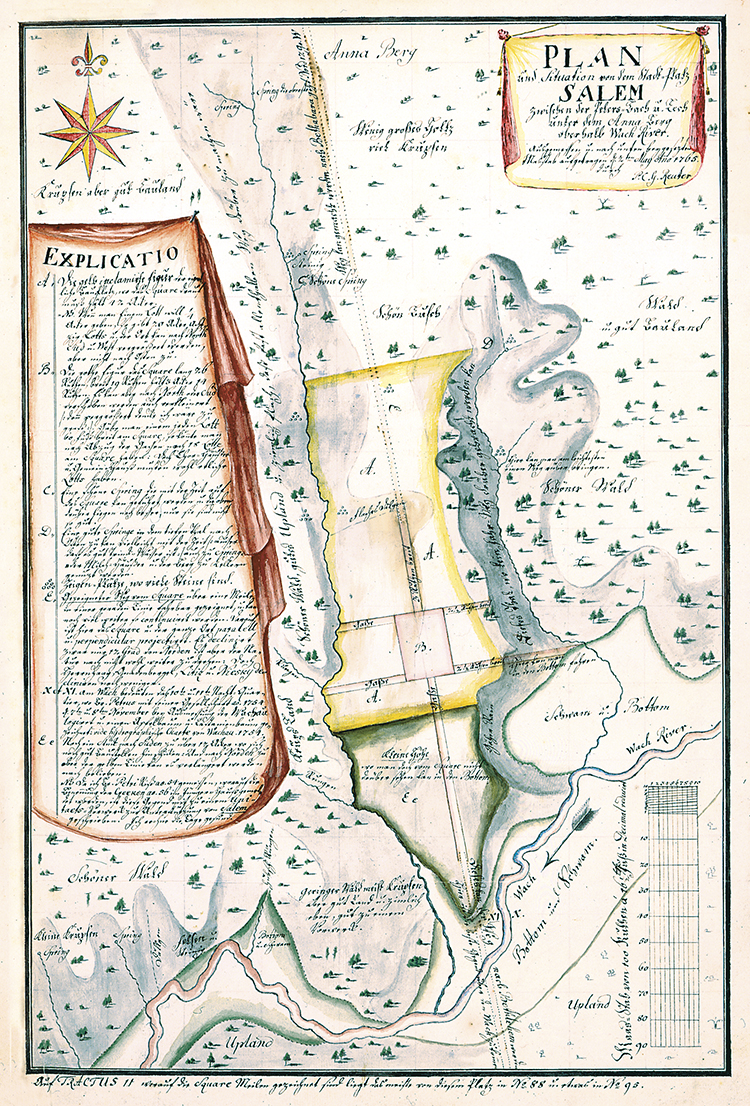

In 1753 the Moravians purchased approximately 100,000 acres of land in Piedmont North Carolina from the colony’s proprietor, John Carteret, the Earl of Granville. They named this tract Wachau after the location of Count Zinzendorf’s ancestral estate along the Danube River in the Wachau Valley of Austria. Later the name was Latinized to “Wachovia.” The Wachovia Tract is the site of present-day Winston-Salem and much of Forsyth County, North Carolina (Figure 1).

Church leaders in the Moravian town of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania nearly immediately began sending settlers to establish communities in the Wachovia Tract. The first town was Bethabara followed by Bethania, established in 1759 (Figures 2 and 3). A central trade and administrative town in Wachovia, to be named Salem, had been planned from the very beginning, but the French and Indian War (1754–1763) greatly disrupted and delayed actual site preparation and construction.

In 1763 Frederick William Marshall was named chief administrator of Wachovia, arriving in Bethabara the following year. He stated his mandate succinctly by announcing that the “founding of a new town in Wachovia was the chief object of his visit.” The next months were spent inspecting various sites until a final selection was made on 14 February 1765. With his objective completed, Marshall left Wachovia a week later and returned to Pennsylvania and then sailed for Europe. In his place, Marshall appointed Johannes Ettwein in charge of preparing to develop the new town of Salem.

Eight men relocated from Bethabara to the site of Salem in February 1766 to begin construction. They were George Holder, Niels Petersen, Jens Schmidt, Gottfried Praetzel, John Birkhead, Jacob Steiner, Melchior Rasp, and Michael Ziegler. In two wagons they brought brick and tile for roofing. Following Old World traditions, whenever possible the Moravians employed clay tiles made by a potter to roof their principal buildings. Many of other essential materials were prepared in Bethabara’s workshops and sent to Salem.

Although he was absent from Wachovia, Marshall clearly articulated his vision for the town of Salem in his correspondence to Ettwein. In a July 1765 letter sent from Bethlehem, Marshall covered the spectrum from the broadest philosophical purpose of the town down to its smallest details. He explained, “This town is not designed for farmers but for those with trades.” The purpose of Salem, he wrote, was to be:

more like a family where the religious and material condition of each person is known in detail, where each person receives the appropriate choir oversight, and also assistance in consecrating the daily life. This must be considered in deciding the form of the town plan.

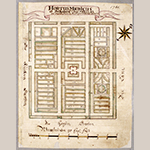

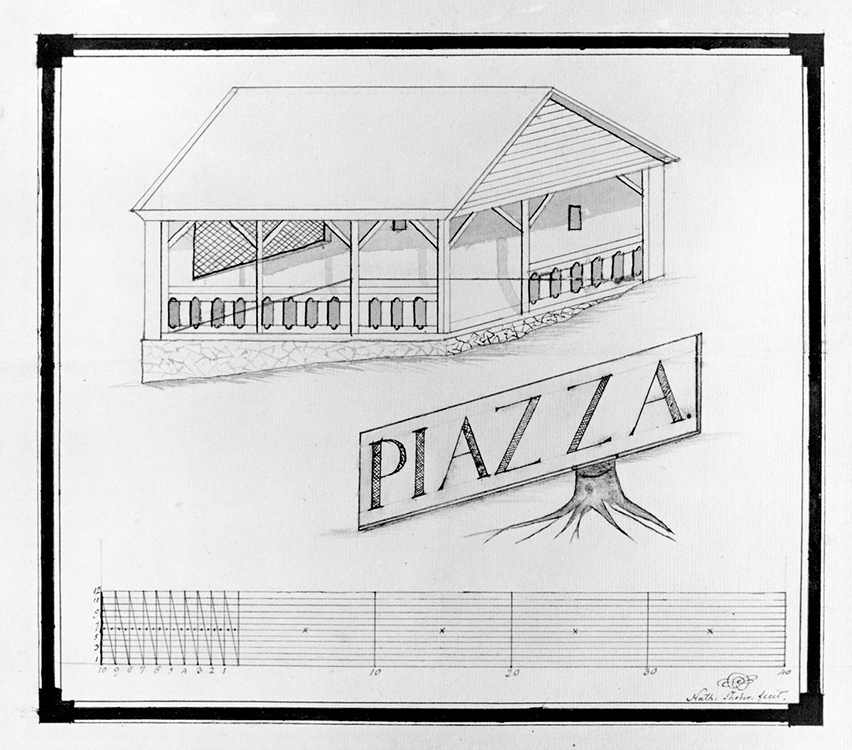

For Salem, Marshall drew extensively from the example of Lititz, Pennsylvania, developed by Moravian surveyor Christian Gottlieb Reuter, which had a standard lot size of sixty-six by four hundred feet and street widths of sixty feet for the main street and forty feet for others, all arranged on a grid pattern (Figure 4). Around a central square he proposed the major congregational buildings. With an eye for the overall appearance of Salem, Marshall suggested “to keep the plan symmetrical the store might be placed on the lower corner [of the square] since it is larger than a family house.”[2]

In February 1768, Marshall returned to Wachovia to personally “undertake to have houses built for the Single Brethren and for the Single Sisters in Salem as soon as possible… and arrange all things in Salem according to the custom of our Congregation and Choirs in Europe.”

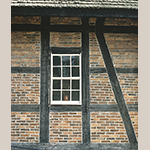

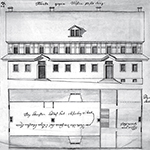

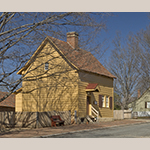

In 1772 the initial construction phase of Salem was completed and the administration of Wachovia moved from Bethabara to Salem, which was also ready for the first permanent residents. The first generation of buildings in Salem, constructed by European-trained artisans such as Melchior Rasp, incorporated Germanic traditions adapted to the local setting and relied chiefly on stone, log, and half-timber (Fachwerk) construction (Figure 5). The use of half-timbering was particularly driven by the difficulty the Moravians found in consistently procuring lime for a strong mortar. Salem’s early masons resorted to using a clay-based mortar that was not stable enough to use in solid brick walls and used half-timbering. Salem’s Single Brothers’ House (Figure 6) and the Fourth House (Figure 7) are half-timbered examples that still stand, restored to their eighteenth-century appearance.

Salem, like many American communities after the Revolutionary War, engaged in a major building campaign. Projects that had been postponed because of the war now took priority. Improved local procurement of lime mortar allowed for solid brick construction of major buildings rather than half-timbering. Old World building traditions in Salem dissipated with the passing of the town’s European-trained craftsmen and the rising influence of those born and trained in America such as Johann Gottlob Krause and Frederick Edward Belo as well as the non-Moravian William Craig.

Aware of these changes in the face of a building boom, Frederick William Marshall prepared a set of “Building Rules” that were enacted in June 1788. More than any other document, the “Building Rules” showed Marshall’s concern for community planning as integrated with both spiritual and secular well-being. The document covers all aspects of the built environment and shows Marshall’s deep understanding of architecture, building trades, and town planning.

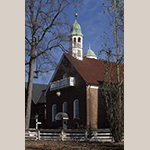

Marshall continued to shape the architecture of Salem into the last decade of the eighteenth century. In 1794 he supervised the design of the Salem Boys’ School (Figure 8). In April 1797 Marshall undertook his crowning architectural achievement, Home Moravian Church (Figure 9). The imposing brick building combines fine Flemish bond brickwork and a traditional Moravian plastered cornice with tall, arched windows and other motifs reflective of the nationally and internationally prevalent taste for neoclassicism. In this building, Marshall introduced an apparently original entrance treatment: an arched hood that became a distinctive and lasting feature of Salem architecture and was revived early in the twentieth century as part of a local Moravian or Salem Revival style.

The Moravian town of Salem would undergo profound changes in the nineteenth century as the church was gradually compelled to loosen control over the daily life of the congregation. A growing American individuality was taking root among Salem’s citizens and conflict with the Moravian theocracy was inevitable. This dynamic emerged architecturally in the form of small workshops built near private houses where Salem’s craftsmen plied their trade rather than in the communal Single Brothers’ House. Examples of this trend include the Schultz House and Shop (Figure 10) and Timothy Vogler House and Shop (Figure 11). Stylistically, rather than harkening back to European traditions, Salem’s builders continued to embrace broader national tastes in features such as Flemish bond brickwork, end chimneys, and central hall plans seen on statement structures like the Vierling House (Figure 12) and John Vogler House (Figure 13).

During the 1830s, advances in technologies and a cotton boom in the South expanded Moravian businesses to dramatic new heights. Factories making wagons and textile mills brought not only immense wealth but also outside investors and ideals. In 1849 the state of North Carolina created Forsyth County with Salem intended to be the site of the county courthouse. Salem’s church administrators successfully resisted the plan by selling approximately fifty acres of land just north of Salem for a new town to be named Winston that would serve as the county seat (Figure 14).

The tensions between sacred and secular in Salem finally came to a head in 1856 when the church council voted to abolish the lease system that had prohibited residents who were not members of the Moravian congregation from owning property in the town and conducting businesses as individuals. This marked the end of the Moravian Church’s governance of the town of Salem as a theocracy. In December 1856 the town officially became an incorporated municipality and elections were held for mayor and eight town commissioners.

The towns of Salem and Winston co-existed through the American Civil War but Reconstruction brought an end to the growth and prosperity that Salem enjoyed for much of the nineteenth century. In contrast, Winston’s tobacco and textiles industries, led by the Reynolds and Hanes families, grew into national empires. In 1913 the two towns were officially consolidated to form the city of Winston-Salem (Figure 15).

The historic buildings and streetscapes of Salem were in serious decline by the 1940s and threatened by obliteration through urban growth. A group of concerned citizens came together in 1947 to study the feasibility of preserving the town’s most important structures. Old Salem was established in 1950 to preserve or restore the historic town of Salem. Through Old Salem’s efforts, the immense talent and effort of the many individuals that created Salem’s built landscape can be experienced and appreciated 250 years after the first tradesman began carving a town out of the wilderness (Figure 16).

Index of Craftsmen by Trade

(presented chronologically by working dates)

| Masons

Melchior Rasp – worked 1755–1784 Abraham Gottlieb Steiner – worked 1758–unknown Christian Renetus Heckewilder – worked 1766–ca. 1774 Johann Samuel Mau – worked 1766–1774 William Gentry – worked 1770–1772 Johann Gottlob Krause – worked 1771–1802 Johann Heinrich Blum – worked 1773–1824 Melchior Fischer – worked 1774–1794 George Fischer – worked 1780–1810 Abraham Hauser – worked 1782–1797 Abraham Loesch – worked 1782–circa 1820 Johann Michael Seiz Jr. – worked 1784-1788 William Volk – worked 1784–unknown William Craig – worked 1794–circa 1820 John David Blum – worked 1802–1842 William Hauser – worked 1802– unknown Pleasant Roberts – worked ca. 1803 |

Carpenters

George Holder – worked 1754–1768 Jacob Steiner – worked 1755-1777 Christian Triebel – worked 1755–1788 Rudolf Strehle – worked 1764-1790 Niels Petersen – worked 1766-1774 David Holzapfel – worked 1770-1856 Melchior Fischer – worked 1726-1798 Martin Lick – worked ca. 1777-1789 Johann Michael Seiz Jr. – worked 1784-1788 Jacob Spach – worked ca. 1786-1856 Charles Alexander Cooper – worked 1831-ca. 1850 |

| Joiners

John Jacob Wohlfarth – worked 1769–1807 Andreas Brosing – worked 1770-1781 George Fischer – worked 1780-1810 Neman van Zevely – worked 1797-1809 Thomas Holland – worked 1802–unknown Magnus Benjamin Hulthin – worked 1805–ca. 1813 Johann Friedrich Belo – worked 1806–1827 Karsten Petersen – worked 1806-1857 Daniel Wohlfarth – worked 1806–ca.1820 Johann Thomas Wohlfarth – worked 1808–1830 Daniel Wolf – worked 1811–1830 Charles Abraham Steiner – worked 1811-1879 Johann Heinrich Keller – worked 1816-1818 Frederick Edward Belo – worked 1827- ca. 1843 George Mumford Swink – worked 1839-1852 |

Turners

Johann George Ebert – worked 1794-1796 Johann Simon Leicht – worked 1805-1812 Peter Fetter – worked 1827–1847 |

| Architects

Frederick William Marshall – worked 1764-1802 Elias Alexander Vogler – worked 1846-1876 |

Surveyors

Christian Gottlieb Reuter – worked 1758-1777 Carl Ludwig Meinung – worked 1772-ca. 1805 Frederick Christian Meinung – worked 1796-1851 |

| Brickmakers

Johann Christoph Schmidt – worked 1755-1799 Peter Stotz – worked 1762-1771 Charles Culver – worked 1766-1767 Cornelius Sale – worked 1776-1788 James Reuben Fletcher – worked 1782 Joseph Essig – worked 1797-1812 |

House Painters

Naeman Benjamin Reich – worked 1840-1846 |

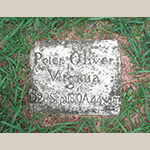

| Enslaved Tradesmen

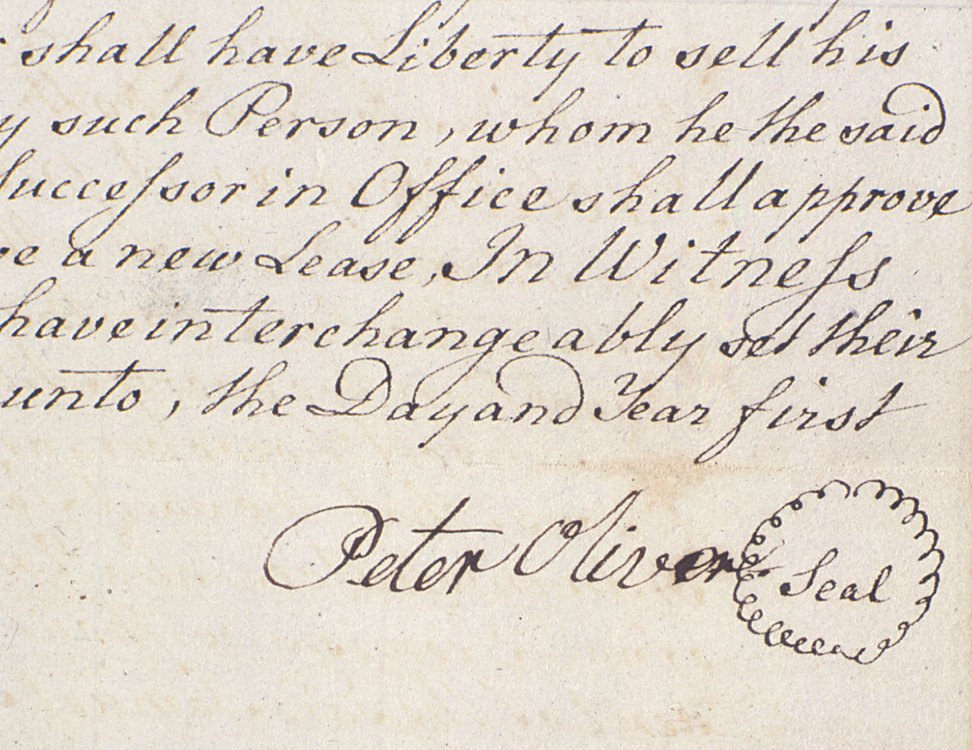

Christian (formerly Frank) – worked 1771-1789 Abraham (formerly Sambo) – worked 1771-1797 Sam – worked 1775-ca. 1790 Champion – worked ca. 1783 Peter Oliver (formerly Oliver) – worked 1784-1809 George – worked ca. 1785 |

Helpers

Erich Ingbretsen – worked 1753-1759 Lorenz Bagge – worked 1764-1783 John Birkhead – worked 1766-1771 Jens Schmidt – worked 1766-1768 |

Index of Craftsmen by Name

(presented alphabetically)

| Abraham (formerly Sambo) – worked 1771-1797

Bagge, Lorenz – worked 1764-1783 Belo, Frederick Edward – worked 1827– ca. 1843 Belo, Johann Friedrich – worked 1806–1827 Birkhead, John – worked 1766-1771 Blum, Johann Heinrich – worked 1773–1824 Blum, John David – worked 1802–1842 Browsing, Andreas – worked 1770-1781 Champion – worked ca. 1783 Christian (formerly Frank) – worked 1771-1789 Cooper, Charles Alexander – worked 1831-ca. 1850 Craig, William – worked 1794–circa 1820 Culver, Charles – worked 1766-1767 Ebert, Johann George – worked 1794-1796 Essig, Joseph – worked 1797-1812 Fetter, Peter – worked 1827–1847 Fischer, George – worked 1780-1810 Fischer, Melchior – worked 1774–1794 Fletcher, James Reuben – worked 1782 Gentry, William – worked 1770–1772 George – worked ca. 1785 Hauser, Abraham – worked 1782–1797 Hauser, William – worked 1802– unknown Heckewilder, Christian Renetus – worked 1766–ca. 1774 Holder, George – worked 1754–1768 Ingbretsen, Erich – worked 1753-1759 Holland, Thomas – worked 1802–unknown Holzapfel, David – worked 1770-1856 Hulthin, Magnus Benjamin – worked 1805-ca. 1813 Keller, Johann Heinrich – worked 1816-1818 Krause, Johann Gottlob – worked 1771–1802 Leicht, Johann Simon – worked 1805-1812 Lick, Martin – worked ca. 1777-1789 |

Loesch, Abraham – worked 1782–circa 1820

Marshall, Frederick William – worked 1764-1802 Mau, Johann Samuel – worked 1766–1774 Meinung, Carl Ludwig – worked 1772-ca. 1805 Meinung, Frederick Christian – worked 1796-1851 Oliver, Peter (formerly Oliver) – worked 1784-1809 Petersen, Karsten – worked 1806-1857 Petersen, Niels – worked 1766-1774 Rasp, Melchior – worked 1755–1784 Reich, Naeman Benjamin – worked 1840-1846 Reuter, Christian Gottlieb – worked 1758-1777 Roberts, Pleasant – worked ca. 1803 Sale, Cornelius – worked 1776-1788 Sam – worked 1775-ca. 1790 Schmidt, Jens – worked 1766-1768 Schmidt, Johann Christoph – worked 1755-1799 Seiz, Johann Michael Jr. – worked 1784-1788 Spach, Jacob – worked ca. 1786-1856 Steiner, Abraham Gottlieb – worked 1758–unknown Steiner, Charles Abraham – worked 1811-1879 Steiner, Jacob – worked 1755-1777 Stotz, Peter – worked 1762-1771 Strehle, Rudolf – worked 1764-1790 Swink, George Mumford – worked 1839-1852 Triebel, Christian – worked 1755–1788 Vogler, Elias Alexander – worked 1846-1876 Volk, William – worked 1784–unknown Wohlfarth, Daniel – worked 1806–ca.1820 Wohlfarth, Johann Thomas – worked 1808–1830 Wohlfarth, John Jacob – worked 1769–1807 Wolf, Daniel – worked 1811–1830 Zevely, Neman van – worked 1797-1809 |

Masons

|

Masons in the Wachovia Tract began their work as soon as the Moravian men arrived laying the foundation for the future. There was no pre-fabricated stone available to them and what they used they pulled from the earth. That said, Piedmont North Carolina is home to several indigenous types of rock that lent itself greatly to building. Granite was quarried throughout the Wachovia Tract and was used by Moravian masons in buildings, providing strong foundations for the homes.

Red clay is predominant in the area, and the selection of the location of Salem was made in part to a nearby large brick-quality source of red clay for the easy procurement of building materials. The most difficult item for the early Moravian masons to procure was lime. The nearest source was north of Wachovia near Pilot Mountain and often took days to requisition, which led to early building delays. Once the trading town of Salem became more sustained, lime was kept in stock and most building delays ceased due to its availability. As time progressed and materials became more uniform, the masons of Salem created finer and finer work with their stucco and painted facades that gave the illusion of large colorful bricks.

Melchior Rasp

Born: 8 January 1715

Died: 19 March 1785

Working: 1755–1784

Residences: Salzburg, Austria; Bethabara, NC; Salem, NC

A master mason in both Bethabara and Salem, Melchior Rasp was among the few European-born building artisans in colonial North Carolina whose structures survive to illustrate the direct transplantation of Old World traditions. From 1754 until 1784 Rasp played a central role in the early architecture of the Moravians in the Wachovia settlement of Piedmont North Carolina. His best-known work is the Single Brothers’ House in Salem (Fig. 6), a nationally important example of traditional European Fachwerk (half-timbered) construction.

Born in Salzburg, Austria, Rasp was employed in the salt works as a youth. He moved to Holland at age fifteen, and subsequently moved to Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, where he learned the mason’s trade. In the early 1740s he settled in the Moravian town of Herrnhaag, joined the Moravian congregation, and worked as a mason for several years. In 1750 he departed for Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where he stayed for five years, with his major work being Nazareth Hall, a massive masonry school building.

Melchior Rasp arrived in Wachovia on 4 November 1755 and his masonry skills were quickly put to use. The Records of the Moravians for 1 December 1755 noted, “During the first half of the month [November] work was pushed on the new house; Pfeiffer [unidentified] and Melchior Rasp, who had been breaking stone, were appointed to build the wall.”

Rasp’s memoir, a record of his life in the Moravian records, noted, “When the building of Salem was begun, he moved thither with the first Brethren and was the master mason in all the work of that town including the Gemein Haus and the [Single] Brothers House. One could be certain that he intended his work to be useful and permanent.” Rasp and other workmen erected a series of initial Salem buildings in traditional European Fachwerk that included the relatively small First House, Second House, Third House, Fourth House, and Fifth House as well as the large Single Brothers’ House and Gemein Haus (Figure 17), the town’s combination church and meeting place.

As master mason, Rasp was responsible for all the stone and masonry construction in Salem and was assisted by apprentices or untrained local workers as available. On 9 April 1777, for example, the tailor and night watchman Henry Zillman was appointed to help Rasp in placing a tile roof on the Gemein Haus in Salem. Rasp also built masonry foundations and chimneys for numerous buildings, such as the 1771 Miksch House (Figure 18), a log structure covered with clapboards, which was the first residence for a single family in Salem. Rasp also built key buildings in other Moravian communities in Wachovia, including the 1770 Gemein Haus in Bethabara and Bethania’s 1777 tannery.

Rasp was plagued with physical mishaps caused, in part, by the nature of his trade. His health was permanently damaged on one of his trips from Bethabara during Salem’s construction when he fell and drove a pipe stem through the roof of his mouth, a wound that incapacitated him for seven weeks. In 1778, when he was working on a new distillery in Salem, he lost an eye in an accident involving a stone chip. The injury left him nearly blind and afflicted him until his death. Rasp’s expertise, however, continued to be invaluable to the community. He served as a member of the waterworks planning committee and he was appointed as one of Salem’s fire inspectors to check fireplace, stove, and chimney construction and usage.

Even as his age and infirmities took their toll, the Moravian community still relied heavily on Rasp as master mason because there was no one to replace him. In 1779 he was given the assistance of Brother Christian Renetus Heckewelder in building the foundations of woodsheds for the Salem Gemein Haus and Single Sisters’ House (Figures 19 and 20), among other tasks. On 23 May 1780, the records noted, “It might help the walls [of the Second House, a half-timbered structure] to plaster them on the outside if we had someone who could do it for Br. Rasp is too old for such work.” Three months later it was recorded, “At this time it is to be considered that Melchior Rasp is to have a hod carrier so that his work will be easier and cheaper.” On 20 March 1781, to help solve the chronic shortage of masons in Salem, Johann Gottlob Krause was released six months early from his apprenticeship as a potter to enable him to learn the mason’s trade from Rasp. In October 1782, after an eighteen-month apprenticeship as a mason, Krause was designated a journeyman with Rasp his master.

By 1784 Rasp could no longer meet the demands of the position of master mason. In a letter of 15 February 1784, Salem administrator Frederick William Marshall lamented, “We are handicapped by the lack of workmen. Our master carpenter, Trieble [Christian Triebel], is in his seventieth year and our master mason Melchior Rasp in his sixty-eighth year, and both are in the sick room. The latter is no longer able to serve at all.” In December 1784, Krause was named master mason, and Rasp died the nineteenth day of the following March, leaving Krause on his own with only four years of training as a mason. For thirty years Melchior Rasp used traditional skills to build the first generations of substantial buildings in Salem, which defined the town’s early character. Johann Gottlob Krause combined the skills of a mason that he learned from Rasp with other techniques to construct the next generation of masonry buildings in Salem.

Click here to read Melchior Rasp’s entry in North Carolina Architects & Builders: A Biographical Dictionary.

Abraham Gottlieb Steiner

Born: 27 April 1758

Died: 22 May 1833

Working: Unknown

Residences: Bethlehem, PA; Salem, NC

One of the first masons in the Wachovia Tract of North Carolina was the Reverend Abraham Gottlieb Steiner. While Steiner served mostly in an official capacity with the church and as a missionary to the Cherokee, he did aid in early masonry projects. His major contribution was building a stone bridge over Muddy Creek, which served as a connector for those who wished to travel from the Moravian towns of Bethabara and Salem. Steiner also aided in projects among the Cherokee in Western North Carolina, though specifics are not noted in the personnel records.

Christian Renatus Heckewilder

Born: 24 June 1750

Died: 1803

Working: 1766–circa 1774

Residences: Mirfield, West Yorkshire, England; Salem, NC; Bethlehem, PA; Hope, NJ

Christian Renatus Heckewilder was an early mason in Salem. He arrived on 11 October 1766 and within a week announced himself eligible for an apprenticeship, which was the purpose of the visit. By the end of October, Heckewilder was apprenticed to Melchior Rasp to begin learning the mason’s trade.[3] Heckewilder assisted on many of Rasp’s projects during this time, including the First House, Second House, Third House, Fourth House, and Fifth House. He completed his apprenticeship by 1770.

Heckewilder did not pursue the mason’s trade though. He became an intermittent helper in the community store and then the schoolteacher in November of 1774. After teaching, he worked full time in the store of Traugott Bagge.[4] In 1780 he moved to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and then Hope, New Jersey, where he worked as a storekeeper until his death.

Johann Samuel Mau

Born: ca. 1752

Died: unknown

Working: 1766–1774

Residences: Salem, NC; Pennsylvania

Johann Samuel Mau arrived in Wachovia in October 1766 and he was quickly indentured to Melchior Rasp as a mason’s apprentice. During this time he learned brickmaking from Brother Merkly.[5] Mau also is noted as laboring in Bethabara as a thresher.[6] In April 1773 Mau completed his apprenticeship and became a journeyman mason.[7] He returned to Pennsylvania in 1774 to work as a mason.

William Gentry

Born: unknown

Died: unknown

Working: 1770–1772

Residences: Salem, NC

William Gentry was a carpenter in Salem in the early 1770s. He worked on several of the first buildings in Salem.

Gentry worked alongside Jens Schmidt and Christian Triebel to determine the location of a bridge over Muddy Creek at the Shallow Ford Road. Gentry was assigned to complete a bridge approximately fifteen feet high by 1 November 1772. This bridge was to be flood proof for at least four years, lest he build another at his own expense. He completed his task of building the half of the bridge on the Salem side of the creek. However the individuals from the Bethabara side had not completed their half, and Gentry was asked to finish the bridge in its entirety.

Johann Gottlob Krause

Entry compiled by John Larson, Vice President of Restoration, Old Salem Museums & Gardens

Born: 18 September 1760

Died: 4 November 1802

Working: 1771–1802

Residences: Bethabara, NC; Salem, NC

Johann Gottlob Krause was the master mason during the construction of the first major brick buildings in the Moravian community of Salem. Representing the first generation of native North Carolina Moravian artisans, Krause introduced construction techniques in the post-Revolutionary era that blended Germanic forms with decorative brickwork adapted from English traditions, and thus shaped the architectural character of this unique community.

Krause was born in 1760 in Bethabara, a frontier village settled in the 1750s in North Carolina’s Wachovia Tract by Moravian pioneers sent from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. He was orphaned by the age of two. In 1771, Salem’s master potter, Gottfried Aust, adopted him. Thus began a complex and often stormy relationship between two renowned citizens and craftsmen of the Wachovia settlement. Krause ran away from Aust in 1773 but became the potter’s apprentice in 1774. Ultimately, so many disputes arose between the two that the town council removed Krause from the Aust household and provided him room and board in the Single Brothers’ House (Fig. 6); from there Krause was escorted to and from his work at Aust’s pottery. Their problems continued to fester throughout the apprenticeship, which lasted until 1781.

On 20 March 1781, to help solve the chronic shortage of masons in Salem, Krause was released six months early from his apprenticeship at the pottery so he could learn the mason’s trade from Brother Melchior Rasp. Rasp, born in Salzburg, Austria, and trained as a stonemason in Frankfurt, brought an essential Old World skill when he arrived in 1755 as one of the earliest builders in Wachovia. When Rasp received Krause as an apprentice, however, he was 67 years old, blind in one eye and suffering from a variety of illnesses. In October 1782, after an eighteen-month apprenticeship, Krause was designated a journeyman working with the master, Rasp. On 19 March 1785, Rasp died, leaving Krause on his own with four years of training as a mason.

In 1783, Krause began operating the Salem brickyard to make bricks for the proposed Single Sisters’ House (Fig. 19), but after the Salem Tavern burned on 30 January 1784 the community council decided to use the bricks intended for the Single Sisters’ House to replace the tavern instead. The Moravian preference for using congregational members whenever possible for their construction projects limited their options when it came time to rebuild the tavern and although Krause had been trained as a stonemason, an agreement was negotiated for him to construct, as well as supply bricks, roofing tiles, and pavers for the Salem Tavern (1784) (Figure 21)—the first two-story, all-brick building in Salem.

Masonry work on the tavern commenced 16 June 1784 and was completed 11 December of that year. Its masonry details are particularly revealing, for in its construction Krause displayed his training as both a potter and a stonemason. His brick are oversized—measuring 12 inches long, 5-1/2 inches wide, and 3 inches high—and thus require two hands (rather than the usual single hand) to set in place. In this sense, Krause’s bricks function more as clay stones. Moreover, instead of using a single standard-sized brick and breaking some of them to form the closers required to even out a course of brick, Krause—the potter—molded different sized bricks to meet specific needs. Even a filler brick, a unit smaller than a queen closer, was individually molded. At the floor levels, instead of reducing the wall thickness by one brick course, as was normal practice for brickmasons, he used a smaller header brick to reduce the wall’s dimension. In these and other telling details, the tavern displays a craftsman working his way through a series of technical problems during construction.

Four days after the tavern was completed, the community council declared Krause a master mason. He was twenty-four years old. The following year, he completed the Gottlieb Shober House (1785) for a lawyer, entrepreneur, and later postmaster of Salem. The same year and across the street from Shober’s house, Krause constructed the long-awaited Single Sisters’ House (1786) (Fig. 19). He doubled the size of the 1769 Single Brothers’ House (Fig. 6) with a large 1786 addition to its southern end. In all of these projects, Krause employed the same construction detailing and the use of the oversized brick and other unusual techniques he first used at the tavern.

Krause was valuable to the community because of his unique technical skills, which evidently offset his frequently troubled relationships with the congregation. Problems included his purchase of a slave, horse trading, high prices for his work, and the brandy ration he gave his brickyard workers. A conflict between Krause and Gottlieb Shober during construction of the latter’s house even came to blows.

When the post-war building boom slowed in 1786, Krause planned to return to Bethabara and the pottery trade, but the council dissuaded him. He married Maria Meyer in 1786, bought a house, and soon took on various jobs including the position as road master, breaking stones for walls, and making smoking pipes of pottery. In 1787, he asked that the position of master mason be given over to Abraham Loesch, but by April of the following year the council noted, “concerning the bad mason work that is done at times it was suggested to have Gottlob [sic] Krause employed as the master mason.” Trouble with congregational rules, however, continued to mar Krause’s reputation. Finally, after unsubstantiated accusations of taking meat from the tavern smokehouse, Krause chose to leave Salem. In January 1789 he bought the Bethabara pottery, where he lived for the remainder of his life.

Krause’s importance in Salem’s architecture had just begun, however. By 12 September 1793, he was back in Salem to “take over the building of the new schoolhouse”—the Salem Boys’ School (1794) (Fig. 8) and to furnish the brick and roof tile for it. In this two-story brick structure, perhaps influenced by the “stranger” (non-Moravian) workman William Craig, Krause introduced into Salem decorative brickwork the pattern of Flemish bond brickwork with glazed headers that was manipulated to form lozenges, herringbone, and even letters. This was part of a surge of such expert brickwork in the western North Carolina Piedmont that blossomed in the last decades of the eighteenth century and the first few years of the nineteenth century. Such motifs were based in English, not German, craft traditions. Moreover in these decorated gables, as at the Boys’ School, Krause abandoned his oversized brick. Evidently in this project he had learned more than one new technique of the bricklaying trade, perhaps from Craig.

Krause’s next big project took the art of masonry a step further. In the brick Christoph Vogler House and Workshop (1797) (Figure 22), which he built for gunsmith Christopher Vogler, Krause relegated the oversized brick to interior walls, while for the exterior walls he employed a molded brick water table and elaborate use of glazed headers in a chevron pattern at the gable end plus initials worked into the brick walls—all expert brickmasonry techniques that contrasted with Krause’s earlier work. The “W” for Vogler on the front wall and his own “IGK” on the gable end (Figure 23) reflected the Germanic pronunciation and eighteenth-century script worked into the brick pattern—again, techniques based in English and mid-Atlantic traditions applied within a German community.

When the Salem community began construction of its large and elegant brick church, Home Moravian Church (1800) (Fig. 9), planned by the town’s administrator Frederic William Marshall, Krause started producing its roofing tiles in 1798. By 1799 he was both supervising and personally undertaking the masonry work. In the church, the masonry unit was standardized and the techniques were typical of a standard brickmason’s techniques; with Flemish bond brickwork, water table, and belt course. Little evidence remained of Kraus’s earlier techniques. In its scale Home Church was the largest building in Salem up to the 1830s.

Krause built two other large brick buildings in Salem. The Winkler Bakery (Figure 24), like Home Church, was begun in 1799. It reflects Krause’s full assimilation into the mainstream of nineteenth-century masonry and building design with a standardized brick and an increased attention to symmetry. The residence of the Salem physician, the Dr. Samuel Vierling House (1802) (Fig. 12), was the largest private house built in Salem at the time. It mimics the design set by the church in many details, most specifically the use of paint to simulate a more formal rubbed brick at the corners, window, and door jambs. (Some evidence exists that Krause may have also used paint on some of his earlier buildings.) In the gables, however, Krause retained the use of dark headers to form a series of chevrons. The house was completed in June 1802. By the following September, Krause had prepared his will and sold the pottery. He died the morning of 4 November, at the age of only forty-two, leaving a legacy of substantial, handsome, and uniquely crafted brick architecture that redefined the townscape of Salem.

Click here to read Johann Gottlob Krause’s entry in North Carolina Architects & Builders: A Biographical Dictionary.

Johann Heinrich Blum

Born: 19 April 1752

Died: 19 January 1824

Working: 1773–1824

Residences: Bethlehem, PA; Salem, NC

Johann Heinrich Blum was a mason working throughout the late 1700s and early 1800s in Salem. Blum was born in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania in 1752, although not much was documented of his childhood. He and his brother moved to Salem in the late 1760s.

It was in Salem that Blum began his training as a mason along with Johann Samuel Mau under the guidance of master mason Melchior Rasp. On 19 April 1773 Blum was released from his apprenticeship and given the title of journeyman.

The Salem elders considered Blum, along with Melchior Rasp, as an expert on the mason’s profession. It is mentioned in one episode that he and Rasp were asked for their ideas on different types of clay and specific uses. Blum is recorded as working on Salem’s Gemein Haus and a number of unnamed structures in the Moravian settlement of Bethabara.[8] Despite the respect he earned in Salem, Blum elected to “go out on his own.”[9] On 28 August 1775 Heinrich Blum left Salem for Pennsylvania, just two short weeks after the words and news of the Declaration of Independence had made their way to Salem.

While away from Salem, Blum served in the Continental Army aiding in the building of forts. His memoirs reflect on his abhorrence of killing and his thankfulness to never have to take part in such matters. Blum returned to Wachovia around 1788, his memoirs show he suffered from homesickness.[10]

In 1789 he picked up right where he left off as journeyman mason, however Blum’s limitations in brickwork seems to have left him out of favor in some instances to the more versatile Johann Gottlob Krause. This left him in need of money for his family, and Blum attempted several means to make ends meet. In 1790 Blum opened up a stone pit, and in 1791 was asked to man Salem’s kiln to burn tiles for roofs. He began full production of the town’s brick and roof tile needs in the autumn of 1791. By the summer of 1792, through brick making and bricklaying, Blum had paid his debts to the community. By 1794, however, Krause had taken over the brick making position within town.

Blum is recorded to have been working on the Ebert House and Salem’s Home Moravian Church (Fig. 9) between 1797 and 1800, laying stones for the structures. It should be noted that the town seems to have wished for Blum to take up the work of William Craig in order to settle local disputes about overcharging for services. Blum seems to have taken up these jobs without hesitation in order to provide for his family.

In 1800 Blum began work on plastering the Single Brothers’ House (Fig. 6).[11] It is here that is mentioned he worked for less than Johann Gottlob Krause. In 1805 payment records show his work in digging and walling the cellar of the Gottlob Schroeter House. In 1804 Blum worked on the Salem Girls’ Boarding School (Figure 25). There he walled up the rough stone, burned bricks, and pinned the wall plates. Blum was also responsible for laying the foundation for the shed and walling in the bake oven of the school.

Blum worked often with his sons, Abraham and John David Blum. Both of his sons may have carried on his legacy in masonry if not for their early deaths. After his work at the Girls’ School, Heinrich Blum seems to have concentrated his life on brick making and his plantation located outside of Salem proper. He died in 1824.

Heinrich Blum lived a more animated life than many of the inhabitants of Salem. He experienced war and peace, building and destruction. His life was never easy but he rose to the occasion wherever and whenever he was given the opportunity. Much of his work can still be seen standing today in Salem, a testament to this North Carolina builder.

Melchior Fischer

Born: 24 June 1726

Died: 1794

Working: 1774–1794

Residences: Heilbrunn, Wurtenberg, Germany; Lacaster, PA; Freidberg, NC

Fischer was a carpenter but also worked as a mason in Friedburg with his son George Fischer. See entry for Melchior Fischer under Carpenters).

George Fischer

Born: 2 June 1757

Died: 26 January 1832

Working: 1780–1810

Residences: Yorktown PA; Friedberg, NC

George Fischer sometimes worked as a mason with his father, Melchior Fischer, in Friedberg and Salem. He was primarily a joiner (see entry for George Fischer under JoinersJoiners).

Abraham Hauser

Born: 30 August 1761

Died: 27 December 1819

Working: 1782–1797

Residences: Frederick Co., MD; Salem, NC

Abraham Hauser moved with his family from Maryland to Salem sometime before 1782, when he was admitted to the congregation. He expressed a desire to learn a real trade, as opposed to the hunting and fishing lifestyle he had grown accustomed, and was approved to apprentice under Johann Gottlob Krause.[12]

Hauser often quarreled with individuals in the town and was caught spreading a rumor from time to time. This led to strife within the congregation about his conduct. In 1785 he built a farm and house outside of town.

In 1794 Hauser was appointed the roadmaster of Salem and was responsible for maintaining and building the roads, bridges, and fords in the area. He spearheaded a new bridge across Peters Creek in 1795.[13] Unfortunately he did not maintain the roads to the desired specifications and was removed from the position in December 1797.

After his failure as roadmaster, Hauser found it difficult to find work in Salem. His children moved to Indiana in the early 1800s—Hauser, however, remained in Salem until his death in 1819.

Abraham Loesch

Born: 22 August 1765

Died: 16 October 1843

Working: 1782–circa 1820

Residences: Bethlehem, PA; Salem, NC; Bethabara, NC; Bethania, NC

When Abraham Loesch was two years old his family moved from Bethabara to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.[14] Loesch attended school at Nazareth Hall in Bethlehem and then trained as a mason in Christiansbrunn, Pennsylvania.[15]

Sometime between 1782 and 1785 he moved with his family to Salem. In 1785 he aided in the building of Bethabara Moravian Church, as a mason.

Loesch had an interesting personal life that led to frequent conflict with the local leaders; however, his work was of such quality that he was named master mason at a young age at the behest of master mason Johann Gottlob Krause.

He is recorded in 1786 as beginning to perform mason work on Salem’s Single Sisters’ House (Fig. 19). He likely constructed the chimney on the side of the building, probably for the bake and dry-house.[16] Whether or not he completed the project is unknown because he was undecided about remaining in Salem as a mason.[17] Later that same year, however, he was identified as a mason in a list of Salem’s Single Brethren.[18] Around this time as well Loesch built the bake oven in the Gemein Haus in Salem (Fig. 17).[19]

In May 1787 Krause expressed his desire to name Loesch as master mason. This was done in part because Loesch wished for higher pay and also in part because Krause needed help on the many building projects underway in Salem at the time. Later that year, Loesch was consulted to raise the stone bridge to the Salem’s gun shop.[20]

In late 1787 or early 1788 Loesch was named roadmaster in Salem but he was not content with the position and his tenure was short lived.[21] [22] In 1788 he traveled back to Pennsylvania and learned the fulling trade. In 1789 he returned to Salem and constructed his own fulling mill and house.[23] He became a full-time fuller, holding the rights to indigo dye in Salem and only performed mason work on the side when time allowed.

In the summer of 1791 Loesch was hired to do the mason’s work on the Peters Creek bridge. He seemed adept at building bridges as there is a mention of his bridge being the only one across Muddy Creek that was accessible during flooding. By 1793 Loesch had built a house in Bethania where he also located his new fulling and saw mill.[24] Loesch was appointed in 1807 to oversee the construction of the Bethania Moravian Church. He also was placed in charge of hiring the workers who would construct this building. In 1815 and 1816 Loesch placed newspaper advertisements for platforms, water pumps, and piping as far away as Raleigh in the Raleigh Star and North Carolina State Gazette.[25] [26]

Abraham Loesch died in 1843 and his work can still be seen today in the Moravian churches in Bethabara and Bethania.

Click here to read Abraham Loesch’s entry in North Carolina Architects & Builders: A Biographical Dictionary.

Johann Michael Seiz Jr.

Born: 6 March 1765

Died: 17 May 1792

Working: 1784–1788

Residences: Broad Bay, ME; Bethania, NC

Johann Michael Seiz Jr. was born in Maine and moved to Bethabara in 1769 with his father along with about three hundred other Moravians who chose to relocate to Friedberg, North Carolina.[27] Seiz began to learn the linen weaving trade in 1782, but two year later he began another apprenticeship, under Christian Triebel, to learn the carpenter’s trade.[28] At some point between 1784 and 1785 he switched to masonry, learning under Johann Gottlob Krause. He completed this apprenticeship under Krause, along with fellow apprentice Abraham Hauser, and in 1785 was regarded as a journeyman mason.[29]

In 1786, Seiz, Krause, and Abraham Loesch, ventured out of Salem to make lime, a building commodity nearly always in short supply in eighteenth-century Salem. This enterprise seems to have been an attempt to supply lime for their work on the Single Sisters’ House (Fig. 19).[30] Seiz worked a few masonry jobs in Salem during 1787, including helping to lay stone for the Lick-Boner House and the Traugott Bagge House, but Krause, the master mason in town, received most of the project. Because of the lack of work for the journeyman masons in Salem—Seiz, Abraham Loesch, and Rudolf Strehle—in October 1787 the church adminstrators offered them the job of breaking and stacking rocks with permission to sell them to customers over the summer building season.

In April 1788 Seiz took over the old Hege plantation and married Catherine Hauser. The Aufseher Collegium mentions that he spent the rest of his days as a farmer.[31]

William Volk

Born: 27 June 1741

Died: unknown

Working: 1784–unknown

Residences: Pennsylvania; Salem, NC

William Volk was a mason in Salem, North Carolina. He was born in Pennsylvania. He worked alongside Johann Gottlob Krause on projects in 1784. He also worked with David Blum on the building of the home of the Boarding School inspector. However, he was not welcomed by the Salem Community proper due to conditions of character.

William Craig

Born: unknown

Died: unknown

Working: 1794–circa 1820

Residences: Salem, NC

William Craig, a brickmason who worked in Salem, was an “outside mason” or “stranger,” meaning not a Moravian, whose skills had a lasting impact on the brick architecture of the community. He worked closely with master mason Johann Gottlob Krause and may have introduced patterned brickwork into Salem. Although Craig was evidently highly skilled, he is an enigmatic figure: Nothing is known of Craig’s background, and, likely because he was not a Moravian, the church records give little information about him, his origins, or his family.

The first documentation of William Craig in Salem appeared on 24 April 1794 when the Aufeseher Collegium minutes noted, “we have heard that Gottlob Krause has accepted William Craig for mason work at the new school house construction… .”[32] According to the minutes, the acceptance of Craig as an apprentice or employee met with disapproval from the community and Krause was urged to reconsider. But on 6 May 1794 the minutes noted that the community grudgingly accepted his appointment.

The project that Craig was hired to assist in construction was the Salem Boys’ School (Fig. 8). The building displays Flemish bond brickwork with glazed headers that form decorative patterns, a distinctly different manner of laying brick from that employed in Salem previously (Figures 26 and 27). Craig may have shown Krause this new method based on his experience learned elsewhere. Such work was often seen in areas of Anglo settlement, such as New Jersey, but had not appeared in Salem before the Boys’ School construction. After its introduction in Salem, the use of glazed headers to form decorative patterns would become popular in the western Piedmont of North Carolina both English and German households.

Craig employed a more efficient way of laying brick than the method Krause had employed, which shared much more with the potter’s trade than a traditional bricklayer. Craig, like many brickmasons, also undertook work in whitewashing and plastering. He was recorded as whitewashing the rooms of Brother Frederic Marshall in 1795. A year later Craig was employed to plaster the house of “Sister Transou,” by prominent community member Christoph Vogler.

Craig’s most substantial project in Salem was construction of the residence for the church’s administrator, the 1797 Vorsteher’s House. He was given this task in its entirety, from laying the foundation to raising the roof. Town leaders found his work to be too costly and demanded lower pay for workers. Craig and the church administrators eventually came to an agreement and construction commenced. The Vorsteher’s House is a three-story brick structure set into the hill adjoining Main Street. It follows a central-hall plan, with detailing akin to its contemporary congregational buildings in Salem.

Craig was employed in 1798 to work on the foundations and “drawing up the walls” of Salem’s Home Moravian Church (Fig. 9).[33] [34] The mason’s work was noted as being particularly difficult as the slope of the building site was steep and the basement rooms, including the kitchen, required special attention to their construction. The task was cited as consuming more than 300,000 bricks with some of the work as high as thirty feet. Later in 1798, Craig fitted the stone plates for stairs, windows, door sills, and other tasks in completing the church.

Shortly after working on the Home Church, Craig left Salem. It seems that problems with the high wages he requested came to a head and he was asked to leave the community. The United States Census of 1820 lists a William Craig—possibly the same man—living with his family in Salisbury, North Carolina. Other than that census record, his whereabouts after leaving Salem are not known—nor is it known whether Craig was involved in any of the decorative brickwork on the various early federal-period brick houses and chimneys constructed in the western Piedmont of North Carolina.

Click here to read William Craig’s entry in the North Carolina Architects & Builders: A Biographical Dictionary.

John David Blum

Born: 21 March 1787

Died: 13 November 1860

Working: 1802–1842

Residences: Schöneck, PA; Salem, NC

David Blum was part of the second wave of construction in the congregation town of Salem that began in the nineteenth century. He was apprenticed to his father, Johann Heinrich Blum, where he learned the mason’s trade in 1803.[35] His father and he worked on several buildings together. In 1804 he aided in the construction of the Salem Girls’ Boarding School (Fig. 25). His father is documented as walling up the rough stone, burning bricks, and pinning the wall plates for the building. John David Blum was also responsible for laying the foundation for the shed and walling in the bake oven of the school. In 1805 he aided his father in the work of digging and walling the cellar of the Johann Gottlob Schroeter House on Main Street in Salem.

In 1805 Blum was apprenticed to Brother Christmann to learn the cooper’s trade.[36] Three years later, in 1808, he petitioned for the ownership of the plantation of Brother Opitz. His request was approved and he was given responsibility of running the plantation as well as making bricks in the summer months for use in construction of Salem’s buildings.[37]

Blum worked on the construction of the 1811 Inspector’s House, the residence for the headmaster of the Salem Girls’ Boarding School.[38] In 1823 he requested several acres of land on the Salem Tract to begin brick making in earnest, however this request was refused by the Aufseher Collegium as the land was deemed not suitable for such a purpose.[39] Two years later Blum was granted permission to build a schoolhouse near the northeast corner of the Salem Tract. Blum built a new house on their plantation in 1830, however his wife Sarah passed away before it was completed.[40]

Blum sold his plantation in 1842 and a few months later, in June 1843, he began building a home in the town of Salem.[41] The house was noted for its large size. He requested to open a store in Salem, but had his petition declined. Instead, John David Blum occupied himself as a mason in the surrounding area, finding work where it was available until a few years prior to his death in 1860.

William Hauser

Born: 1 July 1802

Died: unknown

Working: 1802–unknown

Residences: Bethania, NC; Salem, NC

William Hauser’s entrance into Salem came in February 1824 when Jacob Christmann hired him for a four-week project. His employment was accepted by the Aufseher Collegium under the condition his behavior be proper, hinting that his childhood had been rambunctious. His conduct was superior enough to earn him an apprenticeship under Christmann, and as a result Hauser was allowed to become a member of the Salem community.

In March 1828 Hauser left Salem to spend two years in Philadelphia learning the bricklaying and plastering trade.[42] He was allowed to keep his membership in the Salem congregation during this time as there was a noted shortage of masons in the community.[43] This was a rare honor because most individuals who left the town would be forced to reapply for membership upon their return to the community.

Hauser was forced to make a career decision in 1831 shortly after his return to Salem. Christmann was being dismissed from the congregation and as a result Salem was losing its only wheelwright. Under pressure from the Aufseher Collegium, Hauser had little choice but to open a wagon-building shop.[44] He built wagons only in the winter months while continuing his masons work during the warmer seasons. He continued this pattern for several years, serving as the only wheelright in town according to the records.[45]

In 1839, Hauser agreed to continue the wheelwright trade if allowed to build a house in Salem. This request was approved and Hauser was granted a plot of land at the corner of Main Street and Belews Creek Street. In 1841 he continued to expand on his grounds, building a two-story wheelwright shop.[46] Hauser proposed to build a new Salem house in 1845—whether or not this was allowed is not known. Four years later Hauser purchased a lot of land outside of the Salem town boundaries to sell lime and bricks. Lime had always been an item in short supply in Salem, with the nearest mines over thirty miles away, but demand had eased as the number of building projects in Salem declined. No further information is available for Hauser after 1858.

Pleasant Roberts

Born: unknown

Died: unknown

Working: ca. 1803

Residences: Bethania, NC; Salem, NC

Pleasant Roberts was a mason from Surry County, North Carolina who worked in Salem, North Carolina and was active around 1803. He was contracted as the master bricklayer for the construction of the Market-Fire House in Salem in late April 1803. At the same time Brother Stotz also contracted him as bricklayer for the Girls’ Boarding School (Fig. 25) in Salem.

Carpenters

Carpenters, along with masons, were the greatest contributors to the construction of the town of Salem. Using Germanic traditions, the carpenters were responsible for raising and forming the interior and the exterior of the homes. With hearty local timber of oak, tulip poplar, walnut, and pine, Salem’s carpenters had all the materials they needed for the massive construction projects in the town.

The Moravians used different terms for erecting log buildings (which they called Aufgeblockt) from raising a framed structure (Aufgeschlagen). The Moravian leaders viewed frame structures to be superior to log construction.[47] To erect substantial framed structures required the skills of a trained carpenter.

George Holder

Born: 27 January 1729

Died: 15 January 1804

Working: 1754–1768

Residences: Oley, PA; Bethabara, NC; Salem, NC

George Holder spent his formative years in Pennsylvania learning the carpenter’s trade. He moved to Bethabara on the 26 October 1754. In 1766 he was among the men who walked from Bethabara to the site of the town of Salem in preparation for construction. The other men were Niels Petersen, Jens Schmidt, Gottfried Praetzel, John Birkhead, Jacob Steiner, Melchior Rasp, and Michael Ziegler. Their directive was to “remain there for the time, in order to make a real beginning of building.”[48]

Their first project was construction of the Salem Builder’s House, begun on 6 January 1766. Together with Christian Triebel, the men laid most of the beams for the house. This building was a simple log cabin style home that served as the builder’s shelter through the end of the winter and into the summer.[49] The men were in favor of building a real house, not a temporary structure.[50] As such, the house was built 26 feet by 22 feet with a tile roof and made weather tight.[51] This structure remained standing until around 1907.

Holder also had a hand in felling the trees and preparing the lumber for the Outsider’s Cabin on the same lot as the Salem Builder’s House.[52] This house was to be occupied by all the hired workmen who did not belong to the Moravian congregation. He aided in the completion of the First House, in which he lived for a time, and served as the bush-ranger in order to find roads and paths that led to Salem. He mapped these routes to aid in expediting travel between the Moravian settlements of the Wachovia Tract.[53]

Near the end of 1766 Holder made the clapboards for the horse stables in Salem. Two years later, after being appointed overseer of roads, he was hired to chop out the roads to Town Fork and Belews Creek. These roads are documented as being supposed to be good enough for riding.[54] After serving as bush-ranger, Holder was granted a tract of land by the town council to have a farm. He finished his days as a farmer, practicing joinery here and there, and was responsible for the completion of many of the buildings on his land. He died 15 January 1804 in Bethabara.

Jacob Steiner

Born: 1734

Died: 1801

Working: 1755–1777

Residences: Warwick Township, Lancaster, England; Bethabara, NC; Salem, NC

Jacob Steiner arrived in Wachovia on 13 June 1755. The Wachovia Diary says that Steiner came to the new town (Salem) with seven other brethren, Niels Petersen, Jens Schmidt, Gottfried Praetzel, John Birthed, George Holder, Melchior Rasp, and Michael Ziegler. Here he aided in the carpentry on the 1766 Salem Builder’s House and later that year he helped Christian Triebel with some of his carpentry projects.

In 1773, worked on construction of a mill that he owned in partnership with the Moravian Church (Wachovia Diacony).[55] He also built the Miller’s House in order to house himself, his wife, and those helping to build the mill. This mill was built just outside the boundaries of Salem, as Steiner was not considered a resident of the new town. He owned a 1/3 stake in the mill while the church held the rest.[56]

Steiner also assisted in construction of the Salem Saw Mill in 1777. Here he invested time and capital into the building in order to become a partner in the enterprise. The Aufseher Collegium recorded, however, that he did not want to own the enterprise entirely. After working as a carpenter on Salem’s first buildings, Steiner returned to the milling, the trade he would practice for the remainder of his life.

Christian Triebel

Born: 6 November 1714

Died: 16 April 1798

Working: 1755–1788

Residences: Henneberg, Thuringia, Germany; Bethlehem, PA; Bethabara, NC; Salem, NC

Christian Triebel was a master carpenter who, like the mason Melchior Rasp, brought his Old World skills to the Wachovia Moravian settlement in North Carolina and helped construct buildings in Salem and elsewhere that represent the state’s sole surviving examples of European building traditions transferred directly to colonial North Carolina. Among his best-known surviving works is the massive, half-timbered Single Brothers’ House (Fig. 6) in Salem, which exhibits Treibel’s skills in traditional heavy framing that defined Salem’s early architecture.

Little is known of Triebel’s early life, except that in his memoir he recalled his younger days as something of a hooligan in Henneberg, Germany before he affiliated with the Moravians and converted to a pious life. He left Europe in November 1754 and spent a brief period in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. He arrived in Bethabara from Bethlehem on 11 October 1755, just two years after the pioneering group of Moravians began the community in 1753. In early November 1755, Triebel was joined in Bethabara by the mason Melchior Rasp, and they and other men kept busy constructing buildings in Bethabara.

After the site was selected for the new principal town of Salem in 1765, Triebel, at age fifty-one, faced what must have been the greatest building challenge of his life: the construction of a new town in the wilderness with substantial and well-crafted buildings erected using traditional techniques. In January 1766 Triebel was a member of the first crew of workmen sent from Bethabara to Salem to construct a temporary log house for the workmen. By March of that year he was busy selecting timber for the first permanent buildings in Salem, and on April 22 Triebel and his apprentice Rudolf Strehle went to Salem and “began work on the framing for the first house to be built.” Salem’s Community Store (Figure 28) owner Traugott Bagge said of Triebel in November 1766:

Br. Triebel is surely a faithful brother on his part, and although he often has much to object to and expresses himself somewhat roughly, it must be said that he has worked very hard at his trade, made harder because he has always been alone and that is just now for us and for him the most difficult thing in Salem. Otherwise I regard him as one of the most faithful in the Choir.

Triebel’s skills were essential to construction of Salem’s half-timbered buildings, which employed traditional techniques he learned in Europe. Raising the heavy structures was sometimes dangerous, especially for the larger structures. On 8 January 1766, while Triebel and other men were erecting the Salem Builders’ House, “Br. Triebel, chief carpenter, fell from top of wall while helping place the roof timbers, not hurt.”[57] In 1769, while “raising the Single Brothers house in Salem, a piece of timber fell, taking with it a wall which was not yet secured; it might have swept a number of Brethren from the second story to the ground, or have crushed others as it fell, but the angels guarded them and no one was hurt.”[58] In October 1779, Triebel broke his leg in a fall while working on the Bethabara mill; this injury plagued him for the rest of his life.

By 1769, with seven dwellings, a workmen’s house, tannery, and the large Single Brothers’ House constructed, Salem’s administrator Frederick William Marshall began consulting with Triebel and Melchior Rasp on construction of the town’s principal congregational building, the Gemein Haus, to serve for worship, community meetings, and other purposes. Rasp constructed the first story of stone and Triebel framed up the second story in the half-timbered method used for the previous buildings. The Gemein Haus was completed in 1771 and in 1772 Salem was deemed ready to accept the Moravians who were assigned to move from Bethabara to practice their trades in the new town. In 1774 Triebel built a house at his own expense on Lot 59 in Salem (at the corner of present Academy Street and Main Street). This structure was approved by the Congregational Council on the condition that Treibel would house the night watchmen in an upstairs room, which he did for several years.

For some projects, such as a bridge over Muddy Creek, the congregational leaders contracted with outsiders after consultation with their master carpenter Christian Triebel. But in 1775, while planning construction of the waterworks, which involved a system of wooden pipes to deliver water to Salem, “it was not approved to give the contract to an outsider and Triebel, Krause and Frederick Beck said they would do the work for the price named.” The contract drawn up with Triebel in 1776 stipulated, “to square the wood, we keep the old price i.e. per 100 ft. 12 sh. [shillings]. As to the other carpenter work we shall make a special contract with him.” In December 1777 Triebel, Johann Gottlob Krause, and another man stated that they were “willing to undertake the bringing of water pipes to the town… Br. Triebel has agreed to cut and bore the pipes according to directions and a contract will be made with him per yard.” It was agreed that he should have “4d. Congress money for each log he cuts for pipe and 3.5d. of old money for each foot bored.” (The difference in the money referred to the financial situation during the American Revolution.)

In early January 1778 Triebel was cutting trees for the waterworks project, which at age sixty-four must have been demanding work even with the help of his apprentices and other men. By mid-month, he asked the governing board for a dollar more per log than agreed upon (possibly reflecting wartime inflation). The adjustment was made, and by February he was boring pipe again. But the American Revolution, other construction work, and an accident at the Bethabara sawmill slowed his progress on the waterworks.

During the war years, Triebel busied himself making gutters for the Gemein Haus and the store. He also supplemented his income by selling gravestones and making well pumps. During the war, troops were housed in his home, and later part of it was rented to the Salem Boys’ School (Fig. 8). Also, in 1780 Triebel entered a contentious period when another man wanted to buy his wood-boring equipment and replace him at pipe making. Triebel refused and continued making the pipes until the mid-1780s. Triebel also worked as a gravestone cutter, and although this task was seldom mentioned in his records, it is noted that he fashioned and sold stone markers—which in the Moravian tradition were simple square or rectangle markers inscribed with only the name and lifespan of the deceased.

As the postwar building boom accelerated, Salem again required the master carpenter’s construction skills. In February 1784, Frederick William Marshall lamented that the community was “handicapped by the lack of workmen.” “Our master carpenter Triebel, is in his seventieth year,” Marshall wrote, and Triebel was being treated alongside master mason Melchior Rasp “in the sick room.” Triebel evidently recovered sufficiently to serve Salem for a few more years. The congregation called on him to assist in completion of the new, brick Salem Tavern (1784) (Fig. 21), for which Johann Gottlob Krause was the brickmason. For the 1786 Single Sisters’ House (Fig. 19), another large brick building, it was decided “to keep Triebel for the frame work of the Sisters House because we are doubtful to leave this to Strehle [Triebel’s former apprentice] by himself.” Triebel responded that he was “willing to help with the construction as much as possible for 4 sh. [shillings] a day.” This was the last project in which Triebel was mentioned; with his health failing and his old leg injury troubling him, he was no longer able to work, and his memoir states that he was forced to give up his trade about 1786 or 1788. He had employed his skills to make an entire town rise in the wilderness, and his surviving works represent some of the principal examples of first-generation German immigrant architecture from colonial America.

Click here to read Christian Triebel’s entry in North Carolina Architects & Builders: A Biographical Dictionary.

Rudolf Strehle

Born: circa 1751

Died: unknown

Working: 1764–1790

Residences: Bethlehem, PA; Bethabara, NC; Salem, NC

Rudolf Strehle was born around 1751 and arrived in Bethabara on 1 November 1764 with his family. He is first listed as a carpenter in the “Boys and Prentices” section of the list of inhabitants of Bethabara in Wachovia.[59] He is identified in November of that year as apprenticing with Christian Triebel.[60] He commuted from Bethabara to Salem while working with Brother Triebel on the first buildings of Salem. He then moved permanently to Salem in 1772.

Strehle worked with Triebel closely for years. He is recorded with Triebel constructing the Salem Gemein Haus shingles in 1777 and a year later cutting logs suitable for water pipes for use in and around Salem. He is listed working on a building with fellow carpenter Martin Lick in February 1781.[61] A week later Strehle was asked to fill the night watchman position, which he accepted and filled for several months. Near the end of 1781 he was sent to Bethabara to help the American military forces of General Pickens, likely to aid in the wooden fortifications of the area.

In 1785 Strehle worked on the frame work of the Single Sisters’ House (Fig. 19) with Christian Triebel.[62] In October 1785 he, along with Martin Lick, built an addition to the Single Brother’s House so that they could continue their carpenter and joiner work in foul weather.[63] Strehle and Lick were both caught accepting work outside of Salem without notifying the congregation, an act that was not viewed favorably by the church administration. Both men were criticized for seeking too much money for their work based on this decision.[64]

In 1786 he, along with Lick made the guttering for the Gemein Haus in Salem. He is later listed as breaking stones with Brothers Abraham Loesch and Johann Michael Seiz Jr. for the summer building season.[65] 1789 saw Strehle working on several pumps for various inhabitants of Salem. He worked on the pump at the home of Brother Herbst as well as the Single Sisters’ House. In the spring of 1790, Strehle moved to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, in search of more steady work than he was able to find in Salem.

Niels Petersen

Born: 3 April 1717

Died: 4 November 1804

Working: 1766–1774

Residences: Oddes Brandrop, Danish Holstein; Bethabara, NC; Salem, NC

Niels Petersen was born in what is now Denmark in a town that bordered today’s Germany, where he was introduced to the Moravians. He arrived in Bethabara from Charleston, South Carolina, on 30 January 1766. He was sent to North Carolina to serve as Bethabara’s first distiller but before he could produce any spirits he first worked to build the town of Salem.

Petersen aided in the building of the Salem Builder’s House and then went to work planning and building the town’s distillery. It was as Salem’s distiller, not Bethabara’s, that he practiced his craft for most of his life. Petersen’s work ethic was well recognized in town and in 1774 he was appointed to the committee to construct the waterworks of Salem. This was one of the most important projects in the town and also one of the first water programs undertaken in the American colonies.

Petersen also seems to have had skills for resolving conflicts. He mediated a dispute between Johann Gottlob Krause and Gottfried Aust that resulted in Krause returning to his foster father to learn the potters trade. Without Petersen’s intervention, the career of one of Salem’s most prolific and influential brick masons may never have been realized.

David Holzapfel

Born: circa 1750

Died: February 19, 1856

Working: circa 1770–1856

Residences: Broad Bay, ME; Friedland, NC

David Holzapfel came with his wife to the Lutheran colony of Broad Bay, Maine in 1742. This was a Lutheran settlement established by General Samuel Waldo. Two years prior to Holzapfel’s arrival, the colony had suffered a devastating attack by Native Americans allied with the French during King George’s War.

Holzapfel was a carpenter by trade, and built the first frame house in Broad Bay. There they lived until 1772 or 1773, when the couple along with around three hundred others moved to Friedland, North Carolina. He built his own frame house in Friedland, another frame house. Holzapfel was familiar with the Moravian Church but was not considered a member.

When the American Revolution came about, Holzapfel joined the fight, likely emboldened by the war stories from Broad Bay during his younger years. Holzapfel was a part of Washington’s Continental Army. He used his carpentry skills to repair and improve the fortifications of Fort Ticonderoga. He suffered through Valley Forge and crossed the Delaware with Washington during the attack on Trenton.

Holzapfel returned from the war and engaged in putting his carpentry skills to constructing buildings in the surrounding community on into the nineteenth century. Not much is recorded about his later life, Holzapfel died at the age of 106 on 19 February 1856.

Melchior Fischer

Born: 24 June 1726

Died: 1794

Working: 1774–1794

Residences: Heilbrunn, Wurtenberg, Germany; Lacaster, PA; Freidberg, NC

Melchior Fischer trained in carpentry in Germany and came to America in 1750. He settled in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he served as a master carpenter for three years. Fischer was among the group of original builders in the Wachovia Tract who brought the artfulness of the Old World style to the New World.

Fischer moved to North Carolina in 1774. He and his family settled in Freidberg. His son George Fischer worked as a joiner in Friedberg and Salem.

Martin Lick

Born: 11 November 1759

Died: 4 January 1834

Worked: ca. 1777–1789

Residences: Bethabara, NC; Salem, NC

Born in Bethabara in 1759, nothing else is known of Martin Lick’s childhood until he moved to Salem in 1772 and entered the Single Brothers’ House to learn the trade of a joiner.[66] After serving a joinery apprenticeship for several years, Lick decided to pursue the carpenter’s trade. He was allowed by the church adminstration to do this if he agreed to make the window frames for the Single Sisters’ House (Fig. 19) under master cabinetmaker Johann Krause.[67] At the time, however, Krause did not wish to take an apprentice and Christian Triebel was consulted on the matter. Triebel was too old, so Lick was apprenticed instead to Frederick Beck, a master joiner.[68]

However, sometime between 1775 and 1780 Krause consented to taking Lick as his apprentice in carpentry. Lick worked as Krause’s apprentice until 21 November 1780 when the two men went through the customary ritual of exchanging indenture papers, a show of an apprentice’s freedom from their master.[69]

In February 1781, Lick and Rudolf Strehle were sent to help the Brethren in Bethabara, where General Pickens’s American forces were stationed. They were likely working on the wooden fortifications near the town as well as providing general support to the Continental Army.

Lick made several attempts at increasing the amount of carpentry and joinery work he received in Salem. He often partnered with Rudolph Strehle, another woodworker, who was released from his apprenticeship around the same time as Lick. The men attempted to establish their own space around the Single Brothers’ House (Fig. 6), and were successful in building an outdoor workshed.[70]

An interesting note in Lick’s records was his request, along with others by carpenters in Salem, to be compensated for the cost of his tools. The town’s administrators determined that the carpenters would not be compensated for their hatchets, axes, adzes, hand saws, and squares. Any other tool needed for specialty work, that typically only a master could afford, would be paid for in part by the community.[71] Lick was often in trouble for taking work outside of the community for rates higher than those approved by Salem. Lick was frequently financially strapped throughout his life and seeking work outside of Salem was his attempt to build a name for himself and his business.[72] Lick was listed as a cabinetmaker and carpenter among Salem’s Single Brothers, reflecting that he maintained his good status among the Moravians in order to give him the most options for his carpentry work.

In August 1786 Lick and Strehle were given the task of making the roof spouts for the Salem Gemein Haus.[73] In December of the same year he was tasked with adjusting the roof elevation of his own home, which prompted him to request the right to build a house in Salem. He built what is now known as the Lick-Boner House as his personal residence.[74] Lick’s house was originally a log structure with a central chimney. Below there was one room at the north end that also served as the entrance. On the south end there were two rooms and above was a loft. The same floor plan has been found in one other house in Salem: the Chimney House, built in 1789 by Abraham Loesch. While following the same plan as Lick’s house, the Chimney House was built on a larger scale. The chimney girth construction—possibly unique to these two old houses in Salem—spanned the length of the house and is supported in the middle by the chimney.