In 1836 Rev. W. R. Thomason of the Pulaski Female Academy in Giles County, Tennessee stated that the goal of female education was “to preserve and cultivate the ornamental character of the female sex.”[1] During the years of Tennessee’s settlement and early statehood, public education was non-existent. In the early nineteenth century, the first small, private schools were established by clergymen or individual proprietors, or subscription schools were created in which a consortium of parents hired a teacher. Some children had private tutors. Students only went to school if their parents could afford it, and male education took priority. Nashville had public schools by 1852 and Memphis followed suit in 1858; however, it was not until after the Civil War that a state-wide, public school system was established.[2]

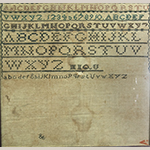

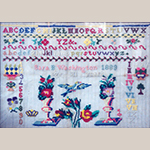

Children aged two to six who were not educated at home might attend dame schools, called infant schools in Tennessee, which met in the teacher’s home or a public building (Figure 1).[3] The coed schools were a combination of day care, nursery schools, and kindergarten, although in Tennessee some served as grammar schools as well. Students learned the rudiments of reading, writing, arithmetic, sewing, and knitting. Young girls often made their first needlework samplers at an infant school.[4] The first sampler was a marking sampler with letters and numbers (Figure 2).[5] [6] Teachers taught needlework by demonstration and example. The techniques used in cross stitch required patience, tenacity, and manual dexterity. Hence the best way to learn the stitches was to execute a sampler.[7]

One of the earliest infant schools in Nashville was opened by Mrs. Eleanor Clopton on 14 March 1804.[8] For many girls an infant school was the only education they would receive. Judith Long ran a dame school in Williamson County from 1832 to 1837 where she taught ornamental needlework in addition to the basic curriculum.[9]

After leaving an infant school some girls might go on to a subscription school or a preparatory school, then on to a female academy, if their parents approved of higher education for women.[10] Subscription schools were usually coed, but academies were segregated by gender on separate floors or in separate buildings. An academy was a high school, but some academies had preparatory and collegiate departments as well.[11] Most girls either graduated or left an academy at age sixteen. It usually took ten years for a girl to receive a complete education.

There were three basic types of female academies in the nineteenth century: 1) schools that were proprietor/principal operated; 2) chartered schools with stockholders run by trustees, and 3) church affiliated academies.[12] Tennessee also had schools founded by societies such as the Masons, the Odd Fellows, and the King’s Daughters. The liberal arts curriculum at female academies was similar to that of the male academies with the addition of ornamental subjects such as embroidery, drawing, painting, and music. Female boarding schools in the South were modeled on English ones, which catered to aristocrats and the gentry, and southern plantation owners and prosperous businessmen sent their daughters to boarding schools to complete their educations and learn deportment and elocution.

Prior to the 1830s, most wealthy Tennessee girls traveled north to be finished as there were few academies for them in the South.[13] The Salem Female Academy in Salem, North Carolina was an exception. From 1805 to 1905 nearly five hundred students traveled to Salem from Tennessee.[14] The first Tennessee girl to attend Salem—after the school opened its doors in 1805 to girls who were not members of the Moravian faith—was Laetitia Saunders, daughter of James Saunders of Sumner County in Middle Tennessee.[15] While school records reveal that Laetitia purchased embroidery silk at Salem, her needlework has yet to surface.[16] In 1817 sisters Susannah Childress and Sarah Childress from Murfreesboro, Rutherford County traveled to Salem by horseback—a journey that took a month—and enrolled in the academy.[17] Sarah Childress, the future wife of United States President James K. Polk, created a mourning embroidery at the school that she treasured her entire life (Figure 3).[18]

Overcrowding at the Salem Female Academy became an issue in 1813 when ninety girls were enrolled at the boarding school. The Clarion and Tennessee State Gazette in Nashville published an advertisement in 1814 announcing that parents who wished their daughters to attend the Salem Female Academy would have to put their name on an eight-month-long waiting list. During the Civil War, twenty-nine students came from Tennessee as parents thought they would be safer at Salem.[19]

The first female academy in Tennessee was Fisk’s Female Academy located in Hilham, Overton County, founded by Moses Fisk in 1806.[20] In Nashville, Mrs. Tarpley’s Female Seminary advertised in 1810 that “…young ladies will be taught Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, English grammar, Sample work, needle work, embroidery, drawing, Painting, and Filigree.”[21] Mrs. Tarpley’s school was not as rigorous as the Salem Female Academy, however, which precipitated the founding of the Nashville Female Academy in 1816 (Figure 4).[22] The academy was chartered by a group of business men who preferred to have their daughters educated closer to home.

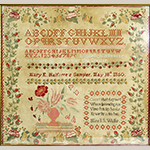

By 1825 several female academies had been chartered in Tennessee. In addition to previously mentioned schools, in 1825 the Soules Female Academy was established in Rutherford County and in 1827 the Knoxville Female Academy.[23] Williamson County had the Female Academy founded by Rev. and Mrs. Johnathan Blackburn in 1822 and the Harpeth Female Academy (also known as the Harpeth Union Academy) was begun in 1828.[24] More schools were founded in the 1830s as citizens became aware of the important role mothers had in raising the future leaders of the country. Between 1827 and 1839, twenty-eight female academies were chartered in twenty-five Tennessee counties. Many of these schools still included the ornamental arts, but they were relegated to an extra-curricular status—available but for a separate fee (Figure 5). By 1860 Williamson County had founded twenty-three female schools, the most of any county in the state.[25]

Many female academies began in homes while others were built to look like houses to create a welcoming atmosphere for boarders. Still other academies moved from houses to larger campuses with multiple buildings (Figure 6). In the 1830s the Talliaferro sisters, Harriet and Henrietta, founded the Pleasant Grove Female Academy in their father’s residence in Williamson County.[26] In 1829 the Knoxville Female Academy, which later became the East Tennessee Female Institute (Figure 7), opened in a building that resembled a home but was in fact built with the sole intent to operate as a school.

Rev. Franklin G. Smith of the Columbia Female Institute (Figure 8) believed that the female intellect was equal to that of the male, including for calculus and physics.[27] In 1841 the curriculum of the institute’s Junior Department included orthography (spelling), orthoepy (pronunciation) and definitions; reading, writing, and English grammar; geography with maps and globes; arithmetic; American history; Jewish, Grecian and Roman antiquities; an introduction to ancient history; rhetoric; and mental philosophy. For an extra fee a young lady could take Greek, Latin, French, Italian, or Spanish. She could also study piano, organ, guitar, or harp as well as drawing and painting, riding, daily exercising, and fancy work of every description, which included embroidery, crochet, shell work and feather work. The Senior Department at the Columbia Female Institute expanded on those subjects by adding algebra and geometry; political, moral, and mental philosophy; and penmanship. Good penmanship was considered a necessary skill as letter writing was an essential form of communication. Tuition in the Junior Department was $20.00 for a semester and $25.00 in the Senior Department. Foreign language lessons cost an additional $10.00 per semester; harp lessons $30.00; organ, piano, and guitar lessons $25.00; drawing and painting $10.00; and fancy work $10.00.[28] This fee schedule was common at most female academies, and as a consequence it was often more expensive to educate a female than a male.

Once the middle class began to prosper in the late 1820s to early 1830s, the daughters of professionals, merchants, and moderately well-to-do craftsmen and farmers could afford to send their daughters to an academy. Not all of those girls lived on plantations or in manor houses—some lived in log homes—yet all of the girls had parents who wanted a genteel education for their daughters.

In order to attract a good husband and enter polite society a girl had to have a refined education.[29] Above all, they had to be ladylike and skilled at conversation. Some schools held chaperoned salons in school parlors for young ladies to practice their manners and to learn the art of conversation.[30] Girls were also taught to quote poetry, speak a foreign language—especially French—and study the ornamental arts. The ornamental arts included drawing, painting, and music, as well as fancy work. The Columbia Female Academy taught lace work. The Spring Hill Female Academy advertised that “A young Lady qualified to teach Painting and Wax Work will attend in the Academy on reasonable terms.”[31] Girls also practiced hair work, especially in the 1850s when hair jewelry was popular. Such skills were taught to help students decorate their future homes. Although girls mastered deportment and the art of conversation as well as the ornamental arts, there is no evidence that they were taught to cook. Franklin G. Smith, of the Columbia Female Institute and later the Athenaeum, stated that a certain “Madam S.” used to say that “she educated her young ladies for the Drawing room not for the Kitchen.”[32]

Many girls took drawing and painting lessons in lieu of needlework or in addition to it. Some painted freestyle while others painted theorems using stencils on velvet or paper. One such theorem, made by Mary H. Henly in 1848, was likely done at the Jonesborough Female Academy in Washington County (Figure 9).[33] In 1830 Ann P. Bridges was attending the Mr. and Mrs. Hunt’s Female Academy—which was later absorbed by the Gallatin Female Academy—where she made two small theorems (Figure 10) with the intent of making a reticule.[34] Caroline Walton Allen created a watercolor of a rose at the Nashville Female Academy in 1824 (Figure 11).[35]

Music, both vocal and instrumental, was by far the most popular ornamental art taught in female academies. It was essential to a refined education, as it prepared young ladies to entertain in their homes. Music was included in almost every school curriculum whether or not other ornamental courses were offered. The larger academies employed a number of music teachers who taught different instruments. In 1859 the Nashville Female Academy advertised that the school had an “ample supply of teachers for Piano, Harp, Guitar, and Vocal Music”—not only enough for the students, but for “those Ladies in the city who may wish to take lessons.”[36] Students who attended the academy for music only were called Parlor Boarders. The Athenaeum advertised in 1861 that they had three teachers for the piano and one for the guitar and singing. Yet the academy only employed one teacher for fancy work and dancing.[37] Tuition for an instrumental class could easily cost more than regular tuition as it included rent for an instrument. At the Odd Fellows Female College in Rogersville, regular tuition varied from $20.00 to $35.00 with $40.00 additional for music.[38]

Knox County parents felt so strongly about training girls in the ornamental arts that they dismissed the first principal of the Knoxville Female Academy because of his “lack of interest in the ornamental branches of study.”[39] After the new principal was hired, a separate building was constructed to house the ornamental branches. Conversely, the Trustees of the Nashville Female Academy prohibited dance lessons; however, when some parents wished their daughters to learn to dance, administrators permitted girls to receive their lessons off campus. In 1844 a problem arose which caused quite a fracas. Rev. Dr. Collins D. Elliott, the Nashville Female Academy principal, allowed students to have dancing lessons in the boarding house which he felt was easier and safer than traveling off-campus. It so infuriated the Trustees that Elliott temporarily had to resign from the Methodist Church.[40] A sampler done by Martha Ann Lytle, probably while attending the Nashville Female Academy in 1834, is illustrated in Figure 12.[41]

The Cult of Domesticity which began in the nineteenth century was based on the belief that the home should be a haven with the mother as the center of moral and Christian authority.[42] Rev. Dr. Elliot of the Nashville Female Academy, which was non-sectarian, wrote that one of the goals of the academy was to “educate the girl according to God’s Word and the demand of every fiber of her mind to be a wife, to be a mother. Then in after life, circumstances determining, she may do anything a female body, mind, and soul may do.”[43] Training in obedience and piety would enable young ladies “to beautify and bless their future homes.”[44]

Prior to the 1850s, teachers in Tennessee came from Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, or northern states where they were trained to teach. Mrs. Louisa E. Walker Parkes, a former student at the Franklin Female Institute, said that “hiring teachers from the North was the ‘in thing’ to do in those days.”[45] Franklin G. Smith, who founded the Columbia Athenaeum, was from Vermont and educated at Princeton in New Jersey. His wife came from Lynchburg, Virginia. The Nashville Female Academy’s head, Rev. Dr. Elliot, was from Ohio. Mrs. and Mrs. Blackington at the Franklin Female Academy hailed from Massachusetts. Many tutors and governesses also traveled from the North. The teaching profession was not well paid. Teachers often boarded with families in the area. The faculty of the Nashville Female Academy employed teachers from Germany, England, and France as well as the North. At first northern teachers were accepted in southern schools, but as the divisiveness over slavery grew, the cultural and class differences caused alienation. By the 1850s, most southern administrators and parents wanted only southern teachers.

Teachers who were recent graduates were only slightly older than some of their students. Thus, girls who boarded and students with governesses often developed close relationships with their female teachers. Isabella Wallis, who taught at the Union Academy in Williamson County, formed a close relationship with her student Mary Halfacre. In 1850 Mary Halfacre stitched Miss Wallis’s name into her sampler (Figure 13).[46] And in 1851, her teacher stitched a perforated paper embroidery as a gift for Mary (Figure 14).[47] Elizabeth Jane Armstrong of Knoxville corresponded with her governess Lemira Watts Yarnell for years after her schooling was over (Figures 15 and 16).[48] Eliza H. Yarnell, Lemira’s sister, was also a teacher. Eliza taught Telitha Ann Hill to stitch in Anderson County (Figure 17).[49]

A number of girls’ schools in Tennessee were founded by ministers and their wives. Rev. and Mrs. Henry Hunt had a female academy in the 1830s in Gallatin, Sumner County, which taught both plain and ornamental needlework at no extra charge (Figure 18).[50] Rev. Tolbert Fanning and his wife Charlotte Fall Fanning opened in succession the Fanning Girls School, which became the Franklin Female Institute in Franklin, Williamson County, as well as Franklin College (Figure 19) and another incarnation of the Fanning Girls School in Nashville, Davidson County.[51]

Some teachers moved from school to school looking for new opportunities, while others initiated new schools. Mr. and Mrs. Ellis were living in Sumner County in 1819.[52] In 1833 they operated the Marble Hill Female Academy in Antioch, Davidson County, where Mrs. Ellis taught needlework to Ellen Mordaunt Oldham (Figure 20) and to Caroline Frances DeMoss (Figure 21).[53] Ellen honored Mrs. Ellis on her 1833 sampler in her signature band (Fig. 20). In 1834 the Ellises were teaching at the Porter Female Academy in Triune, Williamson County. By 1837 Mr. and Mrs. Ellis were in charge of the Mt. Vernon Female Academy at Hardeman’s Crossroads in eastern Williamson County. Then in 1839 they were in Maury County, in charge of the Spring Hill Female Academy.

There were mothers and daughters and sisters who taught. Catherine Barr Wallis, who taught Lamyra Jane Liggett to stitch in 1850 (Figure 22), was the sister of Isabella Wallis, the woman who taught Mary Halfacre at the Union Academy in Williamson County.[54] The Wallis sisters may have learned needlework from their mother, Polly Hargey Wallis, who was likely the daughter of John Hargey, the founder of a female academy in Lexington, Kentucky in 1790.

A typical academy had two semesters composed of four-and-a-half or five-and-a-half months each. Most schools had a Fall Session from August to mid-January and a Summer Session from February to mid-July. Students rarely had time off for Christmas, but they did have special meals and festivities to celebrate the holiday. Public examinations and closing exercises were held in June or July, followed by a vacation of a month or two.[55] At the Columbia Athenaeum each session culminated in three days of oral and written examinations and a concert of vocal and instrumental music. Needlework and art were exhibited for all to see. These examinations were widely attended by the families and members of the community, some of whom viewed it as entertainment. Hence, it is not difficult to imagine the fear and trepidation that young girls must have experienced when they were examined in front of a large audience. The girls studied diligently to avoid dishonoring their families. It was so frightening for some of them that they chose not to graduate.[56] As a result, some academies later dispensed with public examinations and held graduation and award ceremonies instead.

The school day often began at sunrise and ended as late as nine at night. In schools that had a religious affiliation, the day started with chapel. The classes where held for two hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon, with walks after breakfast or in the late afternoon. The main meal was served at midday. The remainder of the day was spent studying, sewing, practicing music, letter writing, and eating. Girls who were taught embroidery were assigned periods to do their stitching. In other words, they had to methodically complete a certain amount of work on their sampler each day in order to finish it by the end of the school term.

Parents who chose to send their daughters away to boarding schools were justifiably concerned about their health, maternal care, and moral supervision.[57] Boarding accommodations varied. In the smaller schools, students lived in private homes or stayed with relatives. To ease homesickness, boarders often came to school with friends or relatives. Larger schools offered dormitories. The dormitories at the Nashville Female Academy featured steam heat, gas lighting, and bathtubs with hot and cold running water.[58] Girls had to get their parents’ permission to use the bathtubs, however, because it was feared that “vapory young ladies might go into decline as a result of it.”[59] Of the 432 pupils who attended the Nashville Female Academy in 1859, 225 were boarders.[60] The school promoted a healthy, nurturing atmosphere, advertising in 1855 that “Cholera, Chills and Fever, Typhoid and Scarlet Fever, and similar fatal disease, have never occurred here. But three deaths of Boarders in thirty nine years.”[61]

The rules for boarders and day students at the Nashville Female Academy stipulated that “…young ladies see no company; never visit but with our approbation; read no novels; never leave the yard but in company with a Teacher.” Novels were thought to be too excitable for young constitutions; however, the ban may have just made the books more tantalizing to students. In later years no Nashville Female Academy student was “permitted to associate with any other school girls, who attend promiscuous dancing schools, parties, picnics, fishing parties, &c. We cannot educate, either in our Boarding or Day Schools, pupils who are allowed by their parents to be ‘half way Young Ladies.’ ”[62] Students did enjoy escorted field trips, however. When Jenny Lind came to Nashville to sing at the Adelphi Theater in 1851, the students attended.[63]

Sartorial competition was rife in female academies. Students frequently wrote home asking for new dresses, hats, and shawls to wear. As a consequence, some of the larger schools had to adopt uniforms. Girls did not have to make their own uniforms, but they were responsible for mending them.[64] In 1845 the Columbia Female Institute adopted a daily uniform for boarding pupils, explaining that students “would not sacrifice health at the shrine of fashion.”[65] In the winter, girls were to wear dark purple dresses made of Alpaca or worsted wool with a matching cape, both constructed without trimmings. In the summer the uniforms were blue gingham. The institute had a dressmaker on staff. Boarding students were limited to $50 a semester on clothing. The Odd Fellows Female Institute in Rogersville, Hawkins County, recommended that students wear a blue calico or gingham dress and an apron with a sun-bonnet in the summer. In winter, a blue merino or linsey dress with a white sun-bonnet was required.[66] Rachel Frances Spears supposedly depicted the Odd Fellows Female Collegiate Institute on her sampler in 1857 (Figure 23), although photos of the school show similarities but not an exact match (Figure 24).[67]

A number of female colleges opened in Tennessee in the 1850s. Among these were the Nashville Female College, Davidson County, in 1852; the Odd Fellows Female Collegiate Institute, Gibson County, in 1852; the Memphis Female College, Shelby County, in 1854; the LaGrange Female College, Henry County, in 1855; Tennessee Female College, Franklin, Williamson County, in 1857; and the Mary Sharpe College, Winchester, Franklin County, in 1858. There were more Tennessee and Kentucky male and female college students in 1857 than in any other state in the Union.[68]

For a wealthy few, college was seen as a continuation of refinement that elevated the family status. Ambitious parents desired that their daughters become intellectual and cultural partners in successful marriages. After graduation, many college girls from middle-class families often became teachers until they wed. A number of them continued to teach long after marriage.

The Odd Fellows Female Collegiate Institute in Rogersville, which changed its name to the Rogersville Synodical College in 1892, had an education department specifically for training teachers.[69] The Nashville Female Academy was not the only school to add a collegiate department. When the Knoxville Female Academy decided to add a college curriculum in 1848, the trustees changed the name to the East Tennessee Female Institute. The Columbia Athenaeum achieved college status in 1858 after Rev. Smith’s students tested well alongside male college students in Nashville. The Athenaeum senior department was divided into schools in 1871 which reflected areas of interest. Students could major in ancient languages; modern languages; moral philosophy; civil history; general literature; elocution; English; mathematics; natural philosophy and chemistry; natural history; music; and art. Art could include embroidery and fancy work.

Like the academies, female colleges had oral examinations at the end of the year. Young ladies answered questions and a selected few essays to read. Music students performed, while art and embroidery were on display (Figure 25). Graduates were aged sixteen to eighteen. Depending upon the school, the girls were awarded bachelor degrees or mistress degrees. Isabella M. White earned a Mistress of Polite Literature degree from the East Tennessee Female Institute in 1849 (Figure 26).[70] Songs were even composed and published in honor of graduates, such as “The Buds Have Bloomed to Flowers,” written in 1859 and dedicated to graduates of the Nashville Female Academy (Figure 27).

Southern female academies faced difficulties during the Civil War. Tennessee was the first state to submit to Union occupation in 1862.[71] Many schools closed, and the boarders were sent home. The Nashville Female Academy, the East Tennessee Female Academy, and the Columbia Female Institute became hospitals. The Porter Female Academy in Triune, Williamson County, was burned. The Columbia Athenaeum became headquarters, barracks, and a hospital for the Union Army, but still endeavored to stay open for students.[72] The few remaining girls attended class in the rectory. After the Federals burned one of the buildings, the Confederates pillaged the property, taking bedding, desks, and other items. Some Tennesseans sent their daughters away from the conflict. As previously mentioned, enrollment at the Salem Female Academy in North Carolina, considered a safe location during the war, increased as parents from all over the southern states sent their daughters to board there.

In 1873 the Tennessee State Legislature passed laws to establish a public school system funded by taxation. Nashville and Memphis already had public schools prior to that, but the rest of the state did not. When the war was over many female schools had disappeared. The Nashville Female Academy tried to reopen, but without success. Many southerners could no longer afford to pay tuition for private schools. The Athenaeum in Columbia closed in 1904.[73] The Columbia Female Institute closed in 1932 and burned in 1959; the Knoxville Female Academy/East Tennessee Female Institute ended classes in 1911.[74]

After graduation and marriage, most women had little time for embroidery. They had mending and sewing to occupy them. If a woman did stitch a sampler as an adult, it was usually a family register or a mourning piece that were much less elaborate than the samplers made in schools. But women would use their needlework skills to embroider christening gowns, clothing for themselves and their children, and lingerie. Fancy work that included a variety of stitches flourished on crazy quilts in the later part of the nineteenth century.

Southern schools maintained needlework as part of the curriculum longer than northern schools. In Tennessee the Columbia Athenaeum was still teaching the craft in 1893.[75] In 1889, Sara Blackburn Washington stitched a Berlin work sampler at an unknown school in Nashville (Figure 28).[76] Wool Berlin work, which evolved into needlepoint on canvas, became extremely popular and replaced counted cross stitch.[77]

Needlework had vanished from formal education less than a hundred years after the Pulaski Female Academy’s Rev. Thomason expressed his 1836 goal to “preserve and cultivate the ornamental character of the female sex” through teaching the ornamental arts.[78] Needlework was no longer taught in schools, even as an elective. Cross stitch rose in popularity again in the early twentieth century as part of the Colonial Revival movement. By then the decorative art had become the province of adult hobbyists who often worked from kits and printed fabric instead of mastering their skills as part of the curriculum at female academies.

Folklorist Jennifer C. Core holds master’s degrees from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and Indiana University, Bloomington. She is the president and co-founder of the Tennessee Sampler Survey. Jennifer is the Director of Programs and Membership at the Tennessee Historical Society and can be contacted at [email protected].

Janet S. Hasson has a BFA in Fashion Design from Washington University in St. Louis. She is the retired curator of Belle Meade Plantation, a historic house museum in Nashville, TN, and is the past president of the Southeastern Region of the Costume Society of America. She is the secretary-treasurer and genealogist of the Tennessee Sampler Survey. She can be contacted at [email protected].

[1] W. R. Thomason, “An address on female education, delivered at the close of the session of the Pulaski Female Academy, June, 1836” (Nashville, TN: Joseph Norvell, 1836); available at the Tennessee State Library and Archives, LC1671.T3, Nashville, TN.

[2] Sarah Rogers, “The Beginning of Public Education in Rural Tennessee During the Reconstruction Period,” Rhodes Institute for Regional Studies, 2009.5, online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwis4o-qiYXkAhVGAqwKHV6RBoYQFjAAegQIARAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.amesplantation.org%2Fsites%2F411%2Fuploaded%2Ffiles%2FThe_Beginnings_of_Public_Educaiton_in_Rural_TN_During_the_Reconstruction_Period.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2SH4paxbOHEaCON05sFWDD (accessed 15 August 2019).

[3] For more information about the print “The Schoolmistress at Home” illustrated in Fig. 1, see Yale University Library’s catalog entry: http://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:976469 (accessed 14 June 2019).

[4] Glee Krueger, A Gallery of American Samplers (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1978), 9.

[5] Before the invention of indelible laundry markers, clothing and household linens were marked with the initials of the owner. For the sampler by Eliza Jane Graham illustrated in Fig. 2, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 042, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=042 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[6] Marking samplers were cross stitch, which required the embroiderer to follow a chart or copy a finished piece in order to determine where to put the needle into the fabric and where to pull it out. “Two threads are to be taken each way of the cloth, and the needle must be passed three ways, in order that the stitch may be complete. The first is aslant from the person, toward the right hand; the second is downward, toward you: and the third is the reverse of the first, that is, aslant from you toward the left hand. The needle is to be brought out at the corner of the stitch, nearest to that you are about to make. The shapes of the letters or figures can be learnt from an inspection of any common sampler.” The Ladies’ Work-Table Book Containing Clear and Practical Instruction in Plain and Fancy Needlework, Embroidery, Knitting, Netting and Crochet (New York: J. Winchester, 1844), 60; available online http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29382/29382-h/29382-h.htm#CHAPTER_XIX (accessed 15 August 2019).

[7] Once the sampler was created it could be used as a reference tool for other pieces of embroidery. Some teachers or professional designers created patterns for free embroidery and drew the designs directly on the linen ground. In free embroidery, also called surface embroidery, designs are applied without counting the threads of the ground fabric. This enables the stitcher to create free flowing motifs without the rigidity of cross stitches. Other teachers purchased patterns and pattern books for their students to use.

[8] Tennessee Gazette (Nashville, TN), 13 February 1804.

[9] “Advertisement for Mrs. Long’s School,” Western Weekly Review (Franklin, TN), 3 February 1832.

[10] Academies were also called seminaries or select schools. Institutes were usually college level.

[11] The Nashville Female Academy had an infant school, a prep school, a high school, and a college.

[12] Jeri Hasselbring, “Female Education in Antebellum Williamson County: 1822–1861,” Williamson County Historical Society Journal, vol. 28 (1997): 9.

[13] The Nashville Female Academy, chartered in 1816 in Nashville, and the Salem Female Academy, in Salem, NC, were by far the exceptions.

[14] Jennifer Core, “Salem Female Academy: God’s Acre,” 4 April 2010, Tennessee Sampler Survey, online: http://tennesseesamplers.blogspot.com/2010/04/salem-female-academy-gods-acre.html (accessed 15 August 2019).

[15] At the time the Salem Female Academy was considered to be the most prestigious in the South.

[16] Ledger of the Boarding School for Female Education at Salem, N.C. [1805–1809], 38, Salem College Libraries, Salem Academy and College, Winston-Salem, NC; available online: https://lib.digitalnc.org/record/22477?ln=en&p=Salem+Female+Academy+Ledgers+AND+contributinginstitution%3A%22Salem+Academy+and+College%22#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&r=0&xywh=-1847%2C-245%2C6424%2C4846 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[17] John R. Bumgarner, Sarah Childress Polk: A Biography of the Remarkable First Lady (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1997), 17.

[18] For the sampler by Sarah Childress illustrated in Fig. 3, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 022, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=022 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[19] Charles Frederic Bahnson, Bright and Gloomy Days: The Civil War Correspondence of Captain Charles Frederic Bahnson, a Moravian Confederate, edited by Sarah Bahnson Chapman (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 2007), xl.

[20] Fisk’s Female Academy burned in 1830. John Washington, Moses Fisk, 7 June 2012, online: http://www.scottsdaletrails.com/2012/06/07/moses-fisk/ (accessed 15 August 2019).

[21] Democratic Clarion & Tennessee Gazette (Nashville, TN), 2 March 1810, 4. Needlework and embroidery were part of “fancy work” which also included Berlin work (needlepoint), beadwork, crochet, tatting, pressed flowers, wax flowers, and shell work—skills that would be used to decorate one’s home.

[22] The school was founded in 1816 but did not open until 1817. J. E. Windrow, “Collins D. Elliott and the Nashville Female Academy,” Tennessee Historical Magazine, vol. 3, no. 2 (1935): 79.

[23] The Knoxville Female Academy was chartered in 1811, but it took over a decade to actually open to students.

[24] Hasselbring, Female Education in Antebellum Williamson County, 9–10.

[25] Many of these schools were already defunct by 1860.

[26] Hasselbring, Female Education in Antebellum Williamson County, 10.

[27] Daily Herald (Columbia, TN), 26 January 1997, 17.

[28] The Guardian (Columbia, TN), 1 March 1841, 44. Quoted from Linda Gupton, A Southern Saga, the Story of Franklin Gillette Smith and the Founding of the Columbia Athenaeum (Nashville, TN: Author’s Corner, 2008), 12.

[29] In this sense the word “polite” means refined.

[30] Christie Anne Farnham, The Education of the Southern Belle (New York: New York University, 1994), 126–127.

[31] “Advertisement for the Spring Hill Female Academy,” Western Weekly Review (Franklin, TN), 15 February 1839, 4.

[32] Franklin G. Smith, “School Life,” Guardian: A Family Magazine, vol. 7, no. 3 (15 March 1847): 62–64.

[33] This may have been painted under the instruction of Miss Catherine M. Melville or her sister Mrs. Mitchell. The two sisters immigrated from Edinburgh, Scotland. They taught first in Abingdon, VA, then went to the Jonesborough Female Academy in Washington County. Catherine Melville went on to Bolivar Academy in Monroe County, and finally to the Knoxville Female Academy, Knox County. For the theorem by Mary Henly illustrated in Fig. 9, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 202, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=202 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[34] A reticule is a small purse made of fabric with a flap or a drawstring closing at the top. It is doubtful that the purse was ever completed, as Ann did not leave enough fabric at the top to accommodate a drawstring or flap. For the theorems by Ann P. Bridges illustrated in Fig. 10, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 062, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=062 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[35] For the watercolor by Caroline Walton Allen illustrated in Fig. 11, see Tennessee Sample Survey file TSS 200, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=200 (accessed 2 June 2019).

[36] “Nashville Female Academy Ornamental Department,” Nashville Union & American (Nashville, TN), 25 August 1859, 3.

[37] “The Columbia Athenaeum Faculty,” Guardian (Columbia, TN), 2 February 1861, 1.

[38] Third Annual Catalog and Circular for the Officers and Students of Odd Fellows Female Collegiate Institute: Knoxville, TN: A. Blackburn & Co., 30 June 1853), 27; available at the H. B. Stamps Library, Rogersville, Hawkins Co., TN.

[39] Laura E. Lutrell, “One Hundred Years of a Female Academy: The Knoxville Female Academy, 1811–1846, The East Tennessee Female Institute, 1846–1911,” East Tennessee Historical Society Publication, vol. 12 (1945): 71–83.

[40] J. E. Windrow, “Collins D. Elliott and the Nashville Female Academy,” Tennessee Historical Magazine, vol. 3, no. 2 (January 1935): 14.

[41] For the sampler by Martha Ann Lytle illustrated in Fig. 12, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 193, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=193 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[42] The “Cult of Domesticity” is a modern term that historians use to identify a set of nineteenth-century domestic values.

[43] Wilma Dykeman, ed., Tennessee Women, Past and Present (Memphis,TN: Brunner, 1977), 23.

[44] Nashville Female Academy Catalog, April 1861, Collins D. Elliott Papers on microfilm, Reel 802, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, TN.

[45] Louisa E. Parkes, “Reminiscences of the Old Institute,” Williamson Co. Historical Society Journal, no. 10 (Spring 1979): 45–50. Mrs. Parkes was the daughter of America Word Walker, who made a sampler in 1829, possibly at the Pleasant Grove Academy, which she was known to have attended in 1832. The school was taught by the Taliaferro sisters in their father’s home at Leipers Fork, Williamson Co., TN.

[46] For the sampler by Mary E. Halfacre illustrated in Fig. 13, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 008, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=008 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[47] For the sampler by Isabella S. Wallis Slate illustrated in Fig. 14, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 018, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=018 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[48] For the sampler by Elizabeth Jane Armstrong illustrated in Fig. 15, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 046, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=046 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[49] For the sampler by Telitha Ann Hill illustrated in Fig. 17, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 032, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=032 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[50] For the sampler by Emily W. May done at Mr. and Mrs. Hunt’s Female Academy and illustrated in Fig. 18, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 106, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=106 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[51] For the sampler by Frances Matilda Batey done at Franklin College and illustrated in Fig. 19, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 071, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=071 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[52] Jesse Ellis and his wife Mary Lewis Maum Ellis were originally from Virginia. They married in Kentucky and were settled on two land grants in Sumner County by 1819. If they started a school there, it has yet to be identified.

[53] For the sampler by Ellen Mordant Oldham illustrated in Fig. 20, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 190, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=190 (accessed 15 August 2019). For the sampler by Caroline Frances DeMoss illustrated in Fig. 21, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 089, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=089 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[54] For the sampler by Lamyra Jane Liggett illustrated in Fig. 22, see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 136, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=136 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[55] Farnham, 70.

[56] For some families a finished sampler was the equivalent of a diploma for their daughters. Samplers were framed and placed on parlor walls as proof of a refined education.

[57] Parents wanted moral supervision for their daughters’ protection, and to prevent elopements, which created a social embarrassment for the entire family.

[58] The Nashville Female Academy was located on Vine and McLemore streets, now Ninth Avenue near Church Street, Nashville. TN.

[59] Cited from a Nashville newspaper article by Miriam Brooks, no date, available in the Nashville Room, Nashville Public Library, Nashville, TN.

[60] W. W. Clayton, History of Davidson County, Tennessee, reprint of 1880 edition (Nashville, TN: Charles Elder, 1971), 267.

[61] “Nashville Female Academy,” Daily Chronicle & Sentinel (Nashville, TN), 2 August 1855.

[62] “Advertisement for the Nashville Female Academy,” Nashville City and Business Directory, John P. Campbell, ed. (Nashville, TN: K. G. Eastman & Co., 1859), 246.

[63] Windrow, “Collins D. Elliott and the Nashville Female Academy”: 20.

[64] Some diaries and letters indicate that the girls used seamstresses or purchased what they needed in town.

[65] Gupton, A Southern Saga, 24.

[66] “Odd Fellows Female Institute,” Rogersville Times (Rogersville, TN), 26 June 1851, 1.

[67] The school was also known as the Rogersville Female Seminary. Rachel Frances Spears embroidered the initials “RFS” at the end of the second row of alphabets. For more about Rachel’s sampler (Fig. 23), see Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 143, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=143 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[68] Jeri McLeland Hasselbring, “A History of Female Education in Antebellum Williamson County, Tennessee: A Plan for the Preservation of Its Legacies” (Master’s Thesis, Middle Tennessee State University, 1996), 989.

[69] “From Rogersville,” Comet (Johnson City, TN), 4 January 1894, 1.

[70] Diploma for Isabella M. White (1833–1920), 25 July 1850, Knoxville, Knox Co., TN. Ink on paper; HOA: 13-3/4”, WOA: 15-3/4”. University of Tennessee Libraries, Special Collections, MS 0098, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN.

[71] On 24 February 1862, Nashville, Tennessee became the first Confederate state capital to fall to the Union. “A Time of Troubles,” Tennessee Blue Book: A History of Tennessee – Student Edition, online: https://tnsoshistory.com/chapter6 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[72] Mrs. Smith kept the school open to preserve its charter and tax-exempt status. Gupton, A Southern Saga, 90.

[73] Karen Finley Bailey, “The Columbia Athenaeum School for Young Ladies, 1852–1904,” Historic Maury, vol. 41, no. 2 (2005).

[74] Ibid, 123 and Laura E. Luttrell, “One Hundred Years of a Female Academy: The Knoxville Female Academy, 1811–1846, the East Tennessee Female Institute, 1846–1911,” East Tennessee Historical Society Publications, No. 17 (1945): 83.

[75] Bill signed by Robert D. Smith, principal of the Columbia Athenaeum, shows that Jennie and Josie Strayhorn bought filo and floss in 1893. Bailey, “The Columbia Athenaeum School for Young Ladies”: 136.

[76] For the sampler by Sara Blackmon Washington illustrated in Fig. 28, see the Colonial Dames Sampler Survey, Berlin Work Sampler #126, online: https://nscda.org/historical-activities/samplers/ (accessed 15 August 2019) and Tennessee Sampler Survey file TSS 235, online: https://www.tennesseesamplers.com/viewsampler.php?samp_id=235 (accessed 15 August 2019).

[77] Berlin work was faster than counted cross stitch and the aniline dyes were more vibrant, which gave it greater appeal. Magazines like the Godey’s Lady’s Book and Peterson’s Magazine contained a variety of patterns for Berlin work, which could be worked on punched paper. There were patterns for pen wipers, sewing boxes, pillows, and bedroom slippers. Many ladies stitched mottos on punched paper to decorate their walls.

[78] Thomason, “An address on female education… .”

© 2019 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts