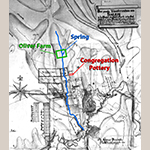

A funeral was held in the Moravian town of Salem, North Carolina in the afternoon of 30 September 1810. The service marked the passing of an esteemed community member, Peter Oliver. Born into enslavement, Peter Oliver became a skilled craftsman and purchased his freedom. Much of the work he undertook to achieve emancipation took place in the pottery workshops of Salem and the nearby town of Bethabara, making him one of the only documented African American potters in the Moravian’s North Carolina communities (collectively known as Wachovia) (Figures 1 and 2).

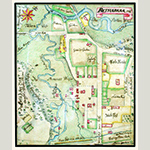

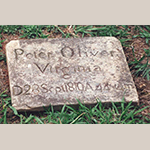

During his lifetime, Peter Oliver was accepted into Salem’s Moravian congregation as a communicant member, a significant achievement integral to securing his freedom. His funeral and the procession that followed were noteworthy in its multiracial character amid an increasingly segregated American South. According to church records, “a large number of Negroes attended, and they were given the front benches” in Salem’s church and “the coffin was carried by Negroes” to the congregation graveyard where Peter Oliver was buried next to his white Moravian brethren in Salem (Figure 3).[1] His dedication to the skills he learned as a craftsman were also celebrated by the community: Peter Oliver was, “true to his calling and work and he brought it about through diligence in his work to the point that he could buy himself free from his status of slavery.”[2]

The African American Moravian craftsman Peter Oliver is well documented, due in part to the Moravian’s thorough recordkeeping. While building on previously published accounts of his life, this article will enrich our understanding of Peter Oliver’s agency as both an enslaved individual and a freedman.[3] Newly discovered archival documents relating to Peter Oliver’s emancipation in Pennsylvania will be studied, as well as recent archaeological work on Lot 38 in Salem, the site of a small kiln and shed used during his tenure in Salem’s congregation pottery. By combining these documentary and archaeological sources, we can more deeply contextualize Peter Oliver’s contributions to the material landscape of Wachovia as well as his life as an African American in Piedmont North Carolina at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Telling and Retelling the Story of Peter Oliver

As an African American craftsman, first enslaved and then free, Peter Oliver has been identified and described in Moravian Church records, by scholars, and in social media posts by many titles. His association with Moravian ceramic production led to his primary portrayal as a potter, a pottery worker, a potter’s assistant, and even a brick maker and builder. However, Peter Oliver also worked in Salem’s Single Brothers’ trades shops, as part of the town’s fire-fighting crew, a gravedigger, sharecropper and farmer, and a supplier of reed stems for tobacco pipes sold through the community store (Figures 4 and 5). He was also a husband and a father. His journey from an enslaved man named Oliver to freedman Peter Oliver, from an unbaptized Stranger (non-Moravian) to a communicant member of Salem’s congregation has been told and retold, remembered and honored, many times since his first appearance in Moravian records in 1784.

Of all the published versions, historian Jon Sensbach’s retellings of Peter Oliver’s life in the pages of the pamphlet African-Americans in Salem and in the book A Separate Canaan remain the most important because of their rigor and humanity.[4] Sensbach provides a critical account of Peter Oliver’s life, contextualizing his experience within the complexities, contradictions, and tensions caused by the Moravians’ participation in slavery and their embrace of racist ideology over time. Just as important, Sensbach highlights the agency of Peter Oliver and his peers, enslaved and free, as they navigated life within the Moravian community, creating opportunities and a sense of autonomy for themselves and their families.

From Stranger to Single Brother

The man we now know as Peter Oliver was born in 1766 in King and Queen County, Virginia, located just east of Richmond.[5] At first, church records in North Carolina referred to him simply as Oliver, an enslaved laborer working in and around the Moravian town of Bethania in 1784 (Figure 6). At this time Oliver was leased to the Moravians by William Blackburne, a non-Moravian slaveowner from Halifax County in Southside Virginia.[6] It is not currently known how long Oliver worked in Bethania prior to 1784. Despite a recent assertion that Oliver made bricks and assisted the mason Johann Gottlob Krause in Salem during this period, there is little evidence to support this claim.[7] However, we do know that he was leased by Michael Ranke, one of the original Moravian settlers of Bethania and the town’s surveyor, and that Oliver may have been assigned to a variety of projects in and around the town.[8] With Oliver’s lease set to expire in 1785, and facing the possibility of being sold to another slaveowner, he asked the Moravians to buy him.[9] Although the Moravians were willing to purchase Oliver, Blackburne was reluctant to sell him and the negotiations went back and forth throughout February 1785.[10] A year later, Blackburne and the church finally came to terms and Oliver was sold to the Moravian congregation in Salem for £100 Virginia currency.[11]

Upon his arrival in Salem, Oliver was assigned a variety of tasks while laboring for the Single Brothers’ Choir.[12] These included working in their trades shops.[13] As he continued to prove himself through his labor and bible study in preparation for baptism, his responsibilities grew. By August, Oliver was assigned to help transport and pump water as part of the town’s fire brigade.[14] Then, in November, Oliver was baptized as Petrus (Peter) Oliver, and officially joined the Single Brothers’ Choir.[15] With his baptism, the man who first came to Wachovia as a rented laborer and Stranger assumed a new, and seemingly paradoxical duel status by today’s standards, as both Peter Oliver the Moravian Single Brother and Peter Oliver the enslaved, legal property of the church.[16]

Becoming a Potter

Despite his status as a Single Brother, in 1788 Peter Oliver was sold again; however, this may have been his plan all along. In June of the previous year, Oliver informed the church of his desire to court a woman enslaved by George Hauser in Bethabara (Figures 7 and 8). Church leaders though insisted he wait until they could provide him with an appropriate match, like they did for other members of the Single Brothers’ Choir.[17] Undeterred, Peter Oliver raised the issue again. This time he suggested traveling to Bethabara to ask Matthaeus (Matthew) Oesterlein, the town’s blacksmith, to buy him. Church leaders relented. If Brother Oesterlein was willing to buy him and George Hauser approved of the courtship, they would not raise any objections.[18] However, after traveling to Bethabara, the plan fell apart. Oesterlein had his doubts and church leaders in Salem decided it was better to wait rather than push the issue on Peter Oliver’s behalf.[19]

Finally, by January of the following year, Peter Oliver prepared to leave Salem for Bethabara. This time, he was sold to Rudolph Christ (pronounced “Krist”), the master potter in Bethabara (Figure 9), and he was sent to learn the potter’s trade.[20] Although only the church could buy or sell enslaved people in Salem during this period, private ownership was allowed in Wachovia’s other settlements such as Bethabara.[21] After agreeing to post a bond for Peter Oliver and promising to sell him if he violated the community’s rules, the pastor in Bethabara, Johann Jacob Ernst, spoke to both men separately about what the church expected from their relationship.[22] Posting bonds for apprentices in Wachovia was a common practice. What made the bond for Peter Oliver unique, and potentially more coercive, was that with its dissolution Peter Oliver faced the very real possibility of being sold back into the broader world of enslavement outside of Wachovia. So, Johann Jacob Ernst explained to Peter Oliver that he was expected to be obedient. To Rudolph Christ, Ernst emphasized the importance of treating Peter Oliver humanely. As a matter of propriety, it was agreed that Peter Oliver would eat with day laborers while Christ’s current apprentice would eat at Christ’s table.[23]

A year later, Rudolph Christ moved from Bethabara to Salem where he took over management of Salem’s congregation-owned pottery (Figure 10). Although Christ brought his family and his apprentice with him, Peter Oliver stayed in Bethabara and was sold to Christ’s replacement at the pottery, Gottlob Krause.[24] Although he continued his work at Bethabara’s pottery, Peter Oliver soon went to church leaders and expressed his concern that, if the opportunity arose, Gottlob Krause might try to sell him. The Aeltesten Conferenz (the board that oversaw the town’s religious and moral matters) responded by suggesting that Krause, like Christ before him, should post a bond ensuring that Peter Oliver would not be sold as long as his behavior conformed to the community’s rules.[25]

In the Workshop of Rudolph Christ

What kinds of pottery did Peter Oliver likely have a hand in making while he was in Bethabara working under Rudolph Christ? In 1964 and 1966, archaeologist Stanley South conducted extensive excavations at Bethabara (Figures 11 and 12). During his work there, South located two pottery waster dumps. The first dump he called the Christ-Krause Waster Dump #1. It contained only wheel-thrown, coarse earthenwares.[26] The second dump, Christ-Krause Waster Dump #2, was located near Monarcas Creek, farther away from Christ’s pottery shop. This dump contained molded “fineware” that South attributed to Christ’s tenure as master potter (Figure 13).[27] So-called “finewares” were popular British-style ceramics made with refined clay. These were mostly molded, as opposed to wheel-thrown, and included popular designs like Queensware, Featheredge, and Royal patterns in plain cream or tortoiseshell exteriors of green, yellow, and brown (Figures 14 and 15). When William Ellis, an English potter trained in the Staffordshire tradition, visited Salem’s congregation pottery in 1773, he taught both Gottfried Aust, Wachovia’s first master potter, and Christ how to make “fineware” (Figure 16).[28] Rudolph Christ’s desire to make “fineware” gave him greater autonomy from working directly under Aust, his old master, in Salem and paved the way for his move to Bethabara where he could establish a workshop of his own.[29] According to South, the quality of these were so fine, in fact, that he had difficulty distinguishing them from fragments of eighteenth-century English imports he recovered during his excavations at Brunswick Town, a British town located on the coast of North Carolina.[30]

South attributed the press-molded “fineware” found in the Christ-Krause Waster Dump #2 to Christ’s workshop rather than Krause’s because church records state that Christ took the molds for these wares with him when he left to become Salem’s master potter in 1789.[31] The molds for many of the “fineware” excavated in Bethabara were probably carved by Christ himself.[32] South was able attribute tortoiseshell pottery fragments found in Bethabara to Christ’s tenure by fitting plate fragments in a mold in Old Salem’s collections with the initials “RC” inscribed on the back (Figures 17 and 18). The sherd had a mottled glaze and Royal creamware pattern shape.[33]

Although several plate molds bear Christ’s name or initials, signed vessels are rare. This makes attributing a given piece to any one potter extremely difficult. One reason may be that, although the pottery shop was managed by an individual master potter, during this period it was a church-owned trade and an extension of the congregation. Signing finished pieces was likely seen as an expression of economic individualism that threatened to undermine the ethos of Christian community the church sought to create. Although Christ probably made many of the molds used to create “fineware” in Bethabara, Peter Oliver could have used them. In fact, he was likely involved in multiple steps that were integral to the process of pottery making and would have mastered the necessary techniques. This much was all but acknowledged when he was sold to Gottlob Krause and Christ asked for an additional payment to compensate for the loss of Peter Oliver, “…whose value has grown since he has learned so much from Br. Christ in the pottery… .”[34]

Work Under Gottlob Krause

Noting that Gottlob Krause spent much of the 1790s engaged with building projects in Salem, in their 2009 Ceramics in America article about Moravian pottery Luke Beckerdite and Johanna Brown put forth the possibility that he may have left Peter Oliver in charge of the pottery during his absence.[35] If true, Beckerdite and Brown further speculate that a significant amount of pottery attributed to Krause during this period may have been made by Peter Oliver.[36] However, because Moravian potters rarely signed their work during this period, there is currently no way to distinguish Peter Oliver’s work from those of the other potters who worked in Krause’s pottery at the time—and we know that Peter Oliver alone did not work in Krause’s workshop. In November 1789, Philip Jacob Meyer, an apprentice under Gottfried Aust and Rudolph Christ, and Gottlob Krause’s brother-in-law, was living in Bethabara before establishing his own pottery in Randolph County in 1793.[37] To date, no documentary evidence has been found showing that Meyer worked in Bethabara’s pottery workshop during this period.[38] However, the presence of another experienced craftsman in town, especially one with close ties to its master potter, could have rekindled Peter Oliver’s earlier fear about being sold, making his position seem even more tenuous than it had before. In addition, there was at least one journeyman potter, Joseph Sturges who worked in Bethabara from roughly the end of 1794 until May 1795, when he left to return to Pennsylvania.[39] By September 1795, Peter Oliver was no longer working in Krause’s shop because, “…for some time Oliver has not gotten along well with his master.”[40] Come November, Krause had replaced both men with a new apprentice, Johann Heinrich Feiser, that he took on a trial basis.[41]

Return to Salem

The relationship between Peter Oliver and Gottlob Krause became so strained that in September 1795 church leaders had to intervene. Krause requested that Johann Jacob Ernst, who had overseen Peter Oliver’s sale first to Rudolph Christ and then to Krause, take him back hoping to rent him to someone in Salem.[42] By this point Peter Oliver had left Krause’s pottery shop in Bethabara and was working on a farm for Samuel Stotz, who was also Salem’s Vorsteher (the community supervisor and treasurer).[43] Two months later, in November 1795, Salem’s Aufseher Collegium (the board that oversaw congregation-owned trades and businesses) raised the issue of Peter Oliver again because he was “…still asking and praying to be taken into the pottery.”[44]

Peter Oliver’s petition could not have come at a better time. Just two years earlier, Rudolph Christ expanded the congregation pottery when he built a small kiln and shed on the east side of Main Street to experiment with the manufacture of new wares, including faience.[45] By April 1795, Christ added the position of graveyard supervisor to his list of responsibilities.[46] This was no small task given the need to keep Salem’s God’s Acre (the Moravian term for their cemeteries) orderly throughout the year and especially in preparation for the annual Easter Sunrise Service (Figure 19). In September he was tasked with helping to procure a new wooden bridge across Peters Creek.[47]

On top of all this, Christ had been dealing with John Butner, an especially unruly apprentice. So, at this meeting of the Aufseher Collegium, issues involving the congregation pottery took up a good portion of the agenda. First, Christ showed off a piece of stoneware, one of the first successful attempts at new wares to come out of the pottery since its expansion.[48] With this piece of good news out of the way, he soon turned to the issue of John Butner, whose behavior was so bad that Christ was ready to officially end Butner’s apprenticeship early which would also mean that he would be expelled from Salem.[49] So, when Peter Oliver, a man that Christ had personally trained and likely trusted, became available, Christ recognized it as an opportunity to secure some much needed and reliable help.

Now a member of Salem’s Aufseher Collegium, Christ suggested employing Peter Oliver in the pottery doing day work. However, like all non-Moravian day workers, Oliver could always be dismissed if he caused any trouble.[50] The collegium agreed and added the following caveat: “Br. Ernst should give an order to a Brother in the community here to take over the owner’s rights of the Negro, so that it does not seem as if he is offering himself, which would be against the laws of the country.”[51] Returning to Salem and working in the congregation pottery may have been Peter Oliver’s idea—a pragmatic solution for all concerned—but church leaders were keenly aware that they needed to conform to the mores of the surrounding slave-owning society. By January 1796, Peter Oliver had returned to Salem when he was recorded helping in the attempted rescue of William Hall during a flood.[52]

Work in Salem’s Congregation Pottery

By 1796 Peter Oliver was working in Salem under Rudolph Christ once more.[53] What exactly Peter Oliver did while he worked in Salem’s pottery, however, is unclear. Like most potters and pottery workers, their daily tasks were rarely recorded. Pottery apprentices, of course, would have been exposed to most of the necessary tasks involved in making pottery as part of their training. The expectations for journeymen, because of their experience, could include managerial tasks, including the supervision and teaching of apprentices. Given Peter Oliver’s experience and knowledge—something that was acknowledged earlier when he was sold to Gottlob Krause in Bethabara—it seems unlikely that he was employed to perform the kinds of menial tasks often assigned to unskilled pottery workers and helpers. Had Christ employed him to perform only menial tasks, it would have been a waste of Peter Oliver’s knowledge and skill, much of which Christ had taught him.

Exactly how long Peter Oliver worked in the congregation pottery after his return to Salem is unknown. Except for visiting journeymen like William Ellis, the annual inventories for the pottery usually do not list the salaries or names of apprentices and journeymen. Instead, researchers must piece this information together from the records kept by various church boards. Had there been a change in the original plan for Peter Oliver’s employment in daily work, or had he transferred to another trade, it seems unlikely it would not have at least warranted a passing note in the minutes of the Aufseher Collegium or the Aeltesten Conferenz.

Archaeological Investigation of the 1793 Kiln on Salem Lot 38: Contextualizing Peter Oliver’s Time in the Congregation Pottery

With the help of several student interns and community volunteers, a series of archaeological excavations were conducted on Lot 38 from 2016 until 2018. As part of this author’s doctoral research through the Department of Anthropology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and ongoing archaeological research by Old Salem Museums & Gardens, we searched for any evidence of the kilns or supporting structures built on the east side of Main Street (Figure 20).[54]

The excavation located the remains of Christ’s small kiln and shed built in 1793 (Feature 13) and used until 1805 when it was replaced by a larger kiln.[55] A structure was revealed that had been robbed of its reusable brick and stone, thoroughly demolished, filled with layers of building debris and pottery-related discard, and capped by a compacted work surface (Figure 21).

Despite the condition of this structure, labeled Feature 13, ceramic sherds and fragments of kiln furniture were recovered that offer valuable insight into the kinds of pottery produced during Peter Oliver’s likely tenure. Moreover, the excavation showed that the bottom of the kiln itself was dug down approximately two feet into the surrounding clay subsoil, providing clear evidence for the earliest known construction of a semi-subterranean kiln in Salem.

During the excavation of Feature 13, several sherds of utilitarian pottery were recovered. These were wheel-thrown and consisted of coarse earthenware with lead-glazed interiors and unglazed exteriors. There were enough fragments to almost reconstruct two whole vessels completely: a large double-handled serving pot and a smaller cream pot (Figure 22). The base of the cream pot included a price mark (Roman numeral II with a diagonal line between each downstroke from dragging the stylus). Price marks such as this one have been attributed to Rudolph Christ’s tenure at both the Bethabara and Salem potteries.[56]

In addition to utilitarian vessel fragments, fragments of decorative trailed slipware were recovered. These coarse earthenware plates and dishes were wheel-thrown and commonly exhibit stylized flowers on the cavetto and bordered by sine waves within one or more bands on the marly. In addition to their aesthetics, it has been argued that the flowers themselves carried important religious meaning to the Moravians (Figure 23).[57]

Like utilitarian vessels, plates and dishes with trailed slip decoration were made of coarse earthenware and formed with a potter’s wheel. However, before being glazed and fired, potters applied and painted intricate patterns of colorful slip on the interior surface. The vessels with their newly added slip were then fired in a kiln, which removed the last of the water from the bodies, making them hard and setting the slip. A glaze of ground silica with lead added as a flux was then applied to the surfaces of these new bisque- or biscuit-fired pieces. Then, the vessels were placed in the kiln for a second time. This glaze, or glost, firing fused the glaze to the vessels and created a clear waterproof coating.[58]

Peter Oliver would have been quite familiar with this process and participated in at least some if not all the necessary steps. Many curated examples of trailed slipware attributed to the hand of Gottfried Aust or Rudolph Christ contain flowers with stems that start at the lower right, make a subtle s-shaped curve, and terminate pointing toward the left at the top (Figures 24 and 25). The stem in the example on the right side in Fig. 23 begins with an orientation towards the lower left. This suggests it may have been made by a different potter working in Salem’s congregation pottery at the time. Perhaps this piece was made by one of Christ’s apprentices or journeymen, or even Peter Oliver himself. On the bottom of the same vessel there is a partial price mark but no signature or initials, so the identity of its maker remains a mystery.

Fragments of stub-stemmed tobacco pipes were also recovered from Feature 13. These pipes were a steady source of revenue for Moravian potters (Figure 26). As a result, the pottery periodically outsourced their production to elderly or infirm members of the community who needed extra money.[59] When not made locally, the pipe molds could be obtained through other Moravian settlements like Christiansbrunn in Pennsylvania.[60] Because the pipes required the addition of a reed, these needed to be cut and potentially sold alongside the pipes. Peter Oliver understood how to make these ubiquitous pipes and probably pressed many of them himself in Salem’s pottery. Later in life he drew upon this experience and became an independent supplier of reeds and stems for tobacco pipes sold through Salem’s community store.[61]

Construction of a new kiln on Lot 38 was motivated by the 1793 visit of Carl Eisenberg, an itinerate German potter, who showed the Moravians how to make faience.[62] Faience was a popular lead-glazed, European ceramic with tin added to produce a finish that resembled porcelain (Figures 27 and 28).[63] When Eisenberg concluded his brief stint in Salem’s congregation pottery, he left behind a hand-written glaze recipe book for Christ to follow.[64] Several sherds of faience from in and around the 1793 kiln were recovered during excavation (Figure 29). Some examples, like the ring bottle fragment illustrated to the left in Fig. 29, were already known from previous archaeological work, such as another ring bottle illustrated in Figure 30. Others, like the hollowware sherds illustrated on the right, were new discoveries. The variety on these sherds, beyond the blue green on ring bottles, reflects a fuller range of colors provided in Eisenberg’s glaze recipe book.

It was the Salem congregation pottery’s expansion on to Lot 38 and the newly built kiln there that provided the opportunity and a justification for Peter Oliver’s return to Salem. Rudolph Christ had convinced church leaders to support the new venture, the cost of which would have to be repaid over time.[65] As Salem’s town administrator Frederic William Marshall stated in 1793, the new kiln was needed because “usually each new line draws new customers, and there are potters enough around us where they would otherwise go.”[66] At the 1795 meeting of the Aufseher Collegium, Christ had shown he could successfully make stoneware.[67] Now, he needed help increasing production on both sides of Main Street, especially if he was going to produce those “new lines” of pottery that would attract new customers. To do this, Christ needed someone with experience that he could trust, especially given apprentice John Butner’s recent disobedient behavior. In this regard, Peter Oliver’s desire to return to Salem aligned with Rudolph Christ’s need for dependable labor.

From Salem to Pennsylvania, from Enslavement to Freedom

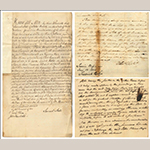

On 2 March 1799 Peter Oliver became a communicant member of the Moravian congregation in Salem.[68] Six months later, in September, Johann Jacob Ernst sold Peter Oliver again, back to Salem’s Vorsteher Samuel Stotz.[69] In mid-January 1800, Peter Oliver was sold once more, to be enslaved to Peter Lehnert, a Moravian from Pennsylvania who was visiting Salem.[70] Later that spring, Lehnert and Oliver set out for Pennsylvania, a state where importing enslaved labor was illegal. After their arrival in June, Peter Oliver went to the courthouse in Lancaster County where he petitioned the court for his freedom which was granted by Judge Frederick Kuhn (Figure 31).[71]

The document that freed Peter Oliver from bondage was until recently unknown. It was discovered by Martha Abel through her research at LancasterHistory in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Her 2018 blog post about Peter Oliver was then brought to the author’s attention by Mary Comer, an educator at Old Salem Museums & Gardens.[72]

Bills of sale are meant to legitimize economic transactions that transform things into commodities. For the enslaved they functioned to legitimize the legal transformation of people into commodities; they transformed subjects into objects. In a bill of sale, those who do the buying and selling are active, what or who is being bought and sold are passive. In the case of enslavement, they attempted to strip the enslaved of their agency. When Judge Frederick Kuhn was presented with the bill of sale for Peter Oliver and his signed affidavit, Peter Oliver stood in the courtroom reasserting his agency over a document designed to strip him of his humanity. It was a symbolic act but one with very real consequences. This episode serves as a reminder that historical documents are neither simply records of events in the past nor things to be mined for information in the present: Documents shaped the lives of living people and the roles they served and could also be used to deconstruct and remake their identities.[73]

The circumstances surrounding Peter Oliver’s sale to Peter Lehnert and their journey to Pennsylvania remain mysterious. To date no additional documents relating to this episode have been found in the church archives. It seems reasonable to infer that Peter Oliver’s journey to the North to attain his freedom was not part of a clandestine plan of which only he was aware. His enslaver Peter Lehnert and possibly others in Salem were complicit. When Peter Oliver returned to Salem in July 1800, the Aeltesten Conferenz rather nonchalantly noted his new status as a free man.[74] Had he traveled to Pennsylvania and secured his freedom surreptitiously, it is unlikely that church leaders would have allowed his return to Salem and fellowship in its congregation.

One clue concerning what may have happened lies in Peter Oliver’s memoir, written at the time of his death. In the memoir, Peter Oliver is described as “…true in his calling and work and he brought it about through diligence in his work to the point that he could buy himself free from his status of slavery.”[75] This suggests the possibility that Peter Oliver may have used the money he earned working in the congregation pottery to finance his sale to Peter Lehnert. An additional clue comes from the experience of another enslaved man living in Wachovia, Johann Samuel. In May of 1795, church leaders discussed the possibility of freeing Johann Samuel. His wife would soon be free, and Johann wanted to be freed along with their children, to which the Aeltesten Conferenz noted that legally their emancipation would be very difficult.[76] By 1797, after his wife had been freed, their children were bound out until they were old enough to be freed.[77] The issue of emancipating Johann Samuel was raised again in 1799, but complicating matters was the fact that it required an act of North Carolina’s general assembly to do so.[78] Ultimately, an act freeing Johann Samuel was passed but not until February 1801, six years after the issue was first raised.[79]

Peter Oliver and Johann Samuel knew one another in Bethabara. Johann Samuel was friends with Peter, the brother of the woman that Peter Oliver wanted to court in Bethabara.[80] Johann Samuel worked as a supervisor at the congregation plantation in Bethabara when Peter Oliver worked in the pottery there.[81] And in 1804, as communicant members of the church, they both served as sponsors for the baptism of John Immanuel, an enslaved member in Bethania.[82] So, as Johann Samuel sought his own freedom, Peter Oliver likely followed his experience with great interest.

If emancipating Johann Samuel could be a difficult and drawn-out legal process, even with the support of church leaders, then Peter Oliver may have looked for, even devised, a more expedient route to secure his freedom. Traveling to a state where his freedom was guaranteed might require a long and potentially dangerous journey through the slaveholding South outside of Wachovia, but the process itself might be faster and it would certainly attract less attention from state authorities who might suspect the Moravians were really abolitionists like their Quaker neighbors.[83] As long as the church was paid, Peter Oliver could leave Salem. He would then travel from the relative safety of one Moravian community to another. With Peter Lehnert, a white Moravian, as escort and under the guise of being his property with a bill of sale as proof in case they were stopped by a patrol looking for runaway slaves, they made their way to Pennsylvania. Peter Oliver also needed a bill of sale to make his case for freedom in front of a judge once they arrived.

Overseeing the transaction between the church and Peter Lehnert was Samuel Stotz. It was Stotz who initially bought Peter Oliver from Blackburne on behalf of the Single Brothers’ Choir in 1786.[84] It was Stotz that sold him to Rudolph Christ in 1788 so he could travel to Bethabara and learn the potter’s trade.[85] And it was Stotz who Peter Oliver worked for after he left Krause’s pottery shop before returning to Salem.[86] Now Stotz was selling him to Peter Lehnert.[87] Beyond his necessary involvement as Vorsteher, Samuel Stotz was familiar with Peter Oliver’s life in Wachovia, including its ups and downs. And Samuel Stotz would have been among the first church leaders informed upon his return.

We do not know, of course, whether Peter Oliver’s trip to Pennsylvania was intentionally planned to free him of bondage. It is a plausible, perhaps even likely, scenario given the fragmentary evidence available. Regardless, neither Peter Lehnert nor Peter Oliver appears to have faced any negative repercussions for their respective roles. Peter Lehnert, acting as the importer of an enslaved person into the free state of Pennsylvania, was not charged, reprimanded, or fined. Peter Oliver was accepted back in Salem with only a passing reference to his new legal status. That alone suggests some degree of collusion among all parties involved.

After Freedom

After Peter Oliver returned to Salem as a free man he enlisted the help of church officials to arrange a marriage proposal.[88] With few suitable prospects in Wachovia, Oliver traveled back to Pennsylvania in 1801 to look for a wife from among the Moravian congregations there.[89] The trip proved unsuccessful.[90] The following year, Peter Oliver turned his attention towards courting Christina Bass, a local non-Moravian and free woman of color.[91] Despite the church’s concern that marriage to a Stranger might lead Peter Oliver away from the congregation, they nonetheless allowed the courtship to proceed.[92] The couple were soon married by the justice of the peace.[93] Soon after, they moved to a farm located just north of town which they rented from the church.[94] Christina Bass Oliver then joined the congregation and worshiped at Salem’s church with her new husband.[95]

By 1802, Peter Oliver had achieved much of what he had set out to do when he first arrived in Wachovia eighteen years earlier. He was married. He had the use of land and the autonomy to make a living for himself and the family that he and Christina wanted. He had built a support network among his fellow Moravians, Black and white, enslaved and free, in and around Salem. And, above all, he was free.

We do not know if Peter Oliver returned to work in the congregation pottery. There are no known records to indicate that he did. It seems unlikely, especially given the amount of work needed to sustain a farm. Could he have made and fired pottery on the land that he leased? Perhaps. Peter Oliver had the skills to do so. An individual did not necessarily need to complete a formal apprenticeship and pay their dues as a journeyman potter to start their own workshop. Philip Jacob Meyer, apprentice under Gottfried Aust and Rudolph Christ, was asked to leave Salem before he could become a journeyman potter.[96] And yet, Meyer went on to establish a pottery near Mount Shepherd in Randolph County.[97] Another example was Frederick Rothrock, whose modest but successful pottery venture was noted in the Friedberg Diary in 1793 (Figure 32).[98]

What Meyer and Rothrock had in common was their distance from Salem. By moving far enough away from Salem they did not pose an immediate economic threat to the congregation pottery. They also had money, possibly saved from their apprentice wages, to purchase the tools and supplies (including the building of a kiln) needed to make pottery.[99] Although Peter Oliver had the ability to practice the lucrative trade for which he had been trained, his farm was too close to Salem and he probably lacked capital.

At four and one-fourth acres, the farm he leased north of Salem certainly had room to support a modest pottery operation.[100] And it was far enough removed that the smoke from kiln firings would not become a nuisance to Salem’s residents. However, it was only a short walk from the congregation-owned pottery and Rudolph Christ’s workshop (Figure 33). If Peter Oliver had set up an independent pottery, especially one on church-owned property that might cut into the profits from one of its trades, then the church would have cause to cancel his lease. Add to this the potential of alienating a respected and influential member of the congregation like its master potter Rudolph Christ and going against the church would have been a risky proposition indeed.[101]

In terms of capital, if the three hundred, thirty-five dollars paid by Peter Lehnert to Samuel Stotz came from Peter Oliver’s earnings while working in the congregation pottery, then it represented a substantial outlay of cash. This is money that Peter Oliver otherwise could have used to establish his own pottery. Even if these funds came from another source, the money Peter Oliver used to purchase his freedom as noted in his memoir represented an additional expense. This was an expense not required of newly independent apprentices or journeyman seeking to establish their own shops and it would have placed Peter Oliver at a distinct disadvantage.

We do know that Peter Oliver’s life as a free man was a struggle. The summer after he married Christina Bass Oliver, he fell seriously ill.[102] The next year Peter Oliver was approved as a grave digger for the church.[103] Despite this potential supplement to his income, in 1805 he asked the church to lower the rent on his farm. The church declined.[104] To provide for himself and his growing family, Peter Oliver drew on his previous experience as a potter and farmer in creative ways. He cut reeds and stems for tobacco pipes that were sold through the community store.[105] The need for good quality reeds for stub stemmed tobacco pipes was something he was all too familiar with from his earlier work in the pottery workshops in Bethabara and Salem. And the spring that ran through his farm may have provided an ample supply. He also kept bees and possibly sold their honey. The probate inventory taken after his death lists “bee gums,” a southern colloquial term for beehives.[106]

Despite the economic hardships, Peter and Christina Oliver made a life for themselves and their family. They had six children, three of whom died young and were buried in Salem’s congregation graveyard.[107] In 1810, ten years after securing his freedom, Peter Oliver died at the age of forty-four years (Figure 34).[108] Controversary engulfed the Oliver family after his death. Two of the children, Nancy and Israel, were contracted out to live with other families.[109] The church then canceled the lease on the farm over an alleged improper relationship between the widow Christina Oliver and a man named John Immanuel.[110] Although Nancy and Israel remained in the Salem area, it is not known where Christina went after her expulsion from the Moravian community.[111]

Conclusion

Peter Oliver may have come into the world enslaved, but he was determined to leave it as a free man. To achieve that goal, he employed an ingenious strategy. Where and when possible, he would affect the buying and selling of himself so that each exchange might bring him closer to his goal. Time and again it was Peter Oliver who approached potential owners to suggest a new arrangement that might benefit them and, more importantly, make the circumstances of his own enslavement more bearable. It was Peter Oliver who asked the Moravians to buy him in 1785 to avoid the possibility of being sold elsewhere. Then, having gained a degree of security and his new status as a Single Brother in Salem, he approached church officials with the possibility of selling him to a church member in Bethabara where he might find a wife. In 1787 he traveled to Bethabara to pitch the idea to his potential buyer himself. When this plan failed, he was sold to the potter Rudolph Christ. The result was that he was able to move to Bethabara as he wished and also learned valuable skills in Christ’s pottery.

When he was sold again, this time to Bethabara’s new potter, Gottlob Krause, Peter Oliver feared he would be traded away from Wachovia. As a result, he appealed to church officials who then took steps to avoid this outcome. After his relationship with Krause deteriorated to the point that he left Krause’s workshop, Peter Oliver went to church leaders once again—this time to revisit the possibility of his return to Salem. The expansion of the Salem congregation pottery across the street to Lot 38, and the newly built kiln, provided the justification for Rudolph Christ to convince church leaders that Peter Oliver’s skills were desired if the new venture was to succeed.

Once back in Salem, Peter Oliver took advantage of his new position doing “daily work” in the congregation pottery. He employed the experience and knowledge learned from Christ and Krause in Bethabara’s pottery, likely assisting in the production of utilitarian and fine wares, as well as the “new” lines of faience being produced in the kiln on Lot 38. He then took the next step and became a communicant member of Salem’s Moravian congregation. Peter Oliver was then able to use the opportunities afforded by working in the congregation pottery and life in Salem to purchase his freedom and secure it in Pennsylvania through his sale to Peter Lehnert. This may have been his idea as well.

Perhaps the ultimate expression of Peter Oliver’s agency and strategy to bend the practice of buying and selling human beings to his own advantage, came when he appeared in a Lancaster County courtroom in 1800 to argue for his freedom. As proof that he had indeed been enslaved and was imported to Pennsylvania for that purpose and against its law, Lehnert produced Oliver’s bill of sale for the judge’s inspection.[112] With his bill of sale and the resulting judge’s order, his status was radically transformed. Taking a document designed to dehumanize, Peter Oliver wielded it like a fulcrum to shift his legal status from enslaved to free.

Geoff Hughes is an archaeologist and doctoral candidate at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. His dissertation revealed and contextualized the experimental pottery kiln on Lot 38 in Salem. He can be contacted at [email protected].

[1] Extracts from the Salem Diary, 30 September 1810, in Adelaide L. Fries, ed., Records of the Moravians in North Carolina, Vol. 7: 1809–1822 (Raleigh, NC: Department of Archives and History, 1947), 3112.

[2] “Memoir of Peter Oliver, 1810,” translated by Frank P Albright, Moravian Church Archives, Southern Province, Winston-Salem, NC. This quote comes from Peter Oliver’s memoir, or Lebensläuf, a short biographical account read to the congregation and archived by the church after a member’s death. For more on the Moravian Lebensläufe, see C. Daniel Crews, Moravian Meanings: A Glossary of Historical Terms of the Moravian Church, Southern Province, second edition (Winston-Salem, NC: Moravian Church Archives, Southern Province, 1996), 17.

[3] Although published references to Peter Oliver’s life appeared in Adelaide Fries’s edited volumes of Moravian church records in the 1940s and brief accounts were included in John Bivins’s 1972 book on Moravian pottery and Stanley South’s archaeological research findings it was not until the publication of Jon Sensbach’s pamphlet and subsequent book in the 1990s that Peter Oliver’s life was examined in detail. More recently, Peter Oliver has been referenced in articles by Johanna Brown and Luke Beckerdite in Ceramics in America and Nathan Love in the MESDA Journal as well as a book on Moravian earthenware by Stephen Compton, and in blog posts as well as on social media. Adelaide L. Fries, ed., Records of the Moravians in North Carolina, Vol. 5 (1784–1792), Vol. 6 (1793–1808), Vol. 7 (1809–1822) (Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Historical Commission and Department of Archives and History, 1941, 1943, 1947); John Bivins Jr., The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, 1972); Stanley A. South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia: Excavating Eighteenth-Century Bethabara and Moravian Pottery (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999); Jon F. Sensbach, African-Americans in Salem; Brother Abraham: An African Moravian in Salem; Peter Oliver: Life of a Black Moravian Craftsman (Winston-Salem, NC: Old Salem, 1992); A Separate Canaan: The Making of an Afro-Moravian World in North Carolina, 1763–1840 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, 1998); Luke Beckerdite and Johanna Brown, “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina: The Moravian Tradition Reconsidered,” Ceramics in America, 2009, eds. Robert Hunter and Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2009), 2–67, available online: https://chipstone.org/article.php/449/Ceramics-in-America-2009/Eighteenth-Century-Earthenware-from-North-Carolina:-The-Moravian-Tradition-Reconsidered (accessed 5 October 2022); Nathan Love, “The Men Who Built Salem: A Biographical Look at the Builders of the North Carolina Moravian Town,” MESDA Journal, Vol. 37 (2016), online: https://www.mesdajournal.org/2016/the-men-who-built-salem-a-biographical-look-at-the-builders-of-the-north-carolina-moravian-town/ (accessed 5 October 2022); Stephen C. Compton, North Carolina’s Moravian Potters: The Art and Mystery of Pottery-Making in Wachovia, America Through Time Series (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2019); Martha Able, “How Peter Oliver freed himself,” LancasterHistory archives blog, online: https://www.lancasterhistory.org/peter-oliver-freed/ (accessed 5 October 2022).

[4] Sensbach, African-Americans in Salem; Sensbach, A Separate Canaan.

[5] “Memoir of Peter Oliver, 1810.”

[6] Aeltesten Conferenz, “Minutes of the Elder’s Conference (Salem, NC),” 15 August 1784, translated by Frances Cumnock, Moravian Church Archives, Southern Province, Winston-Salem, NC (original minutes also at the Moravian Church Archives, Southern Province, Winston-Salem, NC).

[7] According to historian Nathan Love, during 1784 and 1785 “Oliver worked on projects with the mason Johann Gottlob Krause … He helped Krause rebuild the Salem Tavern … likely aiding in the burning or laying of bricks. The tavern was completed in December 1784 but Oliver was still in Krause’s employ however two months later, possibly working on the construction of the Gottlieb Schober House, begun in January 1785” (Love, “The Men Who Built Salem”). It seems likely that Love mistook John Krause of Bethania for the potter Johann Gottlob Krause. In the records the potter Krause is consistently referred to as “Gottlob Krause,” not “John” or “Johann” (Fries, Records of the Moravians in North Carolina, Vol. 2, pp. 2107, 2137, 2150, 2156).

[8] C. Daniel Crews, Faith, Hope, Love: A History of the Unitas Fratrum (Winston-Salem, NC: Moravian Church Archives, Southern Province, 2008), 34–35, 173.

[9] “Memoir of Peter Oliver, 1810.”

[10] Fries, “Bethania Diary,” 10-21 February 1785, Vol. 5, 2107–2108.

[11] Although the equivalent amount of £100 Virginia currency was reported to the other church boards, the Single Brothers’ Diacony paid Blackburne £133.6.8 in North Carolina currency for Peter Oliver. “Bill of Sale for Oliver, 1786,” 18 February 1786, Moravian Church Archives, Southern Province, Winston-Salem, NC; Tanya Thacker, “African-American References Wachovia/Salem, NC,” manuscript, 1994, Gray Library, Old Salem Museums & Gardens, Winston-Salem, NC; Aufseher Collegium, “Minutes of the Aufseher Collegium (Salem, NC), 1772-1829 & 1833-1856,” translated by Erika Huber, Gray Library, Old Salem Museums & Gardens, Winston-Salem, NC (original minutes at the Moravian Church Archives, Southern Province, Winston-Salem, NC).

[12] Choirs were at the core of Moravian communities. Unrelated to singing or music, the Moravian choirs were groups of individuals in the congregation bonded by age, gender, or marital status. Members of each choir came together, and sometimes lived together, for spiritual growth as well as sharing responsibilities of life within the church and town. Choirs included the Single Brothers, Single Sisters, Married Brothers, Married Sisters, Widowers, Widows, Older Boys, Older Girls, Little Boys, Little Girls, and Infants. The Single Brothers and Single Sisters choirs collectively operated trades and businesses to support themselves. See Penelope Niven, Old Salem: The Official Guidebook, third rev. ed. (Winston-Salem, NC: Old Salem, 2011), 11.

[13] “Memoir of Peter Oliver, 1810.”

[14] Aufseher Collegium, 4 August 1786, 1 May 1787.

[15] Aeltesten Conferenz, 12 November 1786.

[16] “Memoir of Peter Oliver, 1810”; Aeltesten Conferenz, 12 November 1786.

[17] Aeltesten Conferenz, 20 June 1787.

[18] Ibid, 22 August 1787.

[19] Ibid, 30 August 1787.

[20] Ibid, 9 January 1788, 16 January 1788.

[21] Sensbach, A Separate Canaan, 30.

[22] Thacker, “Bond Rudolph Christ to Christopher Kuehnast for £100 Specie Concerning His Negroe Peter Oliver, 6 February 1788,” in “African-American References Wachovia/Salem, NC.”.

[23] Aeltesten Conferenz, 16 January 1788.

[24] Aufseher Collegium, 6 January 1789.

[25] Aeltesten Conferenz, 21 January 1789.

[26] South, 282.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam: The History of William Ellis of Hanley,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts Vol. 17, No. 2 (November 1991), 81–113; available online: https://archive.org/details/journalofearlyso1721991muse/journalofearlyso1721991muse (accessed 5 October 2022).

[29] Aufseher Collegium, 12 September 1780; Beckerdite and Brown, 33; Bivins, 32–33; South, 276–277.

[30] South, 344.

[31] Ibid, 285.

[32] Ibid, 273, 280.

[33] Ibid, 282.

[34] Aufseher Collegium, 6 January 1789.

[35] Beckerdite and Brown, 44.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Fries, “Bethabara Diary, 1789,” Vol. 5, 2286; L. McKay Whatley, “The Mount Shepherd Pottery: Correlating Archaeology and History,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts Vol. 6, No. 1 (May 1980), 40–41; available online: https://archive.org/details/journalofearlyso0601muse/journalofearlyso0601muse (accessed 5 October 2022).

[38] Alain C. Outlaw, “The Mount Shepherd Pottery Site, Randolph County, North Carolina,” Ceramics in America, 2009, eds. Robert Hunter and Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2009), 164; available online: https://chipstone.org/article.php/453/Ceramics-in-America-2009/The-Mount-Shepherd-Pottery-Site,-Randolph-County,-North-Carolina (accessed 5 October 2022).

[39] Fries, “Bethabara Diary, 1794” and “Bethabara Diary, 1795,” Vol. 6, 2521, 2546.

[40] Fries, “Bethabara Diary, 1795,” Vol. 6, 2547.

[41] Ibid.

[42] C. Daniel Crews and Richard W Starbuck, With Courage for the Future: The Story of the Moravian Church, Southern Province (Winston-Salem, NC: Moravian Church Archives, Southern Province, 2002), 854; Fries, Vol. 6, 2541, 2547; Aufseher Collegium, 22 September 1795.

[43] Fries, Vol. 6, 2547; Aufseher Collegium, 22 September 1795.

[44] Aufseher Collegium, 3 November 1795.

[45] Frederic William Marshall, “Report of Frederic William Marshall to the Unity Vorsteher Collegium, 1793,” in Fries, Vol. 6, 2484.

[46] Aufseher Collegium, 7 April 1795.

[47] Ibid, 22 September 1795.

[48] Ibid, 3 November 1795.

[49] Ibid, 3 November 1795. Rudolph Christ’s threat must have worked because John Butner finished out his apprenticeship in Salem and eventually went on to become the master potter in Bethabara.

[50] Ibid, 3 November 1795.

[51] Ibid, 3 November 1795.

[52] Fries, Vol. 6, 2557–2561.

[53] “Memoir of Peter Oliver, 1810”; Aufseher Collegium, 3 November 1795. Church records do not specify when Peter Oliver began working in the congregation pottery after his return to Salem, nor do they list his tasks as a day worker while he was there. Although Rudolph Christ did not lose John Butner as an apprentice, it is still reasonable to assume that Peter Oliver worked in the pottery in some capacity because church records are consistent in recording the comings and goings of congregation members assigned to trades. Although the actual names of Strangers (non-Moravians) employed in church trades may have alluded record keepers from time to time, had someone as well known to the Aufseher Collegium and Aeltesten Conferenz as Peter Oliver been reassigned, it seems unlikely that church leaders would not have commented about it, especially since his return was predicated on Christ’s offer of employment.

[54] A plan for archaeological work at Lot 38 can be found in a Certified Local Government project report completed by Michael O. Hartley and Martha B. Hartley: “Old Salem Archaeology: Protocols for Component Evaluation,” pp. 26-50, Old Salem Museums & Gardens, August 2007; a copy is held in the Anne P. and Thomas A. Gray Library, Old Salem Museums & Gardens, Winston-Salem, NC.

[55] Aufseher Collegium, 2 July 1793, 3 December 1805; Marshall, 2484.

[57] Beckerdite and Brown, 47–61.

[58] For a detailed discussion of ceramic materials and Moravian pottery-making techniques, the reader is directed to Bivins, 73–112.

[59] Aufseher Collegium, 1 January 1783, 13 January 1789; Aeltesten Conferenz, 4 October 1802.

[60] Whatley, 52.

[61] Thacker, “Community Store Letter Book,” in “African-American References Wachovia/Salem, NC.”

[62] Aufseher Collegium, 21 May 1793.

[63] Marshall, 2484.

[64] Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Carl Eisenberg’s Introduction of Tin-Glazed Ceramics to Salem, North Carolina and Evidence for Early Tin-Glaze Production Elsewhere in North America,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Summer 2005): 45–103, available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1KrcZPTVO_Skvtz4zPrAw_wYhSgEsoLDl/view (accessed 5 October 2022).

[65] “Inventory of the Pottery in Salem, 1789-1817,” translated by Frank P. Albright, Lot 48 file, MESDA Research Center, Old Salem Museums & Gardens, Winston-Salem, NC (original inventory at the Moravian Church Archives, Southern Province, Winston-Salem, NC.

[66] Marshall, 2484.

[67] Aufseher Collegium, 3 November 1795.

[68] “Memoir of Peter Oliver, 1810.”

[69] Thacker, “Bill of Sale for Peter Oliver, 1799,” 6 September 1799, in “African-American References Wachovia/Salem NC.”

[70] Able, “How Peter Oliver freed himself”; “Bill of Sale for a Negroe Man Named Peter Oliver,” 15 January 1800, Habeas 1800 F004, LancasterHistory Archives, Lancaster, PA.

[71] “Sworn Statement Signed by Peter Oliver, Habeas Corpus Papers,” 13 June 1800, Habeas 1800 F004, LancasterHistory Archives, Lancaster, PA; Frederick Kuhn, “Order Freeing Peter Oliver, Habeas Corpus Papers,” 13 June 1800, Habeas 1800 F004, LancasterHistory Archives, Lancaster, PA.

[72] Able, “How Peter Oliver freed himself.”

[73] Patricia Galloway, “Material Culture and Text: Exploring the Spaces Within and Between,” Historical Archaeology, Vol. 9, eds. Stephen W. Silliman and Martin Hall (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006), 42–64; John Moreland, Archaeology and Text, in Duckworth Debates in Archaeology (London: Duckworth, 2001).

[74] Aeltesten Conferenz, 23 July 1800.

[75] “Memoir of Peter Oliver, 1810.”

[76] Aeltesten Conferenz, 13 May 1795.

[77] Fries, “Bethabara Diary, 1797,” Vol. 6, 2594.

[78] Aeltesten Conferenz, 27 November 1799.

[79] Ibid, 11 February 1801.

[80] Aufseher Collegium, 21 August 1787.

[81] Aeltesten Conferenz, 13 March 1788; Aufseher Collegium, 29 April 1788 and 6 May 1788.

[82] Fries, “Bethania Diary, 1804,” Vol. 6, 2790.

[83] Historian Nicholas Wood has written about the legal challenges associated with manumitting enslaved persons in North Carolina and the resulting political backlash it could engender. Nicholas P. Wood, “A ‘Class of Citizens’: The Earliest Black Petitioners to Congress and Their Quaker Allies,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 74, No. 1 (2017), 109–144.

[84] Thacker, “Bill of Sale for Oliver, 1786.”

[85] Aeltesten Conferenz, 9 January 1788.

[86] Aufseher Collegium, 22 September 1795.

[87] “Bill of Sale for a Negroe Man Named Peter Oliver,” 15 January 1800.

[88] Aeltesten Conferenz, 23 July 1800.

[89] Aufseher Collegium, 26 January 1801.

[90] Aeltesten Conferenz, 23 September 1801.

[91] Aufseher Collegium, 28 July 1801; Aeltesten Conferenz, 25 January 1802.

[92] Aeltesten Conferenz, 25 January 1802.

[93] Fries, “Salem Diary, 1802,” Vol. 6, 2695; “Memoir of Peter Oliver, 1810.”

[94] “Lease Agreement between Peter Oliver and Samuel Stots,” 17 February 1802, Moravian Church Archives, Southern Province, Winston-Salem, NC. The exact location of Peter Oliver’s farm was established in 2017 by Martha Hartley, Director of Moravian Research at Old Salem Museums & Gardens. Much appreciation is extended to her for sharing this information with the author.

[95] “Memoir of Peter Oliver, 1810.”

[96] Aufseher Collegium, 9 June 1789, 3 November 1789.

[97] Alain C. Outlaw, “Preliminary Excavations at the Mount Shepherd Pottery Site,” The Conference on Historic Site Archaeology Papers, 1974 , Vol. 9, Part 1, ed. Stanley South (Columbia, SC: Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, 1975), 2–12; Outlaw, “The Mount Shepherd Pottery Site, Randolph County, North Carolina”; Whatley, “The Mount Shepherd Pottery: Correlating Archaeology and History.”

[98] Fries, “Friedberg Diary, 1793,” Vol. 6, 2491.

[99] Thomas J. Haupert, “Apprenticeship in the Moravian Settlement of Salem, North Carolina, 1766–86,” Communal Societies, Vol. 9 (1989), 1–9.

[100] Aufseher Collegium, 18 February 1802.

[101] An example of Rudolph Christ’s vigilance regarding potential economic competition was when he complained to the Aufseher Collegium after learning that tobacco pipes made by Bethabara’s potter Gottlob Krause were being sold at Salem’s community store. Aufseher Collegium, 30 September 1794.

[102] Ibid, 31 August 1802.

[103] Aeltesten Conferenz, 28 September 1803.

[104] Aufseher Collegium, 23 July 1805.

[105] “Community Store Letter Book,” 8 November 1806, 12 July 1807, 3 September 1810, Moravian Church Archives, Southern Province, Winston-Salem, NC.

[106] “Probate Records,” 1753–1971, Superior Court, Stokes County, NC; “Bee Gum,” in Appalachian English (Columbia, SC: College of Arts and Sciences, University of South Carolina), online: http://artsandsciences.sc.edu/appalachianenglish/node/329 (accessed 5 October 2022).

[107] “Memoir of Peter Oliver, 1810.”

[108] Ibid.

[109] Aufseher Collegium, 10 October 1810, 27 December 1810.

[110] Ibid, 8 and 23 January 1811, 19 and 24 February 1811, 5 March 1811, 3 March 1812.

[111] Sensbach, “African-Americans in Salem,” 37.

[112] Abel, “How Peter Oliver Freed Himself.”

© 2022 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts