American museums and private collectors have been acquiring paintings by Frederick Kemmelmeyer for nearly seventy years, and his works have been reproduced in books and articles—yet the man behind the brush has proven elusive to researchers. This research note presents recently uncovered information that is hoped will aid future scholars in advancing our understanding of Frederick Kemmelmeyer’s life and career.

One of the first scholars to pursue a comprehensive study of Frederick Kemmelmeyer (b.1752–1753–d.1820–1825) was E. Bryding Adams in her January 1984 article for The Magazine ANTIQUES titled “Frederick Kemmelmeyer, Maryland Itinerant Artist.”[1] At the time she wrote her article, Adams was able to assemble eighteen signed or attributed works and one engraving ascribed to Kemmelmeyer. Since then, curators and scholars have aided in the discovery and/or attribution of more Kemmelmeyer paintings, as well as contributing to our knowledge of the artist’s life, most notably Carolyn Weekley at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in her book and exhibition, Painters and Paintings in the Early American South.[2]

Arrival in America (1782–1788)

Primary among the unanswered questions about Kemmelmeyer are when and why he came to America. The earliest documentation firmly identifying Frederick Kemmelmeyer as an artist is found in a 1788 Baltimore newspaper advertisement. In her book, Carolyn Weekley suggests that Kemmelmeyer was in Charleston, South Carolina, as early as 1783, citing the marriage record of “John Frederick Christian Kemmelmeyer, doctor, born in the Duchy of Wirttemburg [sic]” and “Maria, widow of Christian Gruber, deceased,” at Charleston’s St. John’s Lutheran Church.[3] MESDA had recorded this marriage record in its Craftsman Database and the citation has been a source of discussion among scholars for many years.[4] The reason for the debate is that no link between the John Frederick Christian Kemmelmeyer in Charleston and the Baltimore artist Kemmelmeyer could be made to establish them as the same man. A listing of Hessian troops fighting for Britain in America and an 1812 Philadelphia newspaper announcement may provide the elusive connection between the two men.

It is likely that Frederick Kemmelmeyer was in Charleston at least four months earlier than the St. John’s marriage record announcement—and he could have been in America as early as 1776. Muster roles list a Friedrich Kimmelmeyer serving as a doctor (or related medical position) among the Hessian troops fighting for Britain in America.[5] [6] He served as a Feldscher (assistant medical officer), in the Rall Regiment, the unit that was surprised by General George Washington’s 1776 Christmas attack after crossing the Delaware River near Trenton, New Jersey.[7] It is not known if Friedrich Kimmelmeyer was with the regiment in New Jersey but we do know that he deserted to the enemy in October 1782 in Charleston.[8] Four months later, John Frederick Christian Kemmelmeyer married Maria Gruber at St. John’s Lutheran Church in Charleston.[9] Kemmelmeyer’s decision to join the congregation at St. John’s Lutheran Church seems logical: in addition to being the largest German-speaking church congregation in Charleston, the St. John’s governing body answered directly to the Ducal Consistory of Württemberg in Kemmelmyer’s hometown of Stuttgart and much of the congregation were émigrés from Württemberg.[10]

Kemmelmeyer’s marriage to Maria Gruber may have been prompted by the birth of an illegitimate child. Carolyn Weekley cites a child born in Charleston on 2 October 1782 named Anna Rosina Maria Kemmelmeyer—this is exactly the same month that Kemmelmeyer is recorded as deserting the Hessian regiment.[11] As Weekley suggests, the child may have been fathered by Maria Gruber’s late husband, but Anna Rosina Maria’s birth and the Kemmelmeyer’s desertion occurring at the same time create an interesting coincidence.

Regardless, the marriage between Kemmelmeyer and Gruber was short lived. In a July 1783 edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, the couple informed the public that, “they have this day by mutual consent agreed to for ever separate as MAN and WIFE; and for that purpose have entered into articles of separation.”[12] Their divorce seems to have been a messy one. Barely a year later, a George Warner claimed in the same newspaper that “I never to my knowledge, directly or indirectly, said any thing prejudicial whatsoever to the Character of Mary Kemmelmire, and that I never had any carnal communication with her”—conceivably an indication of infidelity on her part.[13] Public opinion about Kemmelmeyer’s marriage and divorce may have been his motivation for a move to Baltimore, Maryland, between 1784 and 1788.

A Philadelphia newspaper announcement printed nearly thirty years after the Kemmelmeyer-Gruber marriage—at time when the artist Kemmelmeyer was no longer working in Baltimore but traveling as itinerant painter in Western Maryland and Virginia—may provide further support for a connection between the Kemmelmeyer in Charleston and the painter in Baltimore. In June 1812, a Philadelphia newspaper reprinted an article from Winchester announcing the engagement of Kemmelmeyer’s presumed daughter, Francis, to a Peter Klipstine: “John Heiskell, in his Winchester Gazette, says, that Peter Klipstine, printer, is dove-tailed, to Francis Kemmelmeyer, of that borough.[14] Little else is known about Francis Kemmelmeyer. She may have been born during Kemmelmeyer’s marriage to Maria Gruber in Charleston, but it seems more likely that Kemmelmeyer remarried at some point after moving to Baltimore.[15] Peter Klipstine and Francis Kemmelmeyer were wed sometime after the article appeared in the Philadelphia newspaper. According to the recollections of a nineteenth-century Winchester resident: “Peter married a daughter of an old Prussian gentleman by the name of Kimamier.”[16] The couple later appeared in the 1850 Frederick County, Virginia census, along with six children.[17]

Peter Klipstine’s father, Philip Klipstein, provides the link between the Hessian Kemmelmeyer in Charleston and the artist in Baltimore. Philip Klipstein, served as a surgeon’s mate in a Hessian regiment during the Revolution, as did Frederick Kemmelmeyer, although in a different regiment. Both men chose to settle in America following the war.[18] After relocating to Winchester, Klipstein put his talents to use for the local population: “Philip Klipstein of Winchester, former surgeon of the Hessian troops, was perhaps the first regularly trained physician.”[19]

It is hardly unexpected that Kemmelmeyer, the “old Prussian,” would have established or possibly kept up a friendship with Philip Klipstein, a fellow German comrade-in-arms and doctor who shared similar life experiences and heritage. This relationship inexorably would have brought their two families together with the result of Klipstein’s son marrying Kemmelmeyer’s daughter. Further research to more fully understand the Kemmelmeyer-Klipstein relationship from 1783 to 1812 is certainly warranted.

Baltimore (1788–1803)

Frederick Kemmelmeyer advertised that he was an artist for the first time in a Baltimore newspaper.[20] It is not known how long he had been in Baltimore or where he was living. He announced that he had “opened a DRAWING-SCHOOL for young Gentlemen, at his house, next door to Doctor Lemmon’s in Holliday-street.”[21] There are no works attributed to Kemmelmeyer before he was living in Baltimore, but he may have completed as-of-yet unidentified paintings before moving to Maryland. What he was doing during the time between 1783 (after the divorce in Charleston) and his advertisement in Baltimore five years later is still unknown.

Many of the paintings Kemmelmeyer completed between 1788 and 1800, when he was living in Baltimore, directly reflect the culture of his native Europe. Those paintings were inspired by—or in some cases directly copied from—published European print sources.

One of the first paintings of note attributed to Kemmelmeyer is Frederick II Reviewing the Troops at Potsdam (Figure 1). “Frederick II” was better known as Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, and the painting depicts him reviewing his assembled army at Potsdam, just outside of Berlin. The composition of the painting was inspired by a 1777 print engraved after Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki’s (1726–1801) König Friedrichs II. Wachtparade in Potsdam (Figure 2). Frederick the Great was revered by German Protestants and was easily the most famous German military figure of his time. The subject of Frederick II Reviewing the Troops at Potsdam reflects Kemmelmeyer’s German Protestant roots. As already noted, he was a member of St. John’s Lutheran Church in Charleston. In addition, in 1807 he sponsored a newly baptized child at Zion Evangelical Lutheran and Reformed Church in Hagerstown, Maryland.[22] Kemmelmeyer naturally found such an illustrious German religious and military icon a fitting subject for painting, and probably had no trouble finding a customer for the painting among Baltimore’s German-American community.[23]

Another example of Kemmelmeyer’s Baltimore work, one that draws on a stylistic convention found in at least one contemporary German print, is a 1796 certificate of membership for the Charitable Marine Society of Baltimore (Figure 3). Kemmelmeyer drew the design for the certificate, which was in turn engraved by the Baltimore silversmith John Houlton (w. 1794–1804).[24] The scroll at the top of the certificate seems to have been taken directly from a similar one seen on a late-eighteenth or early-nineteenth-century German engraving illustrating a Bohemian battle during the Seven Years’ War (Figure 4 and Figure 5).[25] Whether this scroll motif is specifically German in origin or more likely a broader European device copied and repeated among a number of engravers is open for conjecture.

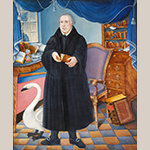

Sometime before the turn of the nineteenth century, he is attributed to have painted a portrait of Martin Luther (Figure 6) that is now in the Corcoran Gallery of Art Collection. Although Kemmelmeyer updated the furnishings in the painting to reflect the incoming Federal style, the painting is clearly derived from a seventeenth-century engraving by the Dutch artist Cornelius Visscher (1629–1658) (Figure 7), which in turn was copied by Allan Ramsey (1713-1784) and engraved by an unknown artist in the late eighteenth century (Figure 8).[26] Kemmelmeyer may have seen either of those prints in Baltimore from which to base his painting. The large scale of Kemmelmeyer’s portrait of Martin Luther—much too large to display in most private homes—suggests that a Lutheran congregation in Baltimore may have commissioned it. Supporting an ecclesiastical commission, a large portrait of Martin Luther with a swan was depicted by Lewis Miller in his 1800 sketch of the interior of Christ Lutheran Church in York, Pennsylvania.[27]

Kemmelmeyer’s only other overtly religious painting is much more difficult to interpret and does not outwardly reflect his Germanic heritage. The Bloody Sentence of the Jews Against Jesus Christ the Lord and Saviour of the World (Figure 9), signed “Baltimore/Painted By/F. Kemmelmeyer,” presents the trial of Jesus Christ by the Jewish Sanhedrin council and Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea. Christ sits forlornly on a block in the foreground. The members of the Sanhedrin council surround him, their names and decisions inscribed on the tablets they each hold. Caiaphas, the High Priest, stands in the middle upon a pedestal, making a decree. Pontius Pilate is seated on the far right, overseeing the trial. At a table in front of Pilate, two scribes are seated, recording the proceedings. The scene that Kemmelmeyer painted is not biblically accurate: all four gospels record that Christ was interviewed by both the Sanhedrin and Pilate, but not at the same time.

The iconography of The Bloody Sentence is derived from a centuries-long debate among religious scholars to determine whether Pontius Pilate or the Jewish council of priests were responsible for sentencing Christ to death.[28] That debate is centered on three apocryphal documents: The Gospel of Nicodemus (also known as The Acts of Pontius Pilate), the Death Warrant of Jesus, and the Protocol of the Sanhedrin.[29] The controversy over who sentenced Jesus had entered popular culture by the late sixteenth century when German broadsheets depicting the event were available as early as 1581. About 1590 a Dutch engraver, Maerten de Voss, also produced a rendition of the story—a print that would be copied throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[30]

Unlike most of Kemmelmeyer’s other historical paintings, The Bloody Sentence contains physical evidence that points directly to the engraved print the artist used as inspiration. A paper legend at the bottom of the painting consists of an English translation of a document titled “The Sentence of Pontius Pilate.”[31] Over the past twenty years, scholars have searched fruitlessly to identify the source of the legend. That mystery has now been solved. The paper legend—and Kemmelmeyer’s design source for the painting—was most likely taken from a print published by John Bowles of London in 1728 (Figure 10).[32] The paper legend on Kemmelmeyer’s painting was cut from a copy of Bowles’s print, quartered, and then applied to the canvas with varnish.

Kemmelmeyer’s painting shares the identical lengthy title of Bowles’s print, and Kemmelmeyer also copied onto his painting exact wording that is included in the Bowles catalog description—“by Publius Lentulus, in the Reign of Tiberious Caesar.” Many prints on the subject of Christ’s trial were made in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but very few have text descriptions and the Bowles print is the only one known that presented the legend in English.[33] Unfortunately, no known copy of the Bowles print survives, but a contemporary English engraving, published by Cluer Dicey circa 1760–1775, makes for an interesting comparison (Figure 11).[34]

How much The Bloody Sentence reflects Kemmelmeyer’s personal religious views is nearly impossible to determine. Anti-Semitism was not uncommon in Europe; Martin Luther, for whom Kemmelmeyer seems to have had an affinity, published a diatribe titled On the Jews and Their Lies in 1543. That said, The Bloody Sentence could have been commissioned by a Lutheran congregation in Baltimore—like his portrait of Martin Luther—and not reflective at all of Kemmelmeyer’s individual personality. Regardless, of all of Kemmelmeyer’s history paintings, The Bloody Sentence remains the most enigmatic and misunderstood.

Another Baltimore painting by Kemmelmeyer is, ironically, one about which much is known although it has not been seen in over two hundred years. On 4 July 1797, at an Independence Day event celebrating the grand opening of Captain David Porter’s Observatory in Baltimore, Kemmelmeyer debuted a painting of Baron Friedrich Freiherr von der Trenck imprisoned in the castle at Magdeburg in Saxony-Anhalt. A description of the work was published in the Federal Gazette & Baltimore Daily Advertiser:

The representation of baron Trenck, as confined in the dungeon of Magdebourg [sic] 10 years, drawn by Kimmelmeyer, evinced much taste, both in design and execution. Beneath the painting was written the following in large characters: “Be not elated in prosperity, nor cast down in adversity—Behold the effects of monarchy—Be not of party nor the dupe of faction. Let the tragical narration of Trenck be a lesson to the afflicted.—Give hope to the despairing, and fortitude to the wavering—and humanize the hearts of kings.”[35]

Kemmelmeyer painted Baron Friedrich Freiherr von der Trenck specifically to be exhibited at Captain David Porter’s watchtower. Porter served as the supervisor for all naval activities in Baltimore at the end of the eighteenth century and on 10 March 1797 he proposed to the citizens of Baltimore, “to build a Look-out House, and raise a Flag-Staff on Federal Hill, that early information may be obtained of ships and vessels coming up the Bay.”[36] The wooden tower was raised with the help of three hundred subscriptions from Baltimore residents and became an impromptu museum. Kemmelmeyer’s painting may have become a permanent fixture.[37] For Kemmelmeyer, displaying his painting at the tower was free advertising.

Friedrich Freiherr von der Trenck (1726-1794) was a Prussian-born officer accused of spying for the Catholic Austrians during the Second Silesian War (1744-1745). Trenck escaped to Russia for a short time, but was arrested upon returning to Prussia and sentenced to ten years imprisonment in Magdeburg. After his release, Trenck was sent to Paris as an observer of the events of the French Revolution for Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. In France he was once again accused of espionage and was executed by guillotine in 1796.[38]

William Spotswood of Philadelphia printed a translation of Trenck’s memoirs in 1791, one of only a few American printings of the autobiography. The frontispiece of Spotswood’s publication likely served as the template for Kemmelmeyer’s rendition (Figure 12). The writing on the painting below the scene corresponds to passages written by Trenck in his memoir, particularly the final few pages.

The timing of Kemmelmeyer’s unveiling of Baron Friedrich Freiherr von der Trenck is significant on two levels. On one hand, in April 1797, only three months earlier, Napoleon’s forces had launched an invasion of the Germanic states, including Kemmelmeyer’s home in the Rhineland-Palatinate. Although Trenck was Catholic, Kemmelmeyer and other Protestant Germans might have regarded him as a patriotic martyr for their homeland who suffered at the hands of French tyrants. As such, Baron Friedrich Freiherr von der Trenck falls firmly within Kemmelmeyer’s celebration of Teutonic heritage evident in his paintings. Simultaneously, Kemmelmeyer chose to honor Trenck on Independence Day, a holiday when American ideals such as freedom and liberty are celebrated.

The painting of General William Darke attributed to Kemmelmeyer in the MESDA collection (Figure 13) is another example of the artist combining a history painting with a portrait.[39] Darke accompanied General Arthur St. Clair’s 1791 campaign into what is now Ohio during an event known as the Northwest Indian War (Little Turtle’s War).[40] St. Clair’s army was soundly defeated by the Miami Indians at the Battle of the Wabash. Among the casualties was Darke’s youngest son, Captain Joseph Darke, who his father reported “was very dangerously and I expected Mortily wounded.[41] Kemmelmeyer’s likeness depicts William Darke at the time of St. Clair’s defeat. With sword upraised and dirk drawn, the general is poised to lead his men into battle. Linda Crocker Simmons described Darke’s expression as “clouded, perhaps intended by the artist to reflect the memory of defeat and personal loss.”[42] The two opposing armies of the battle can be seen in the background, a common feature in Kemmelmeyer’s military-related paintings.

The Federal City (1803–1805)

In 1803, Kemmelmeyer left his business in Baltimore to settle near the new national capital on the banks of the Potomac River.[43] In June 1803, he was in Alexandria, Virginia, professing that “he has become a resident of this town,” and customers could find him “at Mr. Jacob Shuck’s Duke Street.”[44] By October, Kemmelmeyer had relocated to Georgetown in the District of Columbia, on the northern side of the Potomac.[45]

There exists no documented reason for Kemmelmeyer’s relocation to Alexandria, but the move could have been a calculated decision to capitalize on the public’s increasing demand for likenesses of George Washington, hero of the American Revolution and Father of Our Country. Washington had died four years before, in 1799, and Kemmelmeyer may have believed that a shop selling paintings of Washington in the new federal capital was potentially lucrative. As such, a number of Kemmelmeyer’s paintings finished during his stay near the Federal City are of the famous Virginian—indeed, over his career, Kemmelmeyer would create more paintings of George Washington than of any other individual.[46]

By far Kemmelmeyer’s most well-known painting of George Washington is GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON / Reviewing the Western army at Fort Cumberland the 18;th of Octob;r 1794 (Figure 14).[47] In that painting, signed “F. Kemmelmeyer. Pinxit.,” Washington is pictured astride a white horse, facing a line of soldiers assembled before Fort Cumberland in western Maryland.[48] Kemmelmeyer paid particular attention to uniform details, both on Washington and those of his army. Kemmelmeyer painted the theme several times throughout his career.[49] The series was executed to commemorate Washington’s successful quelling of the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. The significance of the paintings might be more personal. As mentioned earlier, from a business perspective paintings of George Washington must have been a steady source of income for Kemmelmeyer, driven by a nationwide obsession in the early nineteenth century for the president’s likenesses; however, viewed through the artist’s personal identity, Washington at Fort Cumberland might be seen as a signal of Kemmelmeyer’s growing identity as an American citizen. Kemmelmeyer was naturalized at the General Court for the Western Shore of the State of Maryland on 8 October 1788 in Annapolis, under the name Frederick Kimmelmeiger.[50] Becoming a United States citizen was a significant step in Kemmelmeyer assuming an American identity, and it is possible to consider the creation of the first Washington at Fort Cumberland painting in 1794 as a symbolic representation of that process.

Another example of a Kemmelmeyer portrait of George Washington is The American Star, now held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Figure 15), also signed “F. Kemmelmeyer. Pinxit.” The inscription on the monument in the painting reads, “First in War / First in Peace / First in defence / of / our Country,” a reference to the Washington’s eulogy given by General Henry Lee III. The monument and eulogy quote denotes the painting as a memorial portrait, possibly commissioned by a Masonic Guild because the symbols surrounding Washington’s image celebrate his status as a soldier, statesman, and Freemason.

Like Kemmelmeyer’s earlier paintings completed in Baltimore, the composition of American Star can be traced to published print sources—this time the artist looked to an American as well as an English print for inspiration. The image of Washington and the bellflowers surrounding it come from a plate in a 1787 edition of The Columbian Magazine, printed in Philadelphia (Figure 16). The design for the military symbols could have come from a 1780 engraving of Washington by William Sharp of London (Figure 17).[51] Also, American Star shares stylistic characteristics with Kemmelmeyer’s earlier Baltimore works. The swag and tassel pattern at the top of the painting relates to the portrait of Martin Luther (see Fig. 6), while the blue and white-tiled floor corresponds to that painted in The Bloody Sentence (see Fig. 9).

An unsigned portrait of Washington attributed to Kemmelmeyer (Figure 18) shares many similarities with the American Star. Once again, a wreath of bellflowers originating from a five-pointed star encases Washington’s image, although in this case the star was inverted. In both paintings, Washington’s likeness was painted over a light-blue background. Washington’s stance in one or both of the paintings could have come from a 1787 engraving by James Trenchard after a portrait painted by Charles Willson Peale (Figure 19).[52]

Kemmelmeyer’s portrayals of Washington are often readily identifiable. At least three of his renderings included Washington encased by the bellflower motif. Washington is most often depicted wearing his Continental Army uniform, which is usually very detailed. In general, every military scene and the uniforms that Kemmelmeyer painted are meticulously detailed, most likely an influence of his service in the Hessian army. The artist usually painted a single button to fasten Washington’s outer coat at mid-chest, revealing his uniform beneath the coat both above and below his chest. Kemmelmeyer’s likenesses of Washington’s face were typically pudgy, with a pronounced chin; his nose elongated and bulbous at the tip. Interestingly, Kemmelmeyer frequently included salmon-colored pockmarks on Washington’s cheeks, vestiges of a bout with smallpox Washington encountered while visiting Barbados in 1751.

It is Kemmelmeyer’s portrait of Charlotte Marsteller, not one of his Washington paintings, that is one of his most successful likenesses and the defining portrait of his career. Charlotte Marsteller (Figure 20), attributed to Kemmelmeyer, was completed circa 1803 while he was still in Alexandria, Virginia.[53] His use of pastel pink and blue hues creates an almost cherub-like quality and seems quite fitting for a child’s portrait. The portrait also reflects Kemmelmeyer’s maturation as an artist. His growing understanding of popular artistic conventions are present, especially those proven popular by his contemporaries. Charlotte holds a basket of cherries in her left hand and on her feet she wears a pair of pink slippers or shoes—composition elements seen in works by Baltimore artist Joshua Johnson, who in turn had learned from the Peales.[54]

Itinerant Artist in Western Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania (1805–1816)

Following his two-year stay around the national capital, Kemmelmeyer took on an itinerant lifestyle that defined the rest of his career. Kemmelmeyer’s travels took him through western Maryland and Virginia and briefly into Pennsylvania. For much of that time, Hagerstown, Maryland, served as a base from which he traveled to other locations.[55] Why Kemmelmeyer left the Washington, DC, area is unknown. It could be that he found fierce competition for commissions in that area and like other artists of the period decided to make a living on the road.[56]

Whatever his reasons for the abrupt change in lifestyle and business, Kemmelmeyer didn’t completely abandon the types of paintings he had become known for in Baltimore and Washington. One of his most accomplished genre paintings depicts Christopher Columbus’s 1492 arrival in the New World (Figure 21). Completed sometime in January 1805 or 1806, the painting includes several elements that appear in Kemmelmeyer’s other genre paintings: a rocky foreground, pastel blue skies, several individuals with similar facial features, detailed backgrounds, and a tree flanking the right-hand side. The subjects and circumstances of the scene were well known: Columbus stands at the forefront of a colorful group of explorers, his left hand gesturing toward the unexplored territory of the New World. Interestingly, Kemmelmeyer’s written description of the scene is inaccurate. Columbus landed on San Salvador Island on 12 October 1492, a day later than Kemmelmeyer wrote in the explanation at the bottom right-hand corner. Little else is known about the painting except that Columbus’s arrival in the Americas may have been a popular subject in the newly established United States at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Regardless, Christopher Columbus is a notable example of a history painting that was probably an outright commission for Kemmelmeyer, a painting with no clear ties to his preferred historical subjects.

He continued to execute genre paintings through the first decade of the nineteenth century, such as Battle of Cowpens (Figure 22), but if the number of surviving portraits is indicative of his output from 1805-1816, then commissions for his likenesses dramatically increased.[57] Kemmelmeyer continued to paint oil portraits as an itinerant portraitist, but they were far outnumbered by the number of pastel drawings he produced from 1805 to 1816. By 1811, Kemmelmeyer was in Libertytown, Frederick County, Maryland, where he painted eight-year-old James McSherry Coale and signed the picture (Figure 23). The portrait of Coale is particularly important because his is the only one of Kemmelmeyer’s sitters for whom another image is known. An engraving of the adult James McSherry Coale appeared in John Livingston’s 1854 book Portraits of Eminent Americans Now Living (Figure 24).[58] [59]

Stylistically, Kemmelmeyer’s portrait of Coale shares several similarities with his painting of Charlotte Marsteller (see Fig. 20). Both Coale and Marsteller were painted with chubby, cherubic faces; wide eyes; stubbed chins; wispy hair; and pale, white skin. Those characteristics occurred in all of Kemmelmeyer’s known portraits of children; indeed, based on physical features alone, Charlotte Marsteller and James McSherry Coale could be mistaken for brother and sister. In both portraits, Kemmelmeyer used pastel blue and pink colors to highlight the sitters’ features. Both subjects were placed in outdoor settings, though Coale’s backdrop was not nearly as finely executed as Charlotte’s. Finally, Kemmelmeyer used similar animals as props—in this case two small, white dogs.[60]

As Kemmelmeyer aged, his ability to paint deteriorated. As early as 1813, some potential clients had come to doubt whether Kemmelmeyer had any future as a painter. John Henkel of Jefferson County, Virginia, reported in a letter that “olde F. Kimelmeire has come to Charlestown and has started at Drawing and Will get a vast of Business if he could do it to perfection[.] But he is getting too old he Cant imitate one in ten[.] the old man Drinks harder Which makes much against him in Drawing.”[61]

Kemmelmeyer’s last signed portrait is indicative of his old age and failing health. On 17 July 1816 he painted Catharina Heiser Weltzheimer (Figure 25), who operated a tavern in Shepherdstown, Virginia.[62] Kemmelmeyer may have painted Catharina’s portrait in exchange for room and board during his stay. It is difficult to judge whether or not Catharina would have been satisfied with the artistic quality of the final product. Parts of Catharina’s body are strangely proportioned. Catharina’s necklace does not sit naturally on her neckline; instead it seems to hover. Her right eye is disproportionate to the rest of her face. Her hands are stiff, and not well defined.

Only eleven portraits that can be firmly attributed to Kemmelmeyer are known—six signed and five attributed. Of those eleven, nine are pastels. What survives is most likely only a fraction of the many “Likenesses as large as life to Miniature, in Oil, Crayons or Water Colours” that Kemmelmeyer produced during his itinerant period.[63] The fragility of pastel portraits may reflect the low number of surviving Kemmelmeyer paintings in that medium; that said, the fact that even nine of Kemmelmeyer’s pastel portraits survive suggests an impressive output as he traveled around the mid-Atlantic region.[64]

Conclusion

Little is known about Kemmelmeyer after 1816. Two months after painting Catharina Heiser Weltzheimer (see Fig. 25), Kemmelmeyer was back in Hagerstown where he “opened a School for Drawing, and Painting in Water Colours… .”[65] Coincidentally, advertisements announcing his opening of drawing schools are both the first and last recording of Kemmelmeyer’s career as an artist.[66] It is possible that his ability to paint had dramatically deteriorated due to age, bad health, and—if John Henkel’s 1813 letter is accurate—heavy drinking. Operating a school for drawing may have been his only option remaining for making a living through his art.[67] Frederick Kemmelmeyer disappears from historic documentation after 1816. He probably died sometime in the 1820s.[68]

Kemmelmeyer left a diverse catalog of work that illustrates the progression of his life and career. He most likely arrived in America as a Hessian medical officer fighting for the British during the War for Independence. His probable association with fellow Hessian surgeon assistant Philip Klipstein and the subsequent marriage of their children is a ripe opportunity for further research, as is a fuller understanding of Kemmelmeyer’s artistic training.

Choosing to stay and make the United States his home, Kemmelmeyer preserved aspects of his German-Protestant identity and painted military and religious subjects from his native land and culture. He based the composition of many of his paintings on published prints that may have been recognizable to his clients. Kemmelmeyer’s capitalization of the nationalism that arose after George Washington’s death is a significant moment in his career. Washington became Kemmelmeyer’s most repeatedly painted subject and those images are particularly important as visual testament of an immigrant’s assimilation into American culture.

When analyzed as a whole, the paintings by Frederick Kemmelmeyer reveal an artist who may not have possessed exceptional talent but one who certainly lived a notable life. The story his paintings tell is of a German immigrant holding onto his heritage, but also of someone who eventually assimilated into an American painter capable of executing historical paintings and portraits “as large as Life… .”[69]

A. Nicholas Powers is a masters degree candidate in the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture through the University of Delaware. He can be contacted at [email protected].[1] E. Bryding Adams, “Frederick Kemmelmeyer, Maryland Itinerant Artist,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, vol. cxxv, no. 1 (January 1984): 284-292. I extend my appreciation and thanks to E. Bryding Adams and Linda Crocker Simmons, curator emeritus of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, for their guidance in my pursuit of Frederick Kemmelmeyer. I also thank Sumpter T. Priddy, III for encouraging my interest in the subject and Gary Albert for editorial guidance in the development of this research note.

[2] Carolyn Weekley, Painters and Paintings in the Early American South (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in association with Yale University Press, 2013), 315-319; exhibition of the same title, 23 March 2013 through 7 September 2014 in the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (online: http://www.colonialwilliamsburg.com/do/art-museums/wallace-museum/painters-paintings/ [accessed 12 September 2013]).

[3] German St. John’s Lutheran Congregation of Charleston, South Carolina, Records, 1763-1787 (translation), 28 February 1783, 28, St. John’s Lutheran Church, Charleston, SC; Lynn Haltiwanger, email message to author, 27 July 2010.

[4] MESDA Craftsman Database, Craftsman ID 64510, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), Winston-Salem, NC.

[5] Inge Auerbach and Otto Fröhlich, Hessische Truppen im amerikanischen Unabhängigkeitskrieg (Hetrina): Index nach Familiennamen, vol. 3 (Marburg, Germany: Marburg Archivschule, 1976), 96.

[6] The Hessian Kimmelmeyer was born in either 1752 or 1753 in the city of Stuttgart, the capital of the Duchy of Württemberg, in what would become Germany (Ibid). His birth date fits the artist: we know Frederick Kemmelmeyer the painter was born before 1755 because he was listed as over forty-five years old in the 1800 Maryland census (Second Census of the United States, 1800 [NARA microfilm publication M32, 52 rolls], Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, National Archives, Washington, DC).

[7] The regiment was renamed the von Trumbach Regiment in 1778, and from 1780 to 1782 it was garrisoned in Charleston. Auerbach and Fröhlich, Hessische Truppen im amerikanischen…, vol. 3, 96.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Discrepancies between the spelling of surnames (i.e., “Kemmelmeyer” and “Kimmelmeir”) and use of variations of proper names (i.e, “Frederick,” “Friedrich,” and “John Frederick Christian”) are common in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century documents. “Germany Names, Personal,” FamilySearch.org, available online: http://familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/Germany_Names,_Personal (accessed 12 September 2013).

[10] The First Consistory Book of the German Evangelical Lutheran Church of St. John’s the Baptist, 1767-1790, 20 July 1787, 57, South Carolina Historical Society, Charleston, SC.

[11] Weekley, Painters and Paintings in the Early American South, 315.

[12] South-Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, Charleston, 26 July 1783: 1-2.

[13] South-Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, Charleston, 26 August 1784: 4-3.

[14] Spirit of the Press, Philadelphia, June 1812: 3.

[15] Kemmelmeyer’s listing in the 1800 Baltimore census lists one boy and one girl under the age of ten, and a woman over the age of forty-five. The girl listed may have been a young Francis. Second Census of the United States, 1800 (NARA microfilm publication M32, 52 rolls), Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, National Archives, Washington, DC.

[16] William Greenway Russell, What I Know About Winchester: Recollections of William Greenway Russell, 1800-1891, edited by Garland R. Quarles and Lewis N. Barton (Staunton, VA: The McClure Publishing Co., 1972), 52.

[17] Seventh Census of the United States, 1850 (NARA microfilm publication M432, 1009 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[18] Philip Klipstein was a native of Gladenbach, a small town in the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, from which the majority of the Hessian troops were recruited. He served in the 3rd Company of the Kassel Light Infantry Regiment, which at some point might have been associated with the Battalion von Linsingen. Auerbach and Fröhlich, Hessische Truppen in amerikanischen…, vol. 3, entry 2697; Entry for Philip Klipstein. Johannes Schwalm Historical Association, Inc. Available online: http://jsha.org/jshacomb.htm (accessed 12 September 2013).

[19] That Philip Klipstein decided to live in Winchester, Virginia, is not surprising. Approximately 3,000 Hessian prisoners were held at Winchester alone from 1777-1783. Lion G. Miles, “The Winchester Hessian Barracks,” Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society Journal 3 (1988): 19-49, 54; Klaus Wust, The Virginia Germans (Charlottesville, VA: The University Press of Virginia, 1969), 87, 184.

[20] How Kemmelmeyer received his artistic training is difficult to ascertain. No paintings attributable to Kemmelmeyer during his time in South Carolina are known, but he likely had at least some artistic training before coming to America. He may have received drawing or sketching training while in the Hessian army; and Kemmelmeyer’s training as a medical officer would have given him intimate knowledge of anatomy, an asset vital to successfully painting portraits and likenesses. Kemmelmeyer’s contemporary, the French miniaturist Philippe Abraham Peticolas (1760–1841), learned miniature painting while serving in the army of the King of Bavaria (Linda Crocker Simmons, “18th and 19th Century Artists Active in the Lower Shenandoah Valley,” Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society Journal 4 [1989]: 91). Another European miniaturist working in America, the Frenchman Joseph-Pierre Picot de Limoëlan de Clorivière (1768–1826), also learned to draw and paint through his military training (Stephen C. Worsley, “Joseph-Pierre Picot de Limoëlan de Clorivière: A Portrait Miniaturist Revisited,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, vol. 28, no. 2 [Winter 2002]: 12. Available online: http://archive.org/details/journalofearlyso2822002muse (accessed 12 September 2013).

[21] The Maryland Gazette, or, the Baltimore Advertiser, 3 June 1788: 3-4.

[22] Frederick S. Weiser, Zion Evangelical & Reformed Church, Hagerstown, 1771-1849 in Maryland German Church Records, vol. 5 (Manchester, MD: Noodle Doosey Press, 1997).

[23] The Moravian artist John Valentine Haidt (1700-1780) is another German-born painter working in America who created religious genre works. Although a generation older than Kemmelmeyer, Haidt’s work within a German Protestant community in America provides obvious parallels to Kemmelmeyer’s career, especially while working in Baltimore. Vernon H. Nelson, John Valentine Haidt: The Life of a Moravian Painter (Bethlehem, PA: Moravian Archives, 2012).

[24] The certificate is inscribed “F. Kemmelmeyer Delin’t/J. Houlton Sculp’t.” The Charitable Marine Society of Baltimore was incorporated in 1796 to support the widows and orphans of deceased sailors. Widows were entitled to benefits for life, while orphans could receive them until the age of ten. John Houlton worked as a silversmith in Baltimore between 1794 and 1801. He had multiple business partners while in Baltimore, including Liberty Browne between 1794 and 1798. Ralph and Terry Kovel, Kovel’s American Silver Marks: 1650 to the Present (New York: Crown Publishers, 1989), 188; John Thomas Scharf, History of Baltimore City and County From the Earliest Period to the Present Day: Including Biographical Sketches of their Representative Men (Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1881), 592.

[25] In spring 1757, Frederick the Great and his allies invaded Bohemia to inflict a decisive blow on the enemy Austrian forces. This scene illustrates a skirmish between the Duke of Bavaria’s forces and those of the Austrians near the village of Busch-Wersdorf, in what is now the Czech Republic. The Austrians were defeated, but not before igniting their remaining powder stores inside a nearby castle. The figure on horseback in the foreground is likely Maximilian III Joseph, Prince-elector of Bavaria (1727-1777). The engraving comprises two sheets, perhaps pages from a folio detailing Seven Years’ War battles. F.W. Longman, Epochs of Modern History: Frederick the Great and the Seven Years War, edited by Edward E. Morris (London: Longmans, Green, and Company, 1881), 106-110.

[26] For the first identification of Visscher’s print as a design source, see Eleanor H. Gustafson, “Museum Accessions,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, vol. cxx, no. 5 (November 1981): 1092.

[27] Lewis Miller: Sketches and Chronicles; The Reflections of a Nineteenth Century Pennsylvania German Folk Artist (York, PA: Historical Society of York County, 1966).

[28] John Dominic Crossan, Who Killed Jesus?: Exposing the Roots of Anti-Semitism in the Gospel Story of the Death of Jesus (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1995).

[29] Edgar J. Godspeed, Famous Biblical Hoaxes (Boston: Beacon Press, 1956).

[30] Correspondence from German woodcut scholar Dr. Christa Pieske of Lubeck, Germany, to Bradford L. Rauschenberg, MESDA’s Director of Research, 1989; cited in Forsyth Alexander, “He Confounds the People,” The Luminary (Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts newsletter), Summer 1989, 4-5. See also a print titled “The Unjust Trial of Chirst” by Abraham Bach (w. 1648–1702 in Augsburg) reproduced in Dorothy Alexander, The German Single-Leaf Woodcut, 1600-1700 (New York: Abaris Books), 38.

[31] For more information about the legendary document “The Sentence of Pontius Pilate,” see Godspeed, Famous Biblical Hoaxes.

[32] John Bowles, A Catalogue of Maps, Prints, Books, and Books of Maps, Which Are Printed for and Sold by John Bowles, at Mercer’s-Hall in Cheapside, London (London, 1728), 8. I thank Daniel Ackermann, MESDA’s associate curator, for bringing this source to my attention.

[33] For examples, see “The Unjust Trial of Chirst” by Abraham Bach (w. 1648–1702 in Augsburg) reproduced in Alexander, The German Single-Leaf Woodcut, 1600-1700, 38; “The Bloody Sentence of the Jews Against Jesus Christ…” by Robert Sayer, 1766 (listed in Scripture Prints from Robert Sayer’s New and Enlarged Catalog); and “The Bloody Sentence of the Jews, or a Perfect List and Effigies of the Persons Who Sat as Judges of Our Savior” by Sayer and Bennet, 1775 (listed in Scripture Prints from Sayer and Bennet’s Enlarged Catalogue of New and Valuable Prints [London: 1775; reprinted by New Holland Press, 1975]).

[34] A copy of Thompson’s print was sold offered for sale on 16 October 2007 by Halloway’s Auctions (Banbury, Oxford, England), lot 58.

[35] Federal Gazette & Baltimore Daily Advertiser, 6 July 1797: 3-5.

[36] Federal Gazette & Baltimore Daily Advertiser, 10 March 1797.

[37] Federal Gazette and Baltimore Daily Advertiser, 29 July 1797; the phrase “transparent painting” could indicate that Kemmelmeyer’s painting of Trenck was on glass. If so, the painting is probably long destroyed. In the late nineteenth century, the site at Federal Hill became a public park owned by the city of Baltimore. In 1888, the city’s park commission built a new, Victorian-style tower with an ice cream stand at its base. The new tower rocked in high winds, and it was toppled in 1902. It was never rebuilt.

[38] Abraham Rees, The Encyclopaedia; or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature, vol. xxxvii (Philadelphia: Samuel F. Bradford and Murray, Fairman and Company, 1805-1821).

[39] Darke was born in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania in 1736. When he was four years old, he moved with his family to near Shepherdstown, Virginia. Darke fought in both the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution, and served as a Virginia delegate to the 1788 Constitutional Convention; he voted to ratify the Constitution.

[40] In the years following the Revolutionary War, Americans poured into the western territories, resulting in hostilities between native peoples and settlers. In 1790, President Washington authorized military intervention to protect settlers on the western frontier. As part of that initiative, Governor Arthur St. Clair led an expedition into Ohio to erect a string of forts stretching from Lake Erie to present-day Cincinnati. On 4 November 1791, a force of Native American warriors led by the Miami chief Little Turtle attacked and successfully defeated St. Clair’s army. “Ohio’s Native American Wars,” Touring Ohio: Adventures, Itineraries & Dramatic History, available online: http://www.touring-ohio.com/history/indian-wars.html (accessed 12 September 2013).

[41] William Darke to George Washington, letter, 9 November 1791. Rediscovering George Washington, “Gilder Lehman Collection Documents.” Online: http://www.pbs.org/georgewashington/collection/pres_1791nov9.html (accessed 12 September 2013).

[42] Linda Crock Simmons, Jacob Frymire: American Limner (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1975), 51.

[43] Though Kemmelmeyer did not move to the Washington, D.C. area until 1803, working dates for many of his Washington paintings stretch from 1800 to about 1803. Kemmelmeyer likely began painting images of Washington as early as 1800, or even before.

[44] Alexandria Advertiser and Commercial Intelligencer, Alexandria, VA, 27 June 1803: 3-4.

[45] Washington Federalist, 21 October 1803: 3-4.

[46] Three signed and four attributed paintings of Washington by Kemmelmeyer survive in public institutions and private collections. Those in public institutions include: The American Star (Metropolitan Museum of Art), Washington Reviewing the Western Army at Fort Cumberland, Maryland (Metropolitan Museum of Art), Gen;l Geo;e Washington (New York Public Library), George Washington (Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts), and GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON/Reviewing the Western army at Fort Cumberland the 18;th of Octob;r 1794 (Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum). Those in private collections include A Portrait of General George Washington Against the Backdrop of a Battle Scene, and a third Whiskey Rebellion scene: Gen;l Geo;e Washington/Reviewing the western army at fort Cumberland Sepemb;r 19th 1794.

[47] It is possible that Winterthur’s Washington at Cumberland painting dates to as early as 1794. Some have suggested that the artist was at the scene; Kemmelmeyer’s portrait of General William Darke (Fig. 13), probably done before Darke’s death in 1801, could indicate that Kemmelmeyer was in the Backcountry much earlier than previously thought. However, Kemmelmeyer painted the Washington at Cumberland theme multiple times throughout his career.

[48] The flock of birds seen flying in the top right hand corner of the Washington at Cumberland painting also appears out of the left-hand side window in Kemmelmeyer’s painting of Martin Luther.

[49] Several of Kemmelmeyer’s Washington at Fort Cumberland paintings could have been made in western Maryland or Virginia because a large part of the militia called out for the Whiskey Rebellion came to permanently settle in those areas.

[50] Adams, “Frederick Kemmelmeyer,” 285.

[51] See “18th century American magazines: one to share…” by Tim Hughes, available online: http://blog.rarenewspapers.com/?p=930 (accessed 12 September 2013) and New York Public Library Digital Gallery image ID 422726, available online: http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/dgkeysearchdetail.cfm?trg=1&strucID=247518&imageID=422726&word=Sharp%252C%20William&s=3¬word=&d=&c=&f=4&k=0&lWord=&lField=&sScope=&sLevel=&sLabel=&total=7&num=0&imgs=20&pNum=&pos=2 (accessed 12 September 2013).

[52] Available online: http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/george-washington-94549 (accessed 12 September 2013).

[53] Charlotte Marsteller is not signed; however, it is possible to link the painting to Kemmelmeyer through another, signed, child’s portrait, James McSherry Coale (Fig. 23). Charlotte Marsteller was the daughter of Philip Godhelp and Christiana Copper Marsteller. Little is known about Charlotte’s long life. She never married, and in her old age lived with her brother Samuel Arell Marsteller at his home, Arellton, near Manassas in Prince William County, Virginia. She died in 1871. Oral tradition for Charlotte’s portrait says that the house in the background of the painting is her brother’s home, Arellton. But since the house was built between 1825–1828, and Charlotte’s portrait dates to no later than 1803, the house in the painting cannot be Arellton. Kemmelmeyer’s contemporary, Jacob Frymire, painted portraits of both Charlotte’s grandparents, Colonel Philip Marsteller and Magdalena Rice Marsteller, and her brother, Samuel Arell Marsteller, in 1800. All are in private collections. See Simmons, Jacob Frymire, 25-27 for more information.

[54] In Johnson’s portrait of Edward and Sarah Rutter at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Edward holds a basket of cherries while Sarah’s hand hovers over it. In addition, Sarah dons a pair of pointed red shoes similar to those Kemmelmeyer painted for Charlotte Marsteller. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, acc. no. 65.254.3, available online: http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/11269?rpp=20&pg=1&ft=Joshua+Johnson&pos=1 (accessed 12 September 2013).

[55] It is not known exactly when Kemmelmeyer left the Georgetown area. He is last documented in that city when he placed an advertisement in the Washington Federalist on 21 October 1803. He did not appear again until he moved to western Maryland and began promoting himself as a portraitist in the 14 June 1805 edition of Bartgis’s Republican Gazette of Frederick, Maryland, and a day later, on 15 June, in the Frederick-Town Herald. Three months later he placed an ad in the 20 September 1805 edition of the Maryland Herald & Hagerstown Weekly Advertiser.

[56] “While some painters lived in cities that were large and wealthy enough to support their careers, or combined portrait painting with different forms of work, others had a more itinerant lifestyle, traveling from town to town in search of commissions… Usually, an artist arriving in town would place an advertisement in the local paper advising the populace of his or her availability to undertake portrait commissions. Frequently, entire members of a family would be painted by an artist during his stay and then he would move on to another town where he would paint a different branch of the family.” From “Early Portraits,” American Folk Art Museum, available online: http://www.folkartmuseum.org/portraits (accessed 12 September 2013).

[57] Other paintings that fit into this style include: Battle of the Boyne (ca. 1788-1800), Battle of Cowpens (1809), General Wayne Obtains a Complete Victory over the Miami Indians (ca. 1794-1821), and View of the Bombardment of Fort McHenry (ca. 1814-1821).

[58] James McSherry Coale was the son of Richard and Catherine McSherry Coale and the family lived at the Coale House built in 1783 in Libertytown at the intersection of Main Street and Walnut Avenue. In 1843, as the elected president of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company, James McSherry Coale renewed the efforts to create a canal from Georgetown to Cumberland, Maryland. Coale died on 22 February 1882, and is buried in the cemetery of St. Peter the Apostle Roman Catholic Church in Libertytown. James McSherry, History of Maryland, edited by Bartlett B. James (Baltimore, MD: The Baltimore Book Company, 1904), 325-326.

[59] The portrait of James McSherry Coale was reproduced in John Livingstone, Portraits of Eminent Americans Now Living: With Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Their Lives and Actions, vol. 3 (New York: The New York Bar, 1854. Available online: http://books.google.com/books?id=mU0-AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA299&dq=portraits+of+Eminent+Americans+Now+Living+%22McSherry+Coale%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=UznfT42rA_G36QG6mtSVCw&ved=0CD8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed 12 September 2013).

[60] The small bird on Coale’s right-hand finger also appears on a pastel of an unidentified girl from Hagerstown, Maryland, circa 1806. Animals as props appear on Kemmelmeyer’s portraits of children far more than on those of adults.

[61] John Henkel to Solomon Henkel, letter, 18 February 1813, Comstock-Miller Henkel Press Collection, Anne P. and Thomas A. Gray Library, Old Salem Museum & Gardens, Winston-Salem, NC.

[62] Catharina Heiser Weltzheimer was born 11 June 1765, the daughter of John Hizer (Heiser). She married Frederick Weltzheimer on 6 July 1793 in Berkeley County, Virginia. In 1808, she acquired an “ordinary” license to open a tavern on Princess Street in Shepherdstown. She died at the age of 58 years on 23 September 1823 and is buried in Shepherdstown. Both the Weltzheimer Tavern and an early nineteenth-century building known as the Weltzheimer house still stand in Shepherdstown. The latter is on the property of Shepherd University and is undergoing restoration with university’s help.

[63] Maryland Herald and Hagerstown Weekly Advertiser, 13 November 1816: 3-5.

[64] “The Eighteenth-Century Pastel Portrait,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, available online: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/papo/hd_papo.htm (accessed 12 September 2013).

[65] Maryland Herald and Hagerstown Weekly Advertiser, 13 November 1816: 3-5.

[66] In addition to Baltimore and Hagerstown, Kemmelmeyer advertised that he taught drawing in Alexandria, Georgetown, and Chambersburg (Pennsylvania). Alexandria Advertiser and Commercial Intelligencer, Alexandria, VA, 5 September 1803; Washington Federalist, Georgetown, DC, 21 October 1803; and Franklin Repository, Chambersburg, PA, 25 November 1806.

[67] He would have been sixty-four years old in 1816. John Henkel to Solomon Henkel, letter, 18 February 1813, Comstock-Miller Henkel Press Collection, Anne P. and Thomas A. Gray Library, Old Salem Museum & Gardens, Winston-Salem, NC.

[68] Kemmelmeyer does not appear in a search of the 1830 federal census. Census of the United States, 1830. Records of the Bureau of the Census, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[69] Franklin Repository, Chambersburg, PA, 25 November 1806.

© 2013 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts

![Fig. 21: “First Landing of/CR. Columbus at the/Island of St. Salvador South/America the 11th October” by Frederick Kemmelmeyer (w.1788-1816); circa 1805-1806. Signed “Kemmelmeyer Pinxit the [illegible] January 180[5 or 6].” Oil on canvas; HOA: 27-5/8”, WOA: 36-7/16”. Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, acc. no. 1966.13.3.](https://www.mesdajournal.org/files/Powers-Fig-21-Thumb.jpg)