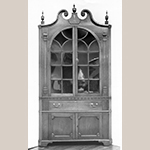

In the fall of 1973 MESDA’s founder Frank Horton and curator Carolyn J. Weekley organized the museum’s first major exhibition with an accompanying catalog, The Swisegood School of Cabinetmaking (Figure 1). MESDA had opened to the public only eight years prior, in 1965, the same year that a neoclassical desk signed by the cabinetmaker John Swisegood came to the museum’s attention. Horton and MESDA curators researched the desk and by the time of the exhibition had discovered approximately forty examples of Swisegood-related furniture made in northern Davidson County, North Carolina (Figure 2), twenty of which were exhibited in the show (Figure 3).[1] By 1973, MESDA had also identified four cabinetmakers in the group: Mordecai Collins (1785–1864), his apprentice John Swisegood (1796–1874), Swisegood’s apprentice Jonathan Long (1803–1858), and lastly Jesse Clodfelter (1804–1870).[2]

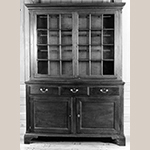

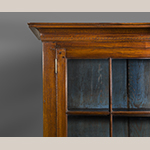

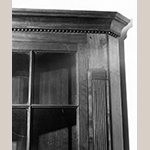

No signed examples of Mordecai Collins’s work were known in 1973. Because “the construction of some [pieces in the group] was heavier, of lesser quality, and with wrought nail construction,” compared to the finer, neater, cut nail construction of the signed John Swisegood examples, MESDA’s curatorial team assumed that Swisegood’s teacher, Mordecai Collins, must have made the “lesser quality” pieces.[3] In addition, the examples presumed to be made by Collins “consist[ed] of only one form, the corner cupboard,” and the example illustrated in Figure 4 was considered his earliest surviving work because of its ogee bracket feet, tombstone-shaped upper door, baroque pediment, and heavy urn-shaped finials.[4]

In the forty plus years since the Swisegood exhibition and catalog, three examples of signed Mordecai Collins furniture have surfaced (to be discussed later and illustrated in Fig. 34, Fig. 40, and Fig. 49). Surprisingly all three are much more akin to John Swisegood’s neoclassical work than to the earlier corner cupboard originally attributed to Collins (Fig. 4). Because the three signed Collins pieces are so unlike the earlier cupboard, they necessitated a re-evaluation of the Swisegood school of cabinetmaking.

Furthermore, documentary evidence sheds new light on the group’s history. Although MESDA’s initial determination that Mordecai Collins, John Swisegood, Jonathan Long, and Jesse Clodfelter were the primary makers of these pieces is still accurate, their story is much more complex than previously known. In fact, evidence suggests that previously unidentified cabinetmakers were also working within the school. The purpose of this article is to present new findings related to the Swisegood school of cabinetmaking that provide a fuller, more accurate history of one of Piedmont North Carolina’s largest and most important furniture groups.

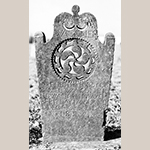

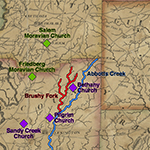

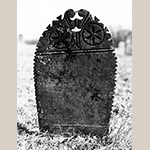

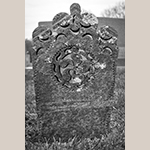

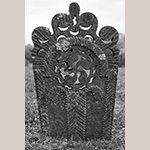

If Mordecai Collins was not responsible for the corner cupboard illustrated in Fig. 4, who was? Who originated the characteristics that ultimately came to be easily recognized as Swisegood style? The answer appears to lie where the school was previously thought to have ended—with the Clodfelter family of northern Davidson County. Four years after MESDA’s “Swisegood School of Cabinetmaking” exhibition closed, MESDA’s director of research, Bradford Rauschenberg, wrote an article in which he related carved baroque-style decoration found on numerous gravestones in Davidson County (Figure 5 and Figure 6) to decoration found on corner cupboards from the Swisegood school. In the article he establishes that:

the furniture of the Swisegood school… best represented for our purposes [of comparison is] a corner cupboard [Fig. 4] attributed to Collins… . The details and moldings of this particular cupboard best compare with the baroque-style gravestones.[5]

Rauschenberg notes, however, “that research [had] not located a single stone that was signed.”

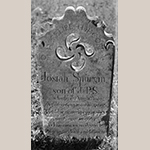

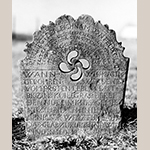

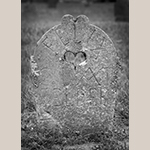

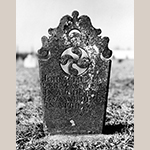

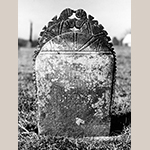

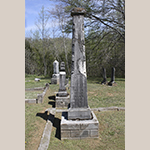

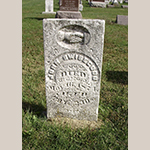

Since Rauschenberg’s 1977 article, one stone with a signature has been identified and is discussed in Ruth Little’s well-researched 1998 publication Sticks and Stones: Three Centuries of North Carolina Gravemarkers. Little documents the back of a stone marking the grave of six-year-old Josiah Spurgeon with the inscription “MAID BY THE HAND OF JOSEPH CLODFELTER” (Figure 7 and Figure 8).[6] She introduces the life and work of gravestone carver Joseph Clodfelter (1801–1872), noting that he did at least basic woodworking in addition to stone carving because the 1850 Davidson County estate records for Sara Snider include a $9.00 payment to him for two coffins.[7]

Most germane to the Swisegood school of cabinetmaking is Ruth Little’s hypothesis that Joseph Clodfelter’s father, Jacob Clodfelter (1770–1837), was also a gravestone carver and woodworker.[8] It is this author’s conclusion that Little’s hypothesis is correct and that the corner cupboard illustrated in Fig. 4 was made by Jacob Clodfelter. Such an attribution explains the obvious similarities between the decoration found on the corner cupboard and that on the Joseph Clodfelter pierced gravestones—most notably the scrolled pediment with finials and various molded elements. Furthermore, a closer look at the original Clodfelter family that migrated to northern Davidson County connects four generations of the family with each of the subsequent men identified as members of the Swisegood school of cabinetmaking.

Felix Clodfelter and His Family Settle on the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek

The earliest known Clodfelter to arrive in Davidson County was Felix Clodfelter (also spelled “Glattfelder” or “Glattfelter”). He was born in Glattfelden, Switzerland, near Zurich, in 1727 and lived there with his family until the summer of 1743, when he, his mother, and five brothers and sisters made the treacherous journey to Philadelphia, arriving on 30 August aboard the Francis and Elizabeth. His father had died the previous year, but his father’s brother, Casper Clodfelter, led the traveling band of sixteen family members to Pennsylvania, presumably in search of new opportunity.[9]

Most of the Clodfelters settled in York County, Pennsylvania along the south bank of Codorus Creek. In 1750, twenty-three-year-old Felix Clodfelter married Sarah Meyer, and their marriage was recorded at Christ Lutheran Church in York (Figure 9).[10] Their oldest son, John Clodfelter (1751–1826), was christened at Christ Lutheran Church.[11] Five of their other children were also born in York County, including a second son Peter (1763–1843). Unexpectedly, there is no evidence that Felix Clodfelter ever owned property in Pennsylvania.[12] How he supported his young family is unknown, but perhaps he worked with the patriarch of his family, Uncle Casper Clodfelter, a farmer who, according to family history, “was also something of a carpenter or cabinetmaker, since in 1767 he made the coffin for Peter Ness,” the husband of a niece.[13]

In 1763 Felix Clodfelter and his family followed in the footsteps of thousands of Pennsylvanians down Virginia’s Great Wagon Road into Piedmont North Carolina. The Clodfelters quickly joined a close-knit immigrant community in Davidson County, comprised of families such as the Byerleys, Delaps, Longs, Swisegoods, and Waggoners. On 19 August 1763, “Faelick Scloffelder” purchased his first piece of property from Frederick and Christian Michal for £50, described as “230 A on Brushy Fork of Abbotts Crk. adj. Jacob Waggoner” (Figure 10).[14] In 1769 he purchased an additional 101 acres “on Brushy Fork of Abbotts Crk.”[15] One year later, in 1770, his youngest son Jacob Clodfelter was born, the only son to be born in North Carolina.[16] [17]

In December 1791 Felix Clodfelter gifted a large portion of his property, “for love, good will, and affection,” to three of his sons. The oldest son, John Clodfelter, was given the northern “part of the homestead”; middle son, Peter Clodfelter, the southern part; and the youngest, Jacob Clodfelter, the middle part.[18] In 1809, at age eighty-two, Felix Clodfelter made his will, leaving his wife Sarah “full possession of the house I now live in during her lifetime,” along with all the necessities required to live comfortably for the remainder of her life, including “her chest, her bed and bedstead and furniture, and all the linen she now has in possession… also the corner cupboard containing all within it… and [a] little walnut table.”[19] Felix Clodfelter died on 18 January 1814, outliving his wife by two months, she having died 23 November 1813.[20]

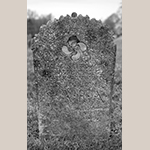

The couple’s standing in the small community is hinted at by an entry in the Friedberg Diary, a record kept by the Moravian minister at Friedberg Moravian Church, located approximately ten miles northwest of the Clodfelter homestead: “Jan. 20, 1814—The funeral sermon of Felix Gladtfelder [Clodfelter] was preached in the Zion Church [Bethany Church at Opossumtown], to a large gathering.”[21] Felix and Sarah Clodfelter were buried in Bethany Church Graveyard near the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek. Decorative gravestones mark their graves (Figures 11 through 14), probably carved by the couple’s youngest son, Jacob Clodfelter, father of the self-proclaimed pierced gravestone maker Joseph Clodfelter.[22]

The three sons of Felix Clodfelter must have been intimately involved in one another’s lives. John, Peter, and Jacob Clodfelter lived on and farmed contiguous pieces of property given to them by their father; they all attended Bethany Church and were buried in its graveyard (Figures 15 through 19); and their wills and estate sales suggest that although they were farmers, they all practiced some degree of woodworking as well. In this respect they were not unlike their great uncle Casper Clodfelter, the head of the clan in America, and probably not unlike their father as well.

John Clodfelter was the first brother to die, on 24 April 1826, and at his 14 July estate sale the following items related to woodworking were sold:

|

|

Peter Clodfelter was the last brother to die, on 4 October 1843. His 22–23 November estate sale also included woodworking-related items:

|

|

In addition, a wide variety of furniture forms were sold from Peter Clodfelter’s estate:

|

|

The estate records of John and Peter Clodfelter indicate that although they were primarily farmers, carpentry was a skill with which they were both familiar.

It was the youngest brother, Jacob Clodfelter, however, whose estate inventory and sale leave little doubt that he had been heavily involved in woodworking. He died on 1 February 1837, and his estate inventory included over 10,000 feet of plank and scantling (at least 700 feet of walnut plank) and the following items:

|

|

This extensive inventory establishes that Jacob Clodfelter was making barrels, creating gunstocks, building structures, fashioning furniture, and—as Ruth Little hypothesizes—carving gravestones. One of the purchasers at Jacob Clodfelter’s sale was an identified Swisegood school cabinetmaker, Jonathan Long, then age thirty-three, who purchased the turning chisels and all of the walnut plank.[27]

According to Brian Coe, who served as the master cabinetmaker of the Single Brothers’ Joinery Workshop at Old Salem Museums & Gardens, the corner cupboard illustrated in Fig. 4 could assuredly have been made with the tools listed in Jacob Clodfelter’s estate inventory.[28] The corner cupboard was completed circa 1795, which fits neatly into Jacob Clodfelter’s working dates.[29] The direct relationship between the corner cupboard design elements and those found on the pierced stones, as noted by Rauschenberg and Little, strongly argues that both types of objects—those of wood and those of stone—came from the same shop. Thus, Jacob Clodfelter, not Mordecai Collins, appears to be the craftsman who originated the stylistic and construction characteristics of cupboards that have defined the Swisegood school style for over forty years.

The corner cupboard characteristics of the Swisegood group, as exhibited on the Jacob Clodfelter example (Fig. 4), include:

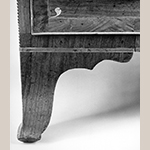

• the pattern of the applied bracket foot, in this instance slightly ogee shaped (Figure 20)

• flat lower door panels outlined with applied molding, here lunetted (Figure 20)

• drawer fronts with molded edges, here beveled but in later examples scratch beaded or cockbeaded (Figure 20)

• chamfered corners that terminate in lambs’ tongues (Figure 20)

• rope-carved applied corner inserts (Figure 21)

• side panels flanking the upper door, here topped with reeded and fluted swelled, “mushroom-shaped” caps (Figure 21), but later caps are flat, rectangular examples

• arched-head upper door (this is the only known instance of a tombstone shape) (Figure 21)

• upper shelves with concave, double-beaded fronts and deep plate grooves (Figure 22)

• a scrolled pediment terminating in applied rosettes, here with a central eye (Figure 23)

• urn-shaped finials with the central finial positioned above a fan-shaped plinth (Figure 23)

Jacob Clodfelter’s corner cupboard also illustrates one construction characteristic unique to and consistent within the Swisegood school—kerfed and bent drawer sides that enclose a thick drawer bottom with “double indented groove[s],” that, in turn, slide over “two tracks on the cupboard dust divider” (Figure 24; see also Fig. 98 and Fig. 99).[30] The drawer dovetails on this cupboard are wide and wedged (Figure 25), the nails are wrought, and Jacob Clodfelter used walnut as a secondary wood along with yellow pine—all characteristics of the earliest examples of Swisegood school furniture. Overall, the corner cupboard illustrated in Fig. 4 is not inspired by the lighter lines of neoclassicism; it is firmly planted in the baroque realm. One has to wonder if the “corner cupboard containing all within it” that patriarch Felix Clodfelter left to his wife Sarah in his 1809 will was similar to the corner cupboard illustrated in Fig. 4, or possibly the very same cupboard.[31]

Only one other example of extant Swisegood school furniture has the same early characteristics found on the corner cupboard. The cupboard illustrated in Figure 26 is a form colloquially known today as a “step-back” but was identified in Peter Clodfelter’s estate sale as a “side cupboard.” As with his corner cupboard (Fig. 4), Jacob Clodfelter’s side cupboard appears to be the prototype for all side cupboards in the Swisegood school.[32] He made it with a separate upper and lower case. The upper case has no bottom board but each side of the top forms two tenons that fit into two corresponding mortices on the top of the cupboard base. A piece of molding attached to the top of the base hides the joint and helps secure the upper case (see Fig. 74, Fig. 75, and Fig. 76 for identical construction).

The simple foot shape echoes that on the corner cupboard in Fig. 4 but is straight, not ogee. The lower doors have beveled edges and flat panels with applied molding, but no lunetted corners; the three drawer fronts also have beveled edges (Figure 27). An applied molding decorates the top edge of the cupboard base. The drawer fronts are attached to the drawer sides with large wedged dovetails, very similar to those on the corner cupboard drawer. The upper case of the cupboard contains three shelves, and the top of the cupboard base acts as the fourth; this cupboard also has three plate rails, all double beaded. The cornice molding is composed of three pieces: the lower one is a rounded carved element, the second has an ogee shape with an upper fillet, and the top is a flat piece with a curved edge.

The base of the side cupboard has chamfered corners terminating in lambs’ tongues, while the upper case has chamfered and reeded corners, also terminating in lambs’ tongues. As he did on the corner cupboard in Fig. 4, Jacob Clodfelter used both walnut and yellow pine as secondary woods on the side cupboard, as well as wrought nails. This cupboard has no known provenance but was purchased less than ten miles from the area where the Clodfelter family had settled and lived on the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek.[33]

Jacob Clodfelter died a wealthy man, leaving his sons land and all of his children over $1500 from his estate sale, as well as fourteen slaves.[34] Based on the items listed in his extensive estate inventory, he was involved in a variety of enterprises, and his slaves probably participated in all of them. Jacob Clodfelter may not have spent much time woodworking during the latter part of his life. Still, he appears to have originated a furniture style that his neighbors liked, and his personal success as a businessman and farmer cannot be questioned. Ultimately, he left his children with the resources that contributed to the legacy of the Clodfelter family of Davidson County.

The documentary evidence and three signed examples of Mordecai Collins furniture that have come to light since the 1973 MESDA exhibition, along with the discovery of a signed pierced gravestone, allow us to tell a different and more expansive story about the Swisegood school than the one previously thought to be correct. It is now possible to attribute the early cupboards (Fig. 4 and Fig. 26) to the hand of Jacob Clodfelter and to understand that his work serves as the prototype for all other cupboards in the group.

Mordecai Collins Brings Neoclassicism to the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek

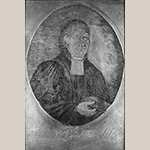

Mordecai Collins’s entrance onto the Davidson County cabinetmaking stage begins with Reverend Paul Henkel (1754–1825), the well-known minister who spent much of his life establishing and supporting German Lutheran churches throughout the South, especially the Backcountry regions of Virginia and North and South Carolina.[35] Henkel’s missionary calling resulted in his bringing his wife, six children, and two cows from their relatively comfortable home in the town of New Market, Virginia to “the woods” of Piedmont North Carolina in the summer of 1800 (Figures 28 and 29).[36] There Rev. Henkel hoped to minister to the rural residents and bring “salvation [to] their souls.”[37] His congregations included Pilgrim Church, sometimes called “my first church” by Henkel, and Bethany Church, called “Zion Church in Opossumtown” by the Moravians.[38]

Bethany was the home church of the early Clodfelters, and many members of the family were buried there (see Figs. 11 through 19). Bethany Church is approximately ten miles from Pilgrim Church in northeastern Davidson County (see Fig. 10).[39] Prior to Rev. Henkel’s arrival, one of his congregants, Elder Adam Harman, purchased a small farm for him on the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek, where the Henkel family lived for the next five years prior to their return to New Market in July 1805.[40] The oldest Henkel son, Solomon (1777–1847), a well-respected physician and businessman in New Market, stayed behind, as did, initially, his younger sister Naomi (1782–1848) and her new husband, Henry Rupert (1774–ca. 1837).[41] Thanks to numerous surviving letters between Solomon Henkel and his family members “in the woods” of North Carolina, we learn of Mordecai Collins’s entry into northern Davidson County.

Rev. Henkel wrote in his Autobiography that, “In June [1802] my son-in-law, Henry Rupert, arrived in our home with his small family.”[42] Apparently a few months later Rupert went back to New Market and then returned to Davidson County with a newcomer. On 9 November 1802 Rupert wrote to Solomon from Davidson County:

I and Mordeka arrived on the 13th of October and found them all well… . I am still living with the old people [Rev. and Mrs. Henkel], and I have the intention to live here until spring. Father got a school house from the Parish. The Parish built the school house many years ago… and they never held any school in the same, then father asked for it, and they granted him the house, and that is to give now a kitchen for mother, and also a shop for me, where I can work this winter… . I believe there is more work than I and Mordeka will be able to do. For this short time I have already 7 families for whom I have to work, and another man who lives 20 miles from here sent to ask me if I am going to do the carpenter work for a house for him during this winter. Tomorrow we have the intention to go to Guilford County to do some joiner’s work for Philip [Rev. Henkel’s second son, also a minister, who had married Henry Rupert’s sister Catherine]… . Naemy [Naomi] was at Francis Ries’ friend Miller at Salisbury… . Miller would like us very much to move there too in order to have a neighbor, for he thinks Salisbury a good place for my trade and there are no joiners living in that city, only a drunken one who is not much good for anything.[43]

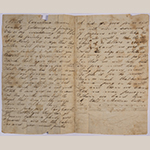

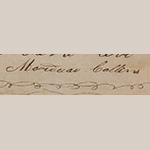

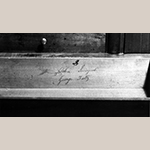

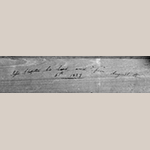

Henry Rupert was unquestionably a woodworker and a colleague named “Mordeka” was working with him. A second very important surviving letter, written on 30 January 1803, clarifies beyond any doubt that the “Mordeka” referred to in Rupert’s letter is seventeen-year-old Mordecai Collins the cabinetmaker. In that 1803 letter, Collins himself wrote a light-hearted, spirited retort to Solomon Henkel urging him to come on down and join them “in the woods,” if he wasn’t too much of a “Town Jockey,” where there was ample to eat, including “Possum baken [bacon] a plenty and Squarel [squirrel] too and seed tick baken” (Figure 30); the first delicacy is clearly a humorous allusion to the family’s new rustic address in “Opossumtown.” Collins signed the letter in scrawling letters, “Mordecai Collins” (Figure 31), and on the outside of his youthful missive challenged Solomon Henkel to “send and answer to match this”.[44]

Two additional letters suggest the type of woodworking Rupert, and presumably Collins, performed in Piedmont North Carolina. On 1 January 1803, Rupert wrote to Solomon Henkel, “Since we have been in Carolina, I think there is enough work for cabinetmakers. I would appreciate it if you could send me a good journeyman to arrange the work.”[45] On 17 February 1803, Rupert wrote one final surviving letter requesting again that Henkel send him helpers:

Send me now a good working man, I need one and you have enough of them loafing about, who are going hither and thither. Send me one and I will give them work, also such a good price as they are getting in town… . I undertook to build a house two stories high in brick, 30 x 20, and I think I can still get a framework house, if I want, also two stories high, if only I can get a good hand to work with me.”[46]

Although Rupert made furniture, he probably found house building in North Carolina to be more lucrative than cabinetmaking.

Henry Rupert stayed in Opossumtown only two and a half years, returning to New Market with his father-in-law, Rev. Henkel, in 1805.[47] No surviving furniture from the Davidson County area is signed by Rupert, nor is there any made in New Market; however, an early-nineteenth-century example of furniture with a strong New Market provenance might serve as a surrogate and provide an idea of what Rupert’s work might have resembled. A desk signed by New Market cabinetmaker James McCann (Figures 32 and 33) exhibits several of the characteristics found on later Swisegood school examples, including its French feet and cross-banded drawers with mitered corners and cockbeaded edges.[48] McCann’s desk might be representative of the furniture that Henry Rupert—and Mordecai Collins—were trained to make in New Market.[49] If so, then it was Rupert and Collins who most likely transferred the newer, neoclassical style popular in Virginia “into the woods” of Davidson County, where it then meshed with Jacob Clodfelter’s earlier baroque style.

It is unclear whether Collins had trained with Rupert or another Shenandoah County woodworker before the pair relocated to North Carolina. Collins may have apprenticed with Rupert, but he just as easily could have been one of those young woodworkers connected to Solomon Henkel that Rupert described as “loafing about… going hither and thither.” Although the identity of Mordecai Collins’s parents is lost to history, documentary evidence proves that he was born on 22 March 1785 “in Shenandoah County, Virginia” and that “before he attained to manhood’s estate he removed to Rowan County [Davidson], North Carolina.”[50]

Rupert and Collins probably worked together from 1802 until 1805, when Rupert returned to Virginia and Mordecai Collins stayed in Davidson County. At barely twenty years old, Collins possibly began to work on his own, but he much more likely opted to work as a journeyman in another shop for a few years, probably Jacob Clodfelter’s. Although there is no documentary evidence to place Collins in Jacob Clodfelter’s shop, the furniture signed by and/or attributed to Collins displays many of the baroque influences and construction techniques seen on Clodfelter’s furniture made at the turn of the nineteenth century.

The three surviving examples signed by Collins support the theory that Rupert and Collins were the ones to introduce neoclassical style into the region. The chest illustrated in Figure 34 is the first piece of signed Collins furniture to surface. On the back of the left drawer he scrawled his name in large red-crayon letters (Figure 35) and the signature matches very favorably with the one on the letter he sent to Solomon Henkel in 1803 (Fig. 31). With its French feet, complex light- and dark-wood inlaid stringing outlining the case bottom, barber-pole inlay outlining the scratch-beaded drawer fronts (Figure 36), and light-wood inverted teardrop keyhole surrounds, this chest is neoclassical in every respect.

Two additional characteristics seen on the chest in Fig. 34 that are found on other chests from the Swisegood school group are a top with a molded front edge and molded side battens attached with two wide through-tenons (Figure 37) and finely-made front dovetails exposed on each side of the chest rather than in front (Figure 38). Interestingly, the dovetails exposed on the back of this chest are wide, wedged examples (Figure 39) and some of the secondary wood is walnut—two features that appear on cupboards coming out of Jacob Clodfelter’s shop and support the possibility that Collins worked as a journeyman with Clodfelter.

Two unusual aspects of this chest are:

• The chest has French feet—almost all of the chests from the Swisegood school have simple applied bracket feet

• The French feet on this chest were not created by employing an inserted wedge typically found on other Swisegood school furniture with French feet (to be discussed below with the desk illustrated in Fig. 40).

This chest was once owned by the Spurgeon family who lived in northeastern Davidson County and who will be discussed in greater detail within the context of a John Swisegood corner cupboard (Fig. 83).

The second signed piece by Collins to surface is a desk (Figure 40) that stylistically is also fully neoclassical and is reminiscent of the signed McCann desk from New Market (Fig. 32 and Fig. 33). Once again the signature, located on the second drawer blade (Figures 41 and 42), is quite similar to the one Collins penned on his letter to Solomon Henkel (Fig. 31). The desk exhibits sophisticated drawer fronts with mitered figured walnut cross banding highlighted by inlaid complex stringing and cockbeading, and the drawer dovetails are much finer than those on the early Jacob Clodfelter drawers.

Perhaps most significant on this desk is what may be the earliest use of an inserted wedge to form a French foot on a Swisegood school piece of furniture (Figure 43). In this technique the foot is sawn in from below about three inches near the outer edge and then a wedge is inserted causing the foot’s profile to have a slight kick to the outside (Figures 44 and 45). The kick becomes more noticeable when a square pad is applied underneath. Every French foot on Swisegood school examples employs an identical pattern for the inner foot profile (from the base of the foot inward and upward to the respond).

Collins applied much narrower barber-pole inlay on the edges of this desk than that found on the drawer fronts of his signed chest (Fig. 34), but the inverted teardrop keyhole surrounds are very similar. The fallboard has a lipped edge and is decorated with an inlaid band (Figure 46). Also typical of desks in the Swisegood school are document drawers with shaped fronts reminiscent of book spines. Atypical of other desks in the group, this example has three upper pigeonholes on each side of the document drawers, but the undecorated small drawers behind the prospect door are typical (Figures 47 and 48). The original owner of the desk is unknown, but its regional history is strong. Writing on one of the small drawers indicates that in 1865 the desk was in the home of northern Davidson County blacksmith James L. Smith (1809–1902).[51]

The third example of signed Collins furniture to surface is a chest of drawers (Figure 49) with an even stronger family history than the desk. According to the last family member to own the chest of drawers, it descended directly from John Sink (1778–1833).[52] Although the location of John Sink’s grave is unknown, his son Adam Sink (1803–1887) was buried in the graveyard of Pilgrim Church, one of Rev. Henkel’s congregations.[53]

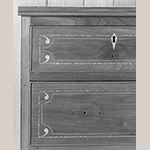

This chest of drawers has all the same characteristics found on the Mordecai Collins desk (Fig. 40), with a few notable distinctions. The drawer-front cross banding is figured cherry instead of walnut, but like the walnut banding on the desk in Fig. 40, the corners have been mitered. This piece also has comma-shaped light-wood inlay (Figure 50) traditionally associated with the Swisegood school (the same shape also found on several of the pierced gravestones; see Figs. 5, 7, 11, 13, 15 and 18). Its original oval pulls are identical to those found on other examples in the school that retain their original hardware (Figure 51). A construction technique found here and used on almost all of the chests of drawers in the school is a top of two solid layers screwed together from the bottom up (Figure 52).

Although no cupboards signed by Collins are known, the survival of a corner cupboard from his estate—and presumably made by him—suggests that his cupboards were slightly more refined, neoclassical versions of the earlier Jacob Clodfelter baroque example (Fig. 4). MESDA has not been able to examine the corner cupboard from Collins’s estate, and the only images of it are poor, but certain characteristics are discernible from the photos (Figure 53). Both the cornice and feet of the Collins cupboard appear to have been greatly altered, but the remaining central part exhibits two arched cupboard doors, flanking pilasters with fluted elongated “mushroom-shaped” caps, rope-twist inserts on the upper case edges, and a fluted applied molding above the drawer.

Perhaps the most similar intact Davidson County example examined by MESDA is the cupboard illustrated in Figure 54. It has delicate urn-shaped finials, two graceful arched doors flanked by pilasters with mushroom-shaped caps, fluted applied molding above the drawer, a scratch-beaded drawer front, and two lower doors with flat panels and lunetted corners. This is a more refined version of the earlier Jacob Clodfleter corner cupboard—one that has been influenced by a maker who was familiar with the neoclassical styles being made in New Market, Virginia. Yet this cupboard also has wedged drawer dovetails and wrought nail construction, suggesting it might have come out of a shop in which both Jacob Clodfelter and Mordecai Collins worked.

Even more illustrative of this meshing of baroque and neoclassical styles is the cupboard illustrated in Figure 55. Although the cornice and feet of this cupboard have also been altered, it clearly exhibits the merging of the earlier mushroom-shaped caps atop pilasters with neoclassical inlaid vases, vines, flowers, and barber-pole inlay. Yet the maker used walnut as a secondary wood and wrought nails, again suggesting that this cupboard may have come from a shop in which both Mordecai Collins and Jacob Clodfelter worked.

Perhaps one of the reasons that Collins remained in North Carolina when Henry Rupert returned to New Market in 1805 is that he had met his future bride, Christina Byerley (1788–1860), daughter of David and Lucy Byerley.[54] The Byerleys were early members of Pilgrim Church—again one of Rev. Henkel’s churches—and many Byerleys, including Collins’s father-in-law, were buried there.[55] David Byerley’s gravestone (Figure 56) is reminiscent of that made by Joseph Clodfelter for Josiah Spurgeon (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8).

According to an Indiana family genealogist, Mordecai and Christina Collins’s first child, a boy named John, was born in 1808, so one may assume they married around 1807.[56] Collins did not, however, purchase the land on which they lived until 23 December 1809 when: “John Scott [sold] to Mordecai Collins for $200, 103 ½ A on both sides of Reedy Branch of Brushy Fork of Abbots Crk.”[57] One of the witnesses for this sale was John Delap, the future father-in-law of John Swisegood. Almost a year later, on 6 November 1810, “John Swisegood Orphan of Philip Swisegood [was] Bound to Mordica [sic] Collins to learn the cabinet and joiners trade.”[58] In that same year, the Federal Census for Rowan County indicated that Collins owned one enslaved individual. What role the single slave played in the Collins household or shop can only be surmised.[59]

Mordecai Collins’s life story mirrored that of many of his contemporaries in that he trekked down the Great Wagon Road to Piedmont North Carolina and then, eventually, moved to the Midwest for even greater opportunity. He heeded the siren song of America’s heartland in the summer of 1816 when he left North Carolina after calling it home for over thirteen years. On 9 May he purchased 170 acres in New Albany, Floyd County, Indiana.[60] In August of that year he sold his land on the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek to William Ledford and never returned to North Carolina.[61]

In his new home he was one of the earliest settlers in the area of Galena, Indiana, was a founder of St. John’s Lutheran Church, took part in planning the New Albany and Vincennes Turnpike, and by 1860 owned $5000 worth of real estate.[62] The corner cupboard from his estate (Fig. 53) suggests that he crafted furniture while in Indiana, but in the 1850 and 1860 Federal Census records he was identified as a farmer. Collins died on 25 July 1864, and a week later his obituary appeared in the New Albany Daily Ledger, where he was described thus:

Capt. Collins was one among the few early settlers yet remaining, and his death will be lamented by a large circle of relatives and friends. His descendants are numerous and all occupy respectable positions in society. During his long residence in Floyd county he enjoyed in an eminent degree the confidence of his fellow citizens, and was the recipient of many important offices at their hands.[63]

Like Jacob Clodfelter’s, Mordecai Collins’s life appears to have been well lived, and his impressive grave marker (Figure 57) in St. John’s Pentecostal Church Graveyard near New Albany, Indiana, reflects the esteemed position he held in the community.[64]

John Swisegood Continues the Tradition

When Mordecai Collins moved from North Carolina to Indiana he left behind John Swisegood, his then twenty-year-old apprentice, to continue creating neoclassically inspired furniture for the rural residents of northern Davidson County.[65] Swisegood had grown up about fifteen miles southwest of the Bethany Church area, on Potts Creek, near Sandy Creek Lutheran Church (now called St. Luke’s Lutheran Church; see Fig. 10), another of Rev. Henkel’s congregations.[66] John Swisegood’s uncle, Adam Swisegood, was a founding member of Sandy Creek Lutheran Church and was acquainted with Rev. Henkel.[67] In 1811, while on a return journey to Davidson County, Rev. Henkel recorded in his journal, “This evening by candlelight I preached in the home of Adam Swicegood [sic] at his request, as he hoped that the preaching of the Gospel might influence others as it had influenced Him.”[68]

John Swisegood’s father Phillip Swisegood, a stonemason, died before 1800, and his mother Eva Helmstettler Swisegood was left to provide for seven young children. As a result, in 1804 John Swisegood was put under the guardianship of his uncle Christian Helmstettler.[69] Eva Swisegood remarried, to John Lewy, but he died in 1807, leaving her still in a precarious financial situation.[70] Thus, in 1810, when John Swisegood was fourteen years old, he was sent to the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek and apprenticed to Mordecai Collins “to learn the Cabinet and Joiner’s trade.”[71] Perhaps the mutual friendship between Rev. Henkel and both Mordecai Collins and Adam Swicegood played some role in John’s placement with Collins.

John Swisegood was an apt pupil. After Collins left in 1816, when Swisegood was only twenty years old, he was already creating superb neoclassical furniture. The earliest signed and dated example by Swisegood is an 1817 desk (illustrated in Fig. 58) that combines all the hallmarks of the Swisegood school vocabulary. In December 1818 Swisegood married Elizabeth “Betsy” Delap, whose father John Delap had witnessed Mordecai Collins’s deed to the only piece of property he ever purchased in Davidson County.[72] Ten years after he had been apprenticed to Collins, Swisegood took his own cabinetmaking apprentice, Jonathan Long, on 18 August 1820.[73] Long must have been performing basic shop duties before that because another desk signed by Swisegood and dated five months earlier, 26 March 1820 (illustrated in Fig. 63), has Long’s name scrawled on a backboard in red pencil.

During the next twenty-five years, John Swisegood appears to have been a good public citizen and neighbor, acting as a witness to wills, deeds, and bills of sale; serving as a juror; administering a neighbor’s estate; overseeing the maintenance of a road; and overseeing a company acting as a patrol. This last responsibility appears to have earned him the appellation of “Capt. John Swisegood” by 1836.[74] Also during this period he was accumulating property along the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek.[75] His father-in-law John Delap died in 1839, and in his will he had bequeathed $100 to John Swisegood and Betsy Delap Swisegood.[76] John Delap’s estate sale took place on 30 April 1840, and the items sold suggest that along with operating a still, Delap was at least a part-time woodworker himself. Sold were 4,710 shingles, 320 wagon spokes, 660 pieces of cooper’s wood, one lot of cooper’s tools, and wagon timber. The only item Swisegood purchased, however, was “a quantity of books and several small articles.” His one-time apprentice, Jonathan Long, purchased more items, including a bull, still, gauging rod, and a lot of scantling.[77]

Also in 1840, the Federal Census for Davidson County noted that Swisegood owned one young male slave, age 10 to 23. There is no indication that this enslaved individual worked in Swisegood’s cabinetmaking shop. In fact, the census recorded that all males in the Swisegood household who were old enough to work were “employed in agriculture.”

Evidence proving John Swisegood worked as a carpenter and cabinetmaker throughout his time in North Carolina is plentiful. Written in ink on a secret interior desk drawer of the earliest piece of furniture signed by him (Figure 58) is the following inscription: “I John Swisegood / his hand and pen this / 8 of March in the year 1817” (Figure 59).[78] Even though a twenty-one-year-old Swisegood would have only just completed his apprenticeship in 1817, this desk illustrates that he had mastered Mordecai Collins’s most sophisticated neoclassical style and construction techniques.

The desk has wedged French feet with applied pads and four graduated case drawers, each decorated with cross banding of figured walnut that is outlined with complex stringing and accented with light-wood, comma-shaped decoration (Figure 60). Unlike the Collins cross banding, however, Swisegood’s is butt joined in the corners, not mitered. The drawers have cockbeaded edges and inverted teardrop keyhole surrounds. The lip-molded fallboard is embellished with cherry cross-banding outlined with a triple string of inlay. A thin band of barber-pole inlay highlights the desk edges (Figure 61). The interior of this desk is more complex than that found on the signed Collins desk (Fig. 47) in that it is fully fitted with drawers that are decorated with stringing (Figure 62) and behind the prospect door are additional drawers, as well as three hidden drawers. The family history of the desk indicates that it was purchased at auction in northern Davidson County by William Clinard (1816–1901) on 11 April 1883, and descended to subsequent family owners.[79]

A second desk (Figure 63) signed and dated by John Swisegood is nearly identical in basic form to that of the previous desk (Fig. 58), but is embellished hardly at all—its only decorative elements are drawers with cockbeaded edges and light-wood inlaid inverted teardrop keyhole surrounds. The desk retains its original simple oval pulls, typical of those found on several other surviving John Swisegood pieces. Inscribed in ink on one of the interior drawers is, “John Swisegood March the 26 1820 / George Fultzs Desk / Jno.” (Figure 64) and “John Swisegood / George Fultz” (Figure 65) on another. The name “Jonathan Long” and an undecipherable date were written in red crayon on the inside of the backboards (not illustrated), and most certainly attest to Jonathan Long’s presence in the shop before his formal apprenticeship.[80] The desk was made for George Fultz (also spelled “Foltz” or “Volz”) (1798–1871), a Moravian gunsmith living in Salem, North Carolina.[81] Because Fultz would have been only twenty-two when this desk was made, he probably could not yet afford the more decorative features the Swisegood shop was capable of creating.

Although undated, one extant chest of drawers was signed by John Swisegood (Figure 66). He inscribed “Jno. Swisegood” in large red-crayon letters on the interior of the bottom board (Figure 67). This chest of drawers appears to be slightly later than either of the signed and dated desks because of the addition of a shaped skirt between the typical French feet, and a molded band rather than an inlaid one separating the feet from the base. The back side of the skirt is neatly chamfered and attached to the case with numerous glue blocks. This piece is decorated with barber-pole inlay that outlines the front and top edges of the case and the drawer fronts (Figure 68). One unusual aspect of this chest is that it has light-wood, lozenge-shaped keyhole surrounds rather than the more typical inverted teardrops.

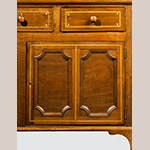

Several other examples of surviving furniture, though not signed, have strong family histories that make them almost assuredly by John Swisegood. The first example is a three-drawer side cupboard (Figure 69) strongly influenced by the style and construction of the earlier Clodfelter example in Fig. 26, yet it deviates from the earlier piece in subtle ways. While it has the upper and lower case joinery typical of the Swisegood school, and the original Prussian blue paint remains on the interior backboards (Figure 70), each lower door is divided into two flat panels by a stile and the main decorative element is very narrow light-wood stringing (Figure 71). Also, the central element of the three-piece cornice molding is coved instead of ogee (Figure 72).

As was the case with George Fultz’s desk (Fig. 63), this side cupboard was made for someone directly connected with the Moravian town of Salem. Its family history indicates that Samuel Schultz (1760–1825) commissioned it for his daughter Maria Agnes (1799–1878) upon her marriage to Johannes Reich (1795–1871) in Salem. The two were married on 19 November 1820.[82] Why Br. Samuel Shultz chose a Davidson County cabinetmaker to create this cupboard rather than a Salem cabinetmaker is unknown; regardless, it is notable that Swisegood made the cupboard in the same year, 1820, as he made a desk for another Moravian, George Fultz.

Another side cupboard, now in the MESDA collection (Figure 73), has a solid northern Davidson County provenance that strongly suggests it, too, was a product of John Swisegood’s shop. The cupboard’s upper and lower cases are connected with mortise-and-tenon joints (Figures 74 through 76) identical to those found on the side cupboards in Fig. 26 and Fig. 69. Unlike the relatively unadorned Shultz cupboard (Fig. 69), it exhibits the full range of Swisegood’s decorative motifs. The doors are divided producing four flat panels, each with lunetted corners and outlined with shaped molding. The door panels are outlined with a three-part inlaid band. The cockbeaded drawer fronts are all decorated, two with the same three-part inlaid band used on the lower doors, that is then accented with comma-like inlay in the four corners. The central drawer is embellished with barber-pole and comma-like inlay, along with an inverted teardrop keyhole surround (Figure 77). Barber-pole inlay outlines the edges of the upper part of the cupboard, stepping up to create a line above the two glazed doors. The three-part cornice on this cupboard has an unusually deep coved central element (Figures 78 and 79).

The cupboard descended to Chrissie Jane Leonard (1849–1887), the daughter of David Henderson Leonard (1808–1866) and Susanna Sink Leonard (1815–1901).[83] It was probably made for Chrissie Jane Leonard’s mother Susanna Sink (1815–1901) and commissioned from John Swisegood by her parents John Sink (1778–1833) and Margaret Hedrick Sink (1782–1835) when their daughter married David Leonard in 1832.[84] The signed Mordecai Collins chest of drawers illustrated in Fig. 49 also descended in the same John Sink family to their son Adam Sink (1803–1887). There seems a precedent had been set for John Sink to commission furniture made in the Collins and Swisegood shops.

Three corner cupboards that have strong ownership histories link them directly to John Swisegood as well. The small cherry corner cupboard in Figure 80, first illustrated in Paul H. Burroughs’s 1931 Southern Antiques, is an example of Swisegood’s neatly made but less costly corner cupboards.[85] Its basic form is very like the earlier Jacob Clodfelter corner cupboard (Fig. 4), but this example is much more refined and neoclassical. It retains the simple applied bracket feet and rope-twist corner inserts, but the lower door has been divided into two flat panels with applied molding. The molding below the drawer is more complex, the drawer is cockbeaded, and the applied molding above the drawer is fluted (Figure 81).

The upper door is arched but without the tombstone shape on the Jacob Clodfelter example. The scrolled pediment is more delicate, the mitered applied fan-shaped plinth is reeded and relatively flat, and the rosettes and finials have cleaner lines (Figure 82). The original glass pulls date this cupboard after circa 1835. A 1928 letter written by the cupboard’s then owner, eighty-two-year-old Mrs. Mary A. Swisegood in High Point, North Carolina, strongly suggests that John Swisegood was the maker. She wrote, “I can remember my father bought it from Capt. John Swisegood and I was always under the impression that he made it though I couldn’t positively say.”[86] Mrs. Swisegood’s father was John Green, and in the 1840 Davidson County census John Swisegood and John Green were very close neighbors, thus solidifying the Swisegood attribution.[87]

A very similar but larger cupboard (Figure 83) has an equally strong history that supports John Swisegood as its maker. The cupboard has two arched upper doors instead of one and flanking applied pilasters. Because of the extra shelf width, the double beaded upper shelves have two concave sections on the front rather than one (Figure 84). Reflecting the slightly later date of the cupboard, the pilasters here are topped with flat, rectangular caps (Figure 85), rather than the earlier mushroom-shaped caps. In this instance the bases and caps mirror one another exactly. The cupboard also has original oval pulls (Figure 86).

This cupboard illustrates a construction technique found on all of the Swisegood school corner cupboards with arched doors: the door frames are joined with long mortise-and-tenon joints held together with four or more pegs (see Fig. 85 and Fig. 129). As late as 1980 this cupboard stood in the John Spurgeon House in northeast Davidson County and it had been in the house so long that both paint and wiring were routed around the cupboard. The house was built circa 1845 for John Spurgeon (1798–1881).[88] When his father Joseph Spurgeon (1770–1859) died in 1859, listed in his inventory were “2 cupboards & ware,” and three years later when his mother Christina died in 1862, listed in her inventory were “2 corner cupboards.”[89] [90] This corner cupboard was probably one of them. Joseph Sprugeon was the administrator of Levin Charles’s estate sale in 1833, and at that sale John Swisegood bought “75 feet of cherry plank,” so the two men were definitely acquainted.[91]

A third corner cupboard (Figure 87) associated with John Swisegood is one of the most decorated and whimsical of all the surviving corner cupboards in the entire group.[92] Although basically a standard flat-top example, it exhibits more varied inlaid decoration than any other extant Swisegood school corner cupboard. The bottom doors are flanked by light-wood inlay in an ellipse-and-diamond pattern, while the doors themselves are outlined with barber-pole inlay. The cupboard drawer is flanked by inlaid undulating vines and leaves topped with tiny tulips. The cockbeaded drawer is outlined with barber-pole inlay accented with the comma-shaped pattern, and then inside of that rectangle is another one with lunetted corners made of very thin stringing (Figure 88).

Above the drawer is a band of fluted molding that is mitered in the center front (Figure 89). Inside the typical applied pilasters are additional inlaid vines and leaves growing out of hearts and topped with tiny tulips (Figure 90). A unique characteristic of this piece is that the standard flat top is crowned with an applied scalloped element that terminates in the center in two tiny scrolls, under which a small crown-like piece has been applied (Figure 91). The scalloped element is attached with neatly chamfered applied glue blocks, similar to those used to attach the apron on the signed Swisegood chest of drawers illustrated in Fig. 66.

This highly decorated cupboard has a solid history of having been made for John Specker Jacob Sink (1788–1866) and his wife Magdalene Clodfelter Sink (1791–1870).[93] Magdalene was the daughter of John Clodfelter, one of Felix Clodfelter’s three sons discussed earlier.[94] John Specker Jacob Sink and his wife Magdalene lived in a log house built probably around 1830. It was located a few miles from Pilgrim Church and is no longer standing, but fortunately was photographed before it was dismantled (Figure 92). Perhaps the corner cupboard was made with a truncated scrolled pediment because the ceilings in their log house were low and would not accommodate a fully scrolled example.

John Swisegood made many pieces of furniture—all neatly constructed, some simple and some fanciful—before he left Davidson County in 1846. Once he migrated to Schuyler County, Illinois, however, he appears to have become a successful full-time farmer. He is identified in the 1850 Federal Census as a farmer in Schulyer County with real estate valued at $4000 and in the 1860 Federal Census as a farmer with both a real and personal estate valued at $3700. John Swisegood died on 16 May 1874 and was buried at the Round Prairie Cemetery (Figure 93).[95]

Jonathan Long Makes His Mark

John Swisegood’s apprentice Jonathan Long was born on 7 July 1803, to Barnet Long and Catherine Livengood Long.[96] Nothing more is known of his life before he was “bound to John Swicegood to learn the cabinetmaker’s trade” on 18 August 1820.[97] As noted earlier, Long’s signature on George Fultz’s desk (Fig. 63), dated 26 March 1820, suggests the seventeen-year-old apprentice was part of John Swisegood’s workforce at least five months prior to the official apprenticeship bond.

On 8 April 1825, Jonathan Long married Mary “Polly” Clodfelter, daughter of Peter Clodfelter, one of Felix Clodfelter’s three sons discussed earlier, and Mary Amelia “Mealy” Waggoner Clodfelter.[98] The connections between the Long, Clodfelter, and Swisegood families were intricate and layered. Jonathan Long’s mother-in-law, Amelia Clodfelter, had a sister who was the first wife of John Delap Sr., which would make Delap simultaneously the father-in-law of John Swisegood and the brother-in-law of Jonathan Long![99] The complexity continued when Jonathan Long was paid $5.00 in 1826 by the estate of John Clodfelter, his wife’s uncle, presumably for a coffin.[100]

In 1827 Jonathan Long purchased his first of many pieces of property in Davidson County; it was a parcel on Farmer’s Creek, just west of the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek.[101] This is probably the region where he and Polly raised their family. The 1830 Federal Census indicated that Long was in his own Davidson County household with his wife and two young children. Presumably by that time the twenty-seven-year-old had opened his own shop, because shortly afterward, in 1832, Long signed and dated a chest of drawers (see Fig. 103). Like his teacher, John Swisegood, Jonathan Long appears to have been a good public citizen and neighbor, acting as a road overseer, serving on juries, witnessing deeds, and hosting neighborhood shooting matches.[102]

Jonathan Long’s accounts with Davidson County blacksmith James L. Smith support the theory that he was involved in both farming and carpentry/cabinetmaking from at least 1836 until his death. Most of his entries in Smith’s account book pertain to Smith making and repairing farming implements for Long, but several pertain to woodworking, such as Smith’s “making a gouge,” “working on a plane bit,” “making a screw driver,” “making a gouge out of a shovel,” “[selling] two dozen screws,” and “making nails.”[103] In the 1840 Federal Census, two of the ten people living in Jonathan Long’s household were engaged in “Agriculture,” while two were engaged in “Manufacture and Trade.”

When Long’s father-in-law Peter Clodfelter died in 1842, “Mary [Polly] the wife of Jonathan Long” was bequeathed $400 plus “beds and furniture.”[104] Long was paid for making coffins in 1843 for Valentine Harmon and in 1847 for George Haines.[105] The 1850 Federal Census indicated that Jonathan Long owned real estate valued at $800. In 1854, Jonathan and his brother Solomon, a documented gun stocker, were the administrators of their brother Felix’s estate. Felix Long’s inventory proves that he, too, was a longrifle maker; it was chock-full of rifle-making materials, including maple planks, German silver, triggers, gunsmith lumber, gun stocks, boring and dressing rods, and brass.[106]

As late as 1855 Jonathan Long was still making furniture, for in that year he paid blacksmith James L. Smith with “one table—$4.00.”[107] In his will dated 1858, Long left his wife Mary all his personal estate, “except my carpenter tools, all the walnut plank that may be on hand,” and a few other items that were to be sold at public auction to pay his debts.[108] He appears never to have owned slaves. Jonathan Long died on 16 March 1858 and was buried in the graveyard of what is today Midway United Methodist Church in northern Davidson County (Figure 94).[109] Other than Jacob Clodfelter, of the major cabinetmakers that comprise the Swisegood school, Long was the only one to remain in Davidson County until his death.

Jonathan Long’s basic furniture forms were very much like those of his master John Swisegood, but surviving examples signed by him or those with provenances related directly to the Long family can best be described as “neat and plain.” Long could not, or chose not to, embellish his furniture with scrolled pediments and fanciful inlay. Two practically identical corner cupboards illustrate this point. The flat-top cupboard illustrated in Figure 95 has Jonathan Long’s signature scrawled across the back of the angled and bent cupboard drawer. Its nod to decorative elements includes the rope-twist corner inserts, very thin inlaid stringing outlining the bottom and upper doors and drawer front, and a fluted and mitered applied molding above the drawer (Figure 96). The cupboard interior retains its original Prussian blue paint.

What is exceptional about this corner cupboard is its neatness. The back is just as neatly made as the front, with clean backboards, a nicely shaped back foot, and nails lined up orderly like soldiers (Figure 97). The bent drawer back has not broken through at the angles (Figures 98 and 99), as is sometimes the case, and the drawer dovetails are perfectly shaped (Figure 100). The cupboard has a family history of belonging to Alson Enochs (1850–1925) and his wife Sarah Ann Snyder Enochs (1850–1917), who lived just across the Davidson County line in Forsyth County.[110]

A second, almost identical, flat-top corner cupboard descended in the Jonathan Long family and thus can be attributed to him (Figure 101). This cupboard has the addition of applied pilasters on each side of the upper doors, with very simple, matching bases and caps. It descended from Jonathan Long to his son William, to Albert Long, to Effie Long Hiatt, who owned the cupboard in 1967.[111]

Three chests of drawers signed by Jonathan Long all have the same neat and plain simplicity of the corner cupboards. The chest in Figure 102 has the typical Swisegood school wedged French feet and four graduated drawers with inverted teardrop keyhole surrounds and cockbeaded drawers. It is signed “Jth. Long” on the back.[112] The chest of drawers illustrated in Figure 103 is a practically identical example and scribbled on the backboard with red crayon is “Jonithan 1832.” The third signed example (Figure 104) probably dates about ten years later; it has two top drawers instead of one and retains its original wooden knobs. It is signed under the base, “J. Long” in red crayon.

Perhaps the latest extant chest of drawers attributed to Jonathan Long is an unusual paneled-end example with turned feet (Figure 105). Because he worked in Davidson County until his death in 1858, Long appears to have been influenced, at least in this instance, by more fashionable national trends. The basic case form is similar to Long’s earlier chests of drawers, with cockbeaded drawers and light-wood inverted teardrop keyhole surrounds, but the paneled ends and turned feet give it a look more contemporary with prevailing mid-century styles. What makes this chest of drawers so appealing is its shaped apron with heart inlay (Figure 106) and applied engraved brass plaques bearing the initials “M” and “L” (Figure 107). Because Jonathan Long’s brothers Solomon and Felix were gunsmiths, they had access to metals, both silver and brass, as evidenced by Felix’s 1854 estate sale.[113]

Jonathan Long likely made this chest of drawers in 1840 for Mary Leonard Long (1818–1907), upon the occasion of her marriage to his brother Solomon Long (1812–1888). The “gun stocker” Felix Long, or possibly Solomon Long himself, probably engraved the brass plaques. Jonathan then applied them to the fashionable chest of drawers with the inlaid heart—a perfect addition to the household of his recently married brother and sister-in-law.

Employing au courant furniture styles such as turned legs and paneled ends seen on the chest of drawers in Fig. 105 was uncommon for Jonathan Long, as evidenced by the last extant example—in chronological terms—signed by him. Inscribed “J L 1856” on the underside of the lid, the very simple chest illustrated in Figure 108 has French feet, although not wedged, and was made only two years before Jonathan Long’s death. There is very little to differentiate this chest made in the mid-1850s from the “neat and plain” work coming out of Jonathan Long’s shop twenty years earlier.

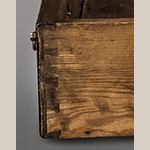

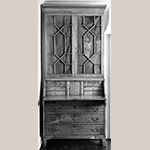

Although not traditionally associated with the Swisegood school, the desk and bookcase illustrated in Figure 109 was possibly made by Jonathan Long and could be considered part of the group. The primary wood of the desk and bookcase is highly figured maple, an unusual lumber choice for a Swisegood school cabinetmaker; however, the shape of the feet and the desk fenestration suggest its inclusion in the Swisegood school. The piece’s only provenance is from the mid-twentieth-century when it was purchased from a family living in a county adjacent to Davidson.[114] This is the only known example of a Swisegood school desk with a bookcase. Because Jonathan Long’s brothers used maple for their long rifles, and he would have had easy access to the lumber in their workshops, he is the most likely candidate to have made the desk and bookcase. Also, the highly figured wood is its only decoration, making the desk and bookcase fit well into the “neat and plain” style associated with Jonathan Long.

Jesse Clodfelter Joins the School

Jesse Clodfelter has been considered the final member of the Swisegood school of cabinetmakers, but his exact relationship to the group is not as clear-cut as that of the other members. No apprenticeship bond exists placing him with a master, but the style of Clodfelter’s furniture strongly argues that he trained with John Swisegood. Alternatively, Jesse Clodfelter was the grand-nephew of Jacob Clodfelter, the cabinetmaker who originated what has been recognized as the Swisegood style of corner and side cupboards (Fig. 4 and Fig. 26).[115] Because of that familial tie, Jacob Clodfelter himself may have apprenticed Jesse Clodfelter.[116]

Although three generations of Clodfelters had lived and farmed land along the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek—since 1763—it was sometime around the turn of the nineteenth century that Jesse Clodfelter’s father, John Clodfelter (1780–1845), moved a few miles northwest to the Moravian settlement of Friedberg (Figure 110). John Clodfelter had become a member of the Moravian church by 1803 because on 20 October 1803 he married Maria Magdalene Walk, another member of the Friedberg congregation.[117] Jesse was born to John and Magdalene Clodfelter nine months later, on 12 July 1804.[118] His sister, Hannah Elizabeth Clodfelter, was born in 1807, and the fraktur artist commonly known as the “Ehre Vater Artist” made a beautiful baptismal certificate for Hannah (Figure 111). One wonders if the “Ehre Vater Artist” made a fraktur for Jesse Clodfelter as well, but it either has not survived or its location remains unknown.

One of the advantages of being a member of the Friedberg Moravian community was that the Clodfelter children could be educated in the school there, and Jesse Clodfelter’s copybook, filled with his flourishing script and dated 1819, when he was about fifteen years old, has descended in his family.[119] Presumably shortly thereafter Jesse Clodfelter made the brief journey back to the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek where he either trained under John Swisegood alongside Jonathan Long (who was only one year older than Clodfelter) or was apprenticed to his great uncle, Jacob Clodfelter.

In 1822, when he was about eighteen years old and probably still fulfilling his apprenticeship, Jesse Clodfelter’s mother died and two years later his father remarried his deceased wife’s widowed sister, Hannah Walk Mock.[120] On 2 December 1828, when he was twenty-four years old, Jesse Clodfelter married a fellow Friedberg Moravian, Magdalena Hege.[121]

Just eight months after his marriage, Clodfelter made and signed his earliest extant piece of furniture, the most highly decorative of all his surviving chests of drawers (illustrated as Fig. 112). A month later Magdalena, his wife of nine months, died, perhaps as a result of childbirth.[122] In less than a year, Clodfelter married Maria Hartman “in her parents’ home” in the Friedberg community.[123] Shortly thereafter he purchased land on “the waters of Frys Creek” from his new father-in-law, Peter Hartman.[124] This was probably the location of Jesse Clodfelter’s shop—approximately ten miles from the shops of John Swisegood and Jonathan Long. In 1831 Clodfelter took his own apprentice, Levi Roads, but the young man must not have adapted to the carpentry business because the 1840 Federal Census identified Roads as working in the Davidson County mining industry.[125]

Catastrophe struck on the night of 28 December 1831 when Jesse Clodfelter’s father’s hat shop in Friedberg burned.[126] Perhaps because of their bad luck with the fire, John Clodfelter and his wife Hannah determined to move west, joining a group of “six or eight families… from Davidson County” on the long trek to Edwards County, Illinois, where they remained until their deaths.[127] Left behind, Jesse Clodfelter continued his woodworking business, and ten years later in the estate papers for his uncle Joseph Walk (brother to both Clodfelter’s mother and step-mother) Jesse was paid $20 for “2 bureaus for [Joseph’s daughters].”[128] The two bureaus were likely quite similar to the chests of drawers illustrated in Fig. 115 and Fig. 116.

Jesse Clodfelter continued woodworking for several more years. He made two coffins for Jacob Mock in 1842, signed and dated a corner cupboard in 1844 (illustrated in Fig. 118), signed and dated a chest in 1845 (illustrated in Fig. 121), and made a coffin for Susannah Hanes in 1846.[129] His father died 20 February 1845 and left Jesse Clodfelter and his brothers property in Edwards County, Illionois.[130] Only two months later, in April, Jesse’s second wife, Maria Hartman Clodfelter, died.[131] Six months afterwards he married a third time, to Anna Rosina Fischel in Friedberg.[132]

Jesse Clodfelter lived and worked in Davidson County until May 1848 when he sold his land near Friedberg and joined the rest of his family in Edwards County, Illinois.[133] Like Jonathan Long, he appears never to have owned slaves in North Carolina. The Federal Census for both 1850 and 1860 listed his occupation as a cabinetmaker. In the 1870 Federal Census he was identified as a farmer, probably too old to perform the demanding work of cabinetmaking. On 14 November 1870, Jesse Clodfelter died and was buried in the West Salem Moravian God’s Acre.[134] His estate included a “full set of carpenters tools & work bench” worth sixty dollars.[135]

In A History of Edwards County Illinois, the following was written about Jesse Clodfelter:

The Jesse Clodfelter family was unique in many ways. After his first wife [his second wife] died, in Winston Salem, NC, Jesse traveled with his five small children, by foot and a horse-drawn covered wagon, to join relatives at a small settlement in the Crooked Creek area north and west of where the Carl Mason farm now lies. There Jesse established the first “Ciphering and Penmanship School” in the area. The school, conducted in a crude log cabin, was eagerly attended by young and old, who were eager to learn to cipher and write legibly using their homemade goose-quill pens and birch bark pads; for paper was hard to get then.[136]

Ironically, it was Clodfelter’s ability with the written word and numbers, which he had learned in Friedberg, North Carolina, that brought him fame and respect in Illinois, not his furniture.

Jesse Clodfelter’s furniture is similar to that of other members of the Swisegood school, but many of his surviving pieces have later stylistic and construction characteristics. His most elaborately decorated piece is the earliest extant object made by him. The chest of drawers illustrated in Figure 112 has the same wedged French feet common to most in the group, but this chest has a shaped apron placed between the two front feet. The drawer configuration is two drawers over three, rather than the four graduated drawers popular earlier in the nineteenth century. All of the drawers are decorated with cockbeading and barber-pole inlay, inlaid comma-like accents, and line inlay with lunetted corners. The inlaid escutcheons are lozenge shaped rather than the more typical inverted teardrop style. The edges of the case are decorated with barber-pole inlay while the front of the top board is embellished with three rows of lightwood inlaid stringing (Figure 113). This chest of drawers is signed and dated with the following inscription: “Jesse Clodfelter his hand and pen August the / 5th 1829” (Figure 114). It was found in the Midwest, a fact that makes one wonder if it may have been in the covered wagon that took the Clodfelter family west in the 1830s.

A chest of drawers signed and dated 11 February 1842 (Figure 115) is much plainer with no inlay but is very similar in many other aspects to the example in Fig. 112. Its French feet are not wedged and are thus straight on the outer edges. The chest’s apron is shaped and its cockbeaded drawers have original glass pulls. Although not signed, a third and nearly identical chest of drawers (Figure 116) must be the work of Jesse Clodfelter as well. Its apron is shaped slightly differently, but otherwise the chests of drawers in Fig. 115 and Fig. 116 are identical. The chest of drawers in Fig. 116 is dated “December the 18th, 1840” (Figure 117) and the left top drawer is identified as such in exuberant, red-penciled letters and numbers that mimic the type of writing Clodfelter penned in his 1819 copybook.

The only corner cupboard signed and dated by Jesse Clodfelter (Figure 118) exhibits the same basic plan of earlier, more decorative Swisegood school cupboards, but the lower doors no longer have shaped moldings around their inner edges and the moldings above the drawer and the flanking pilasters are composed of fluted and reeded elements (Figure 119). The cornice molding concludes with a row of dentils, a style element not frequently found on Swisegood school examples (Figure 120). This corner cupboard is inscribed in red chalk on the left side of the back: “Jesse Clodfelter” and “July 31, 1844.” It descended in the Mock family that lived near Midway in Davidson County, perhaps the same family for whom he had made two coffins in 1842.

Clodfelter’s latest extant piece (Figure 121) is a simple chest signed and dated on the bottom in a flourishing hand: “January 7th 1845 / Jesse Clodfelter” (Figure 122). Like Jonathan Long, Jesse Clodfelter appears to have been conservative in his style choices and adoption of new fashions. The furniture made later in his life is very similar to the pieces made when he was a much younger man.

Collaboration Takes Place

Because members of the Swisegood school worked together at times, some furniture certainly represents the work of more than one hand. One example (Fig. 63) even has the signatures of more than one maker. Various collaborations of these northern Davidson County woodworkers were inevitable due to their regional proximity, family connections, and overlapping working dates—Jacob Clodfelter (working ca. 1790–ca. 1825), Henry Rupert (working 1802–1805), Mordecai Collins (working 1803–1816), John Swisegood (working 1810–1846), Jonathan Long (working 1820–1858), and Jesse Clodfelter (working ca. 1820–1848).

Such partnering extended to house building as well. Perhaps the most ambitious project undertaken in a collaborative effort was the decorative woodwork of Dr. William Dobson’s house (Figure 123), built from 1828 to 1829.[137] At two stories high, five bays wide, and two rooms deep, with an impressive pedimented porch supported by beaver-sawn columns, it must have been one of the costliest frame houses built in the region. When it was dismantled in 1982, the signatures “Jonathan Long” and “John S.” (for John Swisegood) were found on the interior woodwork.[138]

Although many men probably worked on Dr. Dobson’s mansion house during the years it was being constructed, numerous similarities between furniture created by John Swisegood and Jonathan Long and woodwork in the Dobson house are very apparent. The wide front door is divided into six flat panels (Figure 124), all with applied lunetted corners (Figure 125), much like those on many Swisegood school cupboards, and above it is a fanlight reminiscent of arched doors on corner cupboards. The parlor fireplace (Figure 126) has flanking pilasters decorated with carved rosettes very similar to those on the scrolled pediments of the group’s corner cupboards. Two rows of the mantel moldings are reeded and mitered bands, similar to those found above the drawers on several corner cupboards. Applied pilasters similar to those flanking corner cupboard upper doors flank the windows in two rooms (Figure 127). The technique of connecting separate parts of the staircase handrail with long mortise-and-tenon joints that are then pegged (Figure 128) is also found joining the arched doors of corner cupboards (Figure 129).

Dr. Dobson died soon after the house was completed, and listed in his 1830 estate inventory were several expensive pieces of furniture, including a desk and bookcase valued at $22.00 and a “bureau and bookcase” valued at $14.25.[139] John Swisegood and/or Jonathan Long almost certainly made Dr. Dobson’s furniture as well.

Conclusion

North Carolina’s Swisegood school of cabinetmaking spanned at least seventy years, from approximately 1785, when Jacob Clodfelter was old enough to begin woodworking, to 1858, when Jonathan Long died in Davidson County. It included at least six craftsmen, and probably more. Over one hundred pieces from the group have survived, attesting to the popularity of its style, the productivity of the makers, and the appreciation of owners who have passed them down through families as treasured heirlooms.

Swisegood school furniture furnished log and high-style houses, influenced architectural interiors, and is closely related to regional gravestone designs. Examples of the group were published as early as 1931. Historians and collectors saw nearly a century ago that the furniture was worthy of recognition, and it continues to be highly prized today.

Perhaps most importantly, the story of the Swisegood school of cabinetmakers is representative of thousands of similar artisan stories that, when combined, embody the narrative of early America’s development. The Clodfelter family left Europe seeking opportunity in a new and unfamiliar country. That journey brought them to Pennsylvania and subsequently down the Great Wagon Road into a wooded Piedmont North Carolina landscape ripe for settlement. Along the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek, their very successful family mingled with other families—Henkels, Ruperts, Collinses, Byerleys, Swisegoods, Delaps, Waggoners, and Longs—who had made similar journeys with corresponding hopes and aspirations.

As hard-working members of a new society, these northern Davidson County craftsmen lived difficult but productive lives that, in some cases, enabled them to carry their dreams even further afield, into the western territories of Illinois and Indiana. Persistence brought success, and ultimately all members of the Swisegood school died as admired and well-respected citizens. Taken as a whole, this group of cabinetmakers possessed the requisite qualities that helped create a new nation—natural talent, drive, a belief in opportunity, and the constant desire to make their families’ lives better than their own. That important American story is embedded in every piece of furniture they ever produced.

June Lucas is Director of Research at MESDA. She can be reached at [email protected].

[1] Davidson County was formed from Rowan County in 1822; to prevent confusion, hereafter the geographic area discussed in this article will be referred to as Davidson County, North Carolina.

[2] Frank L. Horton and Carolyn J. Weekley, The Swisegood School of Cabinetmaking (Winston-Salem, NC: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1973).

[3] Ibid, Introductory text.

[4] Ibid, Catalog Entry 1.

[5] Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “A Study of Baroque-and Gothic-style Gravestones in Davidson County, North Carolina,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Vol. 3, No. 2 (November 1977), 43–46 (available online: https://archive.org/stream/journalofearlyso32muse#page/42/mode/2up [accessed 4 February 2016]).

[6] M. Ruth Little, Stick & Stones: Three Centuries of North Carolina Gravemarkers (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1998), 151.

[7] Ibid, 157.

[8] Ibid, 153.

[9] Charles H. Glatfelter, The Early Glattfelder Family in America: An Overview (York, PA: Casper Glattfelder Association of America, 1993) (available online: http://www.glattfelder.org/images/Docs/Reports/EarlyGlattfelderOverview1.pdf [accessed 4 February 2016]).

[10] Ibid, 13; for documentation of facts and quotations about the Clodfelter family in Pennsylvania cited in this paragraph.

[11] F. J. C. Hertzog, Records, Christ Evangelical Lutheran Church, City of York, York County, Pennsylvania, 1733-1800 (manuscript, 1919–1921), Collections of the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania, No. Y 1L – 5L, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA; cited from York County, Pennsylvania, 1733-1800: Christ Evangelical Lutheran Church, Ancestry.com (available online: http://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=4936 [accessed 4 February 2016]).

[12] Gravestone for Peter Clodfelter, Bethany United Church of Christ Graveyard, Midway, Davidson Co., NC (available online: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=Clodfelter&GSfn=Peter&GSby=1763&GSbyrel=in&GSdy=1843&GSdyrel=in&GSst=29&GScnty=1679&GScntry=4&GSob=n&GRid=8850410&df=all& [accessed 4 February 2016]); Glatfelter, The Early Glattfelder Family in America, 13.

[13] Ibid, 8.

[14] Jo White Linn, Abstracts of the Deeds of Rowan County, North Carolina, 1753–1785, Vols. 1–10 (Salisbury, NC: J.W. Linn, 1983), 63.

[15] Ibid, 98,

[16] Gravestone for Jacob Clodfelter, Bethany United Church of Christ Graveyard, Midway, Davidson Co., NC (available online: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=8870483 [accessed 4 February 2016]).

[17] In 1790 Felix Clodfelter accumulated more land on the Brushy Fork of Abbotts Creek, this time purchased from Thomas Long (Jo White Linn, Abstracts of Deed Books 11-14 of Rowan County North Carolina 1786-1797 [Landis, NC: James W. Klutz, 1996], 62).

[18] Ibid, 96; James W. Klutz, Abstracts of Deed Books 20-24 of Rowan County North Carolina, 1807-1818 (Cary, NC: James W. Klutz, 1999), 138.

[19] “North Carolina Probate Records, 1735-1970,” FamilySearch, Rowan > Wills, 1797-1819, Vol. G > images 321–323 (pp. 306–308); county courthouses, North Carolina (online: https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-195-375240-1-46?cc=1867501 [accessed 4 February, 2016]).